Paper kingdoms 6: claire M. L. bourne

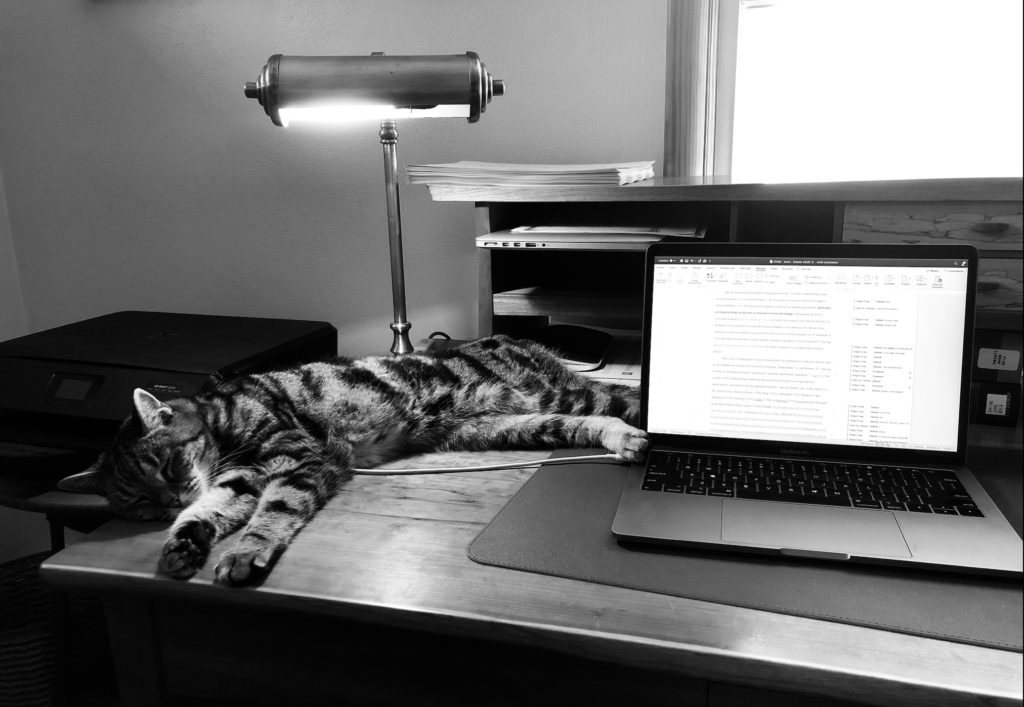

‘Wherever possible I’m looking for that loose, drafty mode of writing where my nerves about not getting things quite right melt away.’ – Claire Bourne’s writing desk

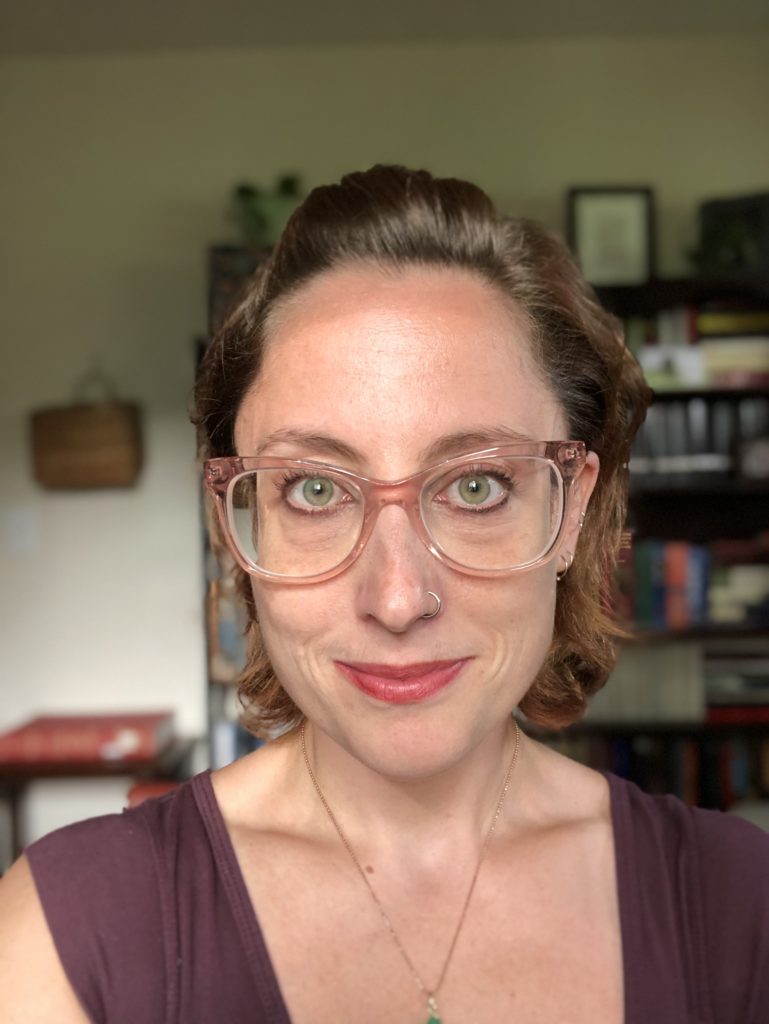

Claire M. L. Bourne is Assistant Professor of English at Penn State University in Pennsylvania, where she teaches courses on Shakespeare, early modern drama, the history of the book, theatre history, and textual editing. She also runs the website ‘Of Pilcrows’, which curates a rich list of digital resources for teaching and researching early modern literary culture. Her first monograph, Typographies of Performance in Early Modern England (OUP, 2020), is the only book-length study of playbook typography from this period.

Claire and I shared a graduate supervisor in Tiffany Stern, who first introduced us amid an excitable gathering that also included Adam G. Hooks and at which I knew my lack of any kind of book history tattoo to be a moral failing (both Adam and Claire have excellent examples). I remember our group pausing mid-chat to watch a huge red hot air balloon sidle past overhead. A year or two later, my friend Jakub and I bought Tiffany a balloon ride as thanks for her doctoral supervision; a gift that began in that moment of collective silence and craned necks.

When we first met I had read and loved Claire’s work in ELR and PBSA, but over the next few years I found more of her writing in various edited collections. Her work is always wonderfully lucid, pursuing the interpretive possibilities of the material without sacrificing precision. Like Adam Smyth, Claire is also at the centre of a wide and generative network of scholars interested in materiality, textual studies, and book history broadly conceived. To me, she seems a future leader of these fields, which is not to diminish her stature as it stands.

Claire and I spoke for around two hours in the middle of the summer quarantine period and as she was gearing up for a season of Milton talks. If you’ve found your way to this site then you’ve probably read Claire’s chapter in the Early Modern English Marginalia volume, which prompted Jason Scott-Warren to get in touch with her and for the pair subsequently to announce the discovery of John Milton’s copy of Shakespeare’s First Folio [watch one of their talks here]. We talk about this exciting discovery below, among other things. I’ve organised our conversation into five sections: first, (1.) Writing Habits, which includes thoughts on revising material and tricks to get started. Next is (2.) Thesis-to-Book, which contains some sharp thoughts on what makes a good academic book and how to avoid transforming your thesis into a perfect yet unreadable reference book. Then we spoke about (3.) Milton and Collaboration, before turning to strategies for coping with (4.) Early Career Academic Life, and a final brief foray into (5.) Editing, given that Claire is working on the Arden 4 edition of Henry the Sixth, Part 1.

My thanks to Claire for finding time to reflect on her working practices, for being open about the challenges and pleasures of early career academia, and for supplying the images of herself and her workspace that feature below.

(1.) Writing Habits

INTERVIEWER

Do you enjoy writing?

CLAIRE BOURNE

Sometimes. One of the things I’ve learned about my relationship to writing is that I have to listen to my intuition on a given day. I have tried hard to be someone who writes every day for a little bit. But it doesn’t work for me. I have some days where I feel the right energy, and other days when it’s not there. And on the days when it’s not there, I’ll read or take notes or do some freewriting by hand.

Writing is an embodied practice for me. So, for example, when I was revising my book, here’s something I did a lot when I was stuck on a sentence or a paragraph: I turned to a blank notebook page and would put everything away and just try to write from hand by memory without the encumbrance of former prose or other writing clutter around me. I found that to be an effective method for late-stage writing. But it has also been helpful in the early days of trying to articulate something new, which is where I feel I am now.

I also write in my head a lot before I put something on paper. When I’m walking or showering or working out, a formulation will come into my mind–a sentence or an idea–that feels like it is worth recording in a more permanent way.

INTERVIEWER

How do you capture those thoughts?

CLAIRE BOURNE

I sometimes type phrases or formulations into the notes function in my phone, if I’m walking. Or I jot them down in the ‘miscellaneous’ notebook I keep handy.

But if a thought or idea is firmly enough in my brain, I might stop short of writing it down. I love re-writing and revising. One strategy I’ve developed for enhancing that process is stopping at the end of the day just before I’ve finished writing through a thought or idea. Picking up that idea usually powers me for the first hour or two of the next day when I have caffeine flowing through my veins, and maybe I’ve done a workout and have those feel-good endorphins in my body. The risk of that, of course, is crashing, and the rest of the day could be useless.

INTERVIEWER

How long is a good productive spell of writing for you?

CLAIRE BOURNE

I would say if I can carve out two to three hours of concentrated writing time, I can produce quite a lot, whether words or ideas. But I’ve given up on consistent metrics for measuring success and productivity.

One piece of writing advice I have received—and would give—is to break down your goals into really small chunks. So a daily writing goal for me might be: I want to write through a close-reading of this particular passage. And that might produce four sentences, or it might produce three pages. I also typically never set out a whole day to write but instead designate smaller windows of time: break down a day into, say, two hours of writing in the morning and two hours in the afternoon. I would also say that, in general, I’m a maximalist writer when I draft.

INTERVIEWER

Meaning that if in doubt about something, you’ll include it.

CLAIRE BOURNE

Yes. Which is why re-writing tends to be so exhilarating for me. The way I describe it to my students is that revision is the process by which you reveal a big hunk of rock to be a gemstone. At first, it is admirable in its heft and weight but doesn’t look pretty. It is substantial but unwieldy. It is a rock that could be any ordinary rock. No one would know it had something precious inside unless you showed it to be there. The revision process is about making that rock lapidary: chipping away, shaping, polishing it, over and over again. If I write a thousand words, I can almost guarantee that what I’ll end up with is about 250 words. I would say that most of my writing that finds its way into print happens in revising.

INTERVIEWER

Where does the bulk of your intellectual labour sit within your writing process? Are you someone who thinks and plans intensively and then writes, or are you someone who thinks with your fingers, discovering things as you type?

CLAIRE BOURNE

I’m somewhere in the middle. My initial writing is baggy and procedural and full of thought process. It has a lot of stuff in brackets and marginal notes or loose footnotes. I don’t mean a note that says ‘cite this work here’, but a note that might say: ‘what about this thing?’ or ‘do I need to address this other thing?’. And it’s usually just beyond this stage of drafting when I’ll need to send it out to someone else to read. I need someone to mirror back my argument to me. Sometimes it’s a (not-so-)fun but also helpful game of telephone, where the gaps in my arguments become clear in a way that they weren’t before. These are always reciprocal relationships—I read their drafty writing in return!

In an ideal world, this would be a slow process, leaving ample time to let ideas and formulations marinate. But I always budget less time than I think I’m going to need to write. I’m constantly pressing right up against deadlines, writing in a kind of fever dream. As terrible as it can feel at the time (and really, truly, it’s not pleasant), I think that pressure actually helps me be less inhibited, at least in the drafting phase.

INTERVIEWER

Do you ever feel stuck or blocked with writing? If so how do you handle that?

CLAIRE BOURNE

Yes. I often have to trick myself to get into a rhythm. I have a few different strategies for that. One that has emerged organically over the last year is via informal exchanges with academic friends. I’m on a couple of group texts which function like writing accountability groups. Over the summer, one of those groups involved doing a three hour virtual writing session on a Tuesday and a three-hour session on a Thursday. (At the moment, there is less of a schedule but the accountability is still there.) We check in with one another at the beginning by writing what we’re thinking about or wanting to argue. That group chat has become a low-stakes place to articulate something of what I’m trying to write in miniature, and even though there’s an audience there I feel far less pressure there than if I were to try to put to paper what I wanted to say formally. Often, the ensuing exchange will help refine the idea or a colleague will suggest language that I’ve been stretching for and that I can later develop. These are starting points.

Another trick I use is to take a quotation I want to fight with or agree with and write around that, as a way in. Wherever possible I’m looking for ways in to that loose, drafty mode of writing where my nerves about not getting things quite right melt away.

INTERVIEWER

Do you start at the beginning of a piece of writing, or might you jump into the middle?

CLAIRE BOURNE

It depends. I always intend to start at the beginning of the piece but that early writing often ends up somewhere in the middle of the actual piece. I tend to write a loose articulation of the main argument as I conceptualise it when I start out, but that always changes. I usually find (unsurprisingly) that my clearest articulation of argument comes in the conclusion of my first draft. I then move that to the beginning. As I teach my students, a thesis is always a conclusion.

INTERVIEWER

Can you say any more about your process of revision?

CLAIRE BOURNE

In an ideal world, I’d be able to have time away from the draft, ideally a couple of weeks. But this rarely happens. I’m lucky if I end up with 48 hours. No matter what, I have to print my writing out. I can’t read from a screen–I can’t see things in a fresh manner. Printing out enables a more embodied process of revision. And I feel less pressure when I’m revising by hand, because I don’t feel the same need to get the perfect words as I do when I’m typing. So for me, printing out, revising by hand, and then coming back to the computer offers a two-fold process of revision that helps the work to get sharper and shinier.

‘I would say that most of my writing that eventually finds its way into print happens in the revising process’ – Claire M. L. Bourne

INTERVIEWER

What software do you use to write?

CLAIRE BOURNE

I’ll sometimes use Scrivener for drafting. I find Scrivener to be especially helpful in rare book libraries, because it allows me to have many separate documents within a larger document. I like that because I can write a few sentences about the various items I’m looking at in these different documents. If I don’t write down what I observe in full sentences as I’m observing it, I’ll lose it.

For more formal drafts, I just use Word, because the footnotes of Scrivener don’t transfer into Word very well. And Word has this ‘focus’ feature which I use a lot to eliminate visual distraction.

(2.) Thesis-to-Book

INTERVIEWER

Your first book, Typographies of Performance in Early Modern England [OUP, 2020], recently came out. Congratulations! I understand that it evolved from your thesis. Could you talk about how the idea for the project emerged?

CLAIRE BOURNE

I was involved in journalism in college. One of the things I loved about working on the weekly newspaper was design: the layout for the paper; how to position images and articles, et cetera. And then taking the book history and bibliography class in Oxford during my M.St. helped me to realise that I could switch this part of my brain on again in the context of literary study. That’s what got me interested in the broad topic of how design teaches you to read, or manipulates the way you read. I began to think that if this level of influence and experiment is visible in a college newspaper circa 2004, then it must have been all the more powerful in the early days of print when those conventions hadn’t yet settled.

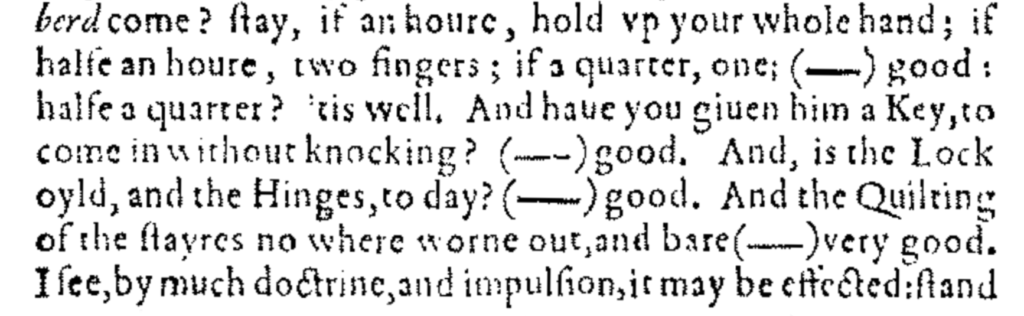

And in my academic reading during my PhD I kept finding that scholars and editors were dismissing the design of early modern playbooks as messy and awkward. So I wanted to see if I could recuperate that. As I was finishing my reading for my comprehensive exam, around two days before the exam, Zack Lesser passed me in the hallway and asked how it was going. And I said, ‘I’m almost there, I’m almost ready for this’. And he said something like, ‘But I just want to make sure you read [Ben Jonson’s play] Epicœne, okay? It’s a great play’. So I spent the two days before my exam reading Epicœne, which is full of these parenthetical dashes that Jonson calls ‘breaches’. I became completely fascinated by them! They instantiate something theatrical; not an interruption by speech but a sort of textual blank that signals action, particularly the kind of humoral action that Jonson loved to dramatise. So Zack was right, I did need to read that play. I don’t know if that was intuitive or how that came about, but he was right.

Ben Jonson’s typographical ‘breaches’ in Epicœne (1620). Image from EEBO of C4r of the 1620 edition.

INTERVIEWER

Could you talk about the process of moving from your thesis to your book, and the kinds of challenges that involved?

CLAIRE BOURNE

My dissertation itself was a series of Hail Marys. I found these interesting typographical arrangements in early modern playbooks and built my chapters around them as focused case studies, hoping that when I later had the chance to zoom out and contextualise them properly, they would, in fact, be doing these experimental things.

I finished the dissertation and felt happy with it, but was also very nervous about the next steps because you don’t know what’s an experiment till you know what’s a convention. I knew that what I actually needed to do was to survey two hundred years’ worth of playbooks to figure out if these typographical features were in fact experiments or if they reflected what was going on in the design of other playbooks of the time.

With a good deal of luck and also in large part due to some people who put a lot of faith in me as an early career scholar, I got a long-term fellowship at the Folger Shakespeare Library soon after finishing my PhD. So that gave me almost a whole year in which I could survey somewhere around 1,500 discrete copies of plays printed between 1500 and 1709. There were some gaps in my records, but I subsequently filled them in on other fellowships and research trips.

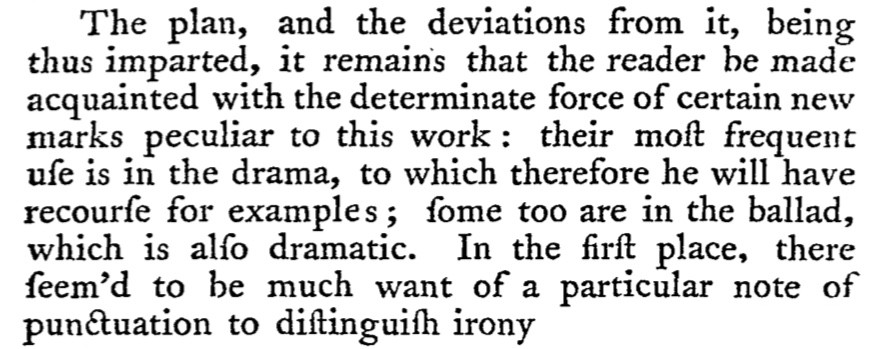

So basically what the book does is develop some of the arguments I was making in the dissertation by providing the context for those experiments. And it has an additional chapter: I broke the first chapter of the dissertation into two fully fledged chapters. The book also ends with new material about Edward Capell in the eighteenth century and the dismal failure of his edition of Shakespeare. Capell was very invested in design and typography, almost to a fault, and I finish with a discussion of him not understanding that effective design work is predicated on reader competency. Readers have to understand how to read a thing in order for it to be successful. For instance, the reason that pilcrows come to divide a play into units of dialogue in very earliest English playbooks is because readers already know how to read that symbol as ‘new unit of text’. But Capell does all these crazy things with symbols to encode tone and action, which do make sense when you think about them, but readers had to think too hard about them in order for them to make sense. So his edition failed.

Edward Capell’s introduction of ‘certain new marks’ of punctuation in his Prolusions (1760), used for his

experimental edition of Edward the Third. Image from ECCO, of p. v from the preface.

INTERVIEWER

Your thesis-to-book experience sounds relatively smooth. You added a chapter and you worked hard to establish the wider context. It sounds as though it went according to plan.

CLAIRE BOURNE

Yes, I think that’s fair. I know a lot of people end up with a dissertation where they have to re-conceptualise the project, and I would say that happened to me in local ways but not with the project as a whole. The dissertation was very much a draft of the book. The transition from the thesis to the book was smooth, but–and I have to stress this–that’s because I was afforded the time and the space to do the work I needed to do. I also had the essential support of librarians at the Folger and elsewhere. This book would not have been possible without their patience and guidance.

There’s another version of this book where I didn’t get a long-term fellowship at the Folger. It would have been a very different book, or it would have taken much longer to write. As it stands, the book has a historical scope and a depth of exposure to materials that the dissertation lacked.

INTERVIEWER

What advice would you now give yourself at the start of transforming your thesis into a book?

CLAIRE BOURNE

One of the things I really struggled with at the start of this process concerned my data. To keep track of my survey of playbook typography, I built a database to capture the typographical information of the playbooks that I looked at. So: does this play have black letter? Does it have scene divisions? What typeface does it use for speech prefixes? And so forth. So I have this data on all these playbooks. And I had a hard time figuring out quite what to do with that mass of information. For a while, I felt that the book needed to be comprehensive, and to cover everything that could ever be said about early modern playbook typography. Which would have made it a reference book. That was my crisis. And then, I can’t quite remember when it happened, there was a moment when I realised the best academic books in our field do this: they are proof of concept of a method, and not a comprehensive account of a thing. That is what I would tell the version of myself from five years ago.

INTERVIEWER

Can you say a little more about that?

CLAIRE BOURNE

The book has five chapters, and they all bring together some typographic feature that mediates an aspect of performance to make the performed play legible in print, which is to say, to readers. These features mean that you can pick the playbook up and read it and know that you are reading a play—and also, to some extent, how to read it. But I could have had five completely different chapters. For example, I have a whole bit about the typographic mediation of ‘asides’ that I could have included but, in the end, chose not to. I realised that the book is not just

‘I realised that the book is not just about the content; it’s also about offering a way of reading.’

about the content; it’s also about offering a way of reading. If someone can take that method and produce insights about other printed plays, the end result of my work is more powerful than the version of my book

which purports to be an all-encompassing reference work. I want to be a scholar who offers a method and is glad if others take it up. So the turning point in the project coincided with a period when I was thinking carefully about the kind of scholar I wanted to be in this profession.

Another thing I would tell myself five years ago would be to consider the audience for the book. One of the things we’re trained to do in grad school is to write to the expert; to the person who knows the most about your topic. So, in some senses, we end up writing to the most intense critique our work could ever receive. I realised that if you write in this way when you write a book, as if you are writing (in my case) to the most hardcore bibliographers out there, then you will get stuck. I’m not saying not to do the rigorous work. This is more a question of style.

Perhaps one way to think about it is as a movement from a defensive mode of writing to a pedagogical one. Realising that shift freed me up to write in a more limber way. When I got my reader reports back and I had a chance to revise, I tried to loosen things up. You have to let the writing breathe. It’s okay to take a breath and to repeat a point. It’s okay to be a bit more conversational as you write from a place of authority.

INTERVIEWER

You set that tone in your prose very early on your first page with your long, direct-address footnote.

CLAIRE BOURNE

One of the readers told me to take that out! No way.

INTERVIEWER

I really liked it. It read like an assertion of your presence and a decision about the kind of tone you wanted to set on that important first page.

Do you have any advice about how best to navigate the lengthy process of academic book production?

CLAIRE BOURNE

I had a good experience with Oxford UP. Ellie Collins there was fantastic. There were some issues with rendering some of the special characters (that is, symbols) in the book, so we went back and forth about that. I requested to see a second set of proofs, because I just wanted to make sure that the design work was perfect, given that it’s a book about book design. And I’m really glad that I did that because I did find some more errors. So, I’d encourage people going through this process to advocate for yourself and the work. Ask lots of questions. Request an extra set of proofs. Don’t settle if something doesn’t look right.

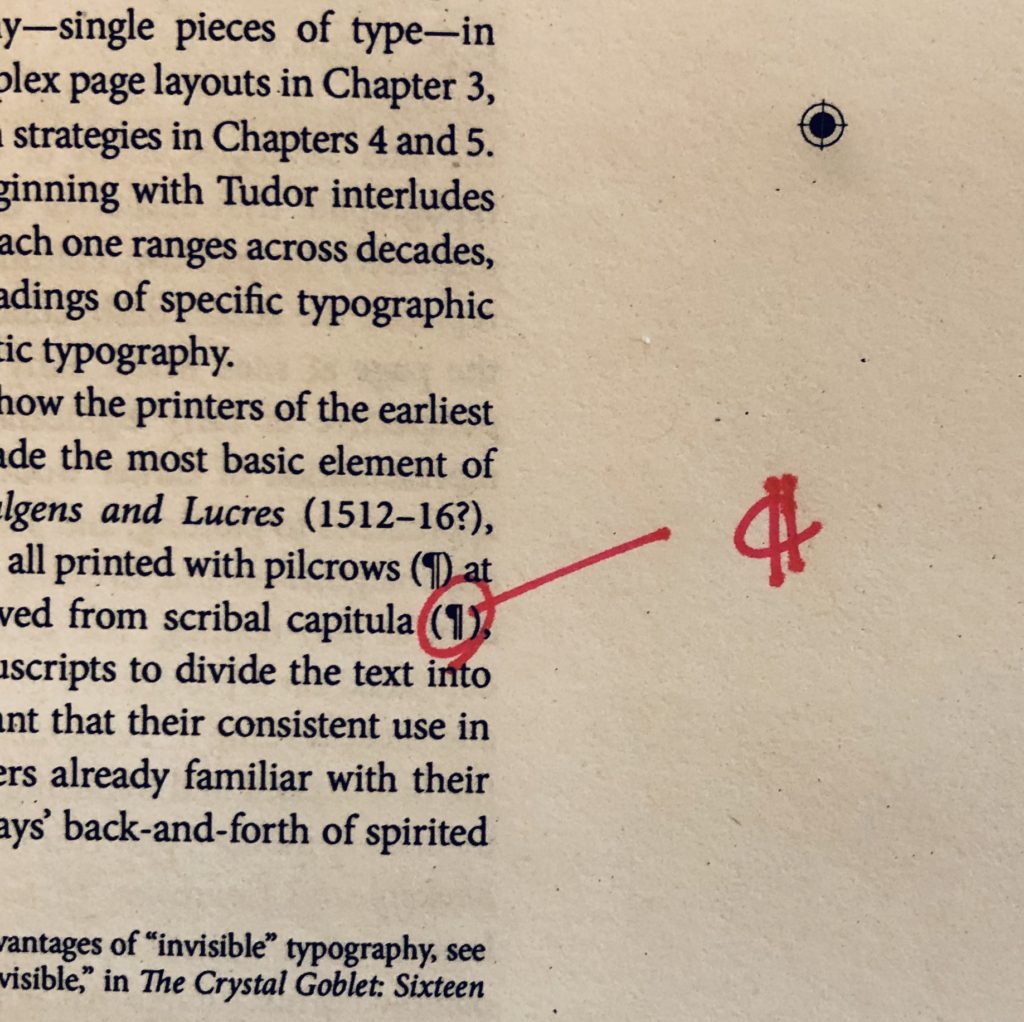

Proofing mark from Typographies of Performance

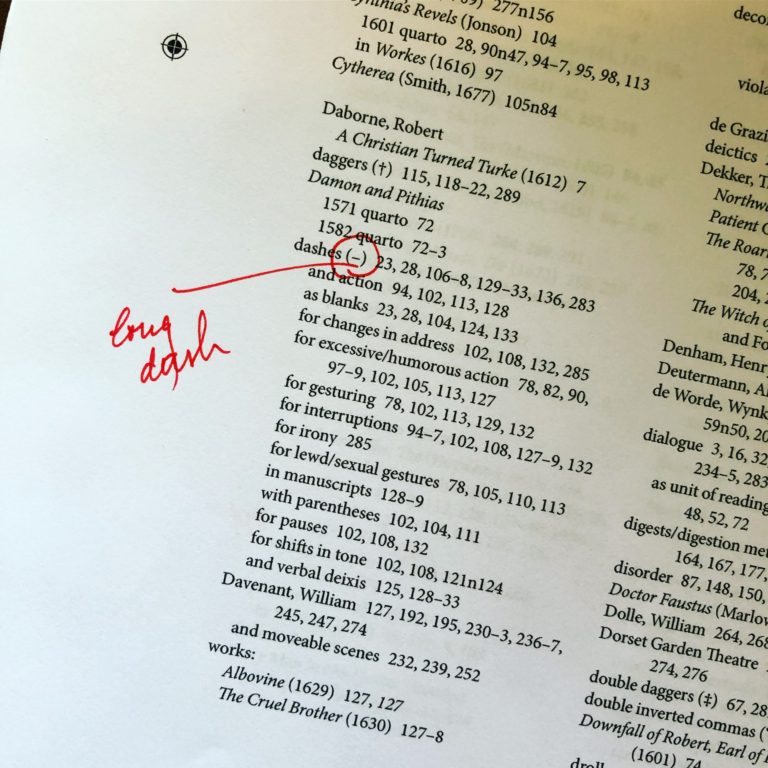

Perhaps the most heartening and unexpected aspect of the production side was the index. I really wanted to index the book myself, but the timing was so bad and I had another big thing I needed to write and submit. So I hired an indexer named Puck Fletcher. They have a graduate degree in Renaissance literature so they know the field really well. Puck read my book so carefully and produced this astonishing index. It is just amazing. When I received it I saw a new way to read my book. I didn’t expect to be so taken with it! It was a heart-stopping moment.

INTERVIEWER

Why was that so powerful?

CLAIRE BOURNE

I think because the index broke the book down in this new way. When you’re working on a chapter, you’re entrenched in a specific set of terms or personalities or objects. And they cohere in a certain way. And then in the index there’s an entirely different principle of organisation at stake, which is the alphabet rather than topic or chronology! And suddenly these pieces of your book are broken apart and sidle up against each other in strange ways, so that objects from one part of the book sit beside characters from another part. This new perspective felt exciting. I always knew that there was a lot of labour that went into this book, but seeing the index made me think: wow. There was that much labour. That realisation was tinged with a bit of nostalgia for the journey of writing it.

INTERVIEWER

Was part of it also that the index was the result of another person’s sensitive reading of your book? And perhaps Puck was the first person who produced something that reflects their experience of the whole work.

CLAIRE BOURNE

That was certainly a big part of it. And Puck is also someone who I’ve never met before and who only knows me through this thing I’ve written. So they owe me nothing, except a functional index. And what Puck produced goes so far beyond a functional index.

INTERVIEWER

You’re clear that the community of people with whom you felt able to share work had a large influence on your book. Could you talk about the importance of finding people with whom you can share work?

CLAIRE BOURNE

Imposter syndrome is a huge problem for all of us! I was really lucky to do my PhD at the University of Pennsylvania, where there was a relatively large and thriving cohort of pre-modern faculty and grad students. We all shared work through a departmental works-in-progress reading group. It was a fairly low-stakes environment to workshop less-than-polished writing and ideas. And we also had the History of Material Texts seminar every week, which meant that once a week I was in a community of interdisciplinary scholars who work with rare books in various capacities. It was within that setting that I made strong connections and grew my confidence.

I’ve recently been thinking about how to integrate collaborative work into my graduate teaching and how to mentor students towards that spirit of joint inquiry and making. One of the ways I tried doing that in my most recent graduate class was by having students edit a lesser-known play called A Wife for a Month for a digital edition of Beaumont and Fletcher’s plays that I’m working on with colleagues Penn State Libraries. Over the course of the semester, each student edited their own act of the play, but there were two people editing each act, which meant they could then talk to each other about their editorial decisions, especially when one or both of them reached an impasse. The editing assignment was far from perfect, but I hope it opened up time and space for students explore the value of talking to each other and working with each other on a shared pursuit.

My feeling is that we need to think more about working through, rather than on, something. What that means in practice, especially in the classroom but it also applies to research, is recognising that dwelling or struggling with ways of approaching a question or an object or a task can be far more useful than valuing only the outcome of that process. It’s always edifying to figure out something about a particular book, say, that John Milton is a former reader of the Shakespeare First Folio at the Free Library of Philadelphia. But actually, paying attention to the methods required to come to that conclusion makes it possible to read other otherwise inscrutable book objects and perhaps, for example, gain access to early readers or reading practices who are not as present as Milton is in the historical record. Same thing for editing. Attending to how we make editorial decisions makes us more astute readers of modern editions.

(3.) Milton and Collaboration

INTERVIEWER

Could you talk a little about how you and Jason Scott-Warren handled the collaborative nature of your discovery of Milton’s copy of Shakespeare’s First Folio?

CLAIRE BOURNE

One of the things I’ve been struck by in my training, through my PhD and professional life, is how we are conditioned to work as solitary beings. All of the structures of academia are set up to reward solitary achievement. All the PhD benchmarks (exams, dissertation, &c) are performed and rewarded as products of isolated labour. And in the United States, at least, the tenure and promotion process is staked almost exclusively on individual achievement. Our brains grow accustomed to this. There’s always a hierarchical structure that privileges the singularity of the individual mind or reputation.

I worked for over a decade on this piece–that is, the chapter about the Free Library’s copy of the First Folio that appeared a couple of years ago in the Early Modern English Marginalia collection. And that was indeed deeply solitary work. It involved me sitting in the library, basically collating the Folio against quarto texts. It was really boring and very laborious, though obviously it paid off in the end.

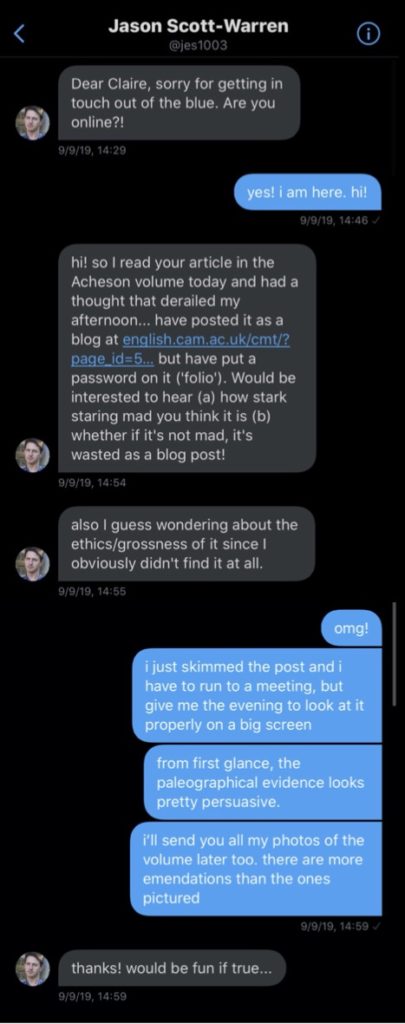

Then I sent this piece off out into the world. And I thought: well, maybe someone will read it. And then you have someone like Jason, who is one of the most generous scholars and humans I have ever met. He not only read the chapter but got curious about what he saw in the many grainy images that accompanied my analysis. He wrote up a whole blog post with his first pass at an argument identifying Milton as the reader and password protected it. Then he sent me a DM tweet, saying: I have this crazy idea; will you look at this? So the first thing there is, he’s asking me. He’s asking: will you look at this thing in this book that you are the expert on? So the first move of collaboration is to open the door and invite someone’s input.

‘Would be fun if true’: Jason and Claire’s initial exchange

I should also note that the editor of the Marginalia volume, Katherine Acheson, pushed hard with Routledge for me to be able to include an unusual number of images in my chapter. This is a form of collaboration, too. Even though there was no Milton connection at that stage, Kathy recognized the value of visual evidence to my argument about the reading practices evinced by the readers’ marks. Although I don’t love to deal in counter-factuals, it is probably the case that Jason would not have made the connection he did were it not for Kathy’s advocacy.

Once Jason publicised the blog post, things moved very quickly. And I remember him saying to me something like: I won’t do anything on this project without you; ethically, I can’t do this unless we do it together.

There’s also a practical aspect to our collaboration. I’m in the States, I’m near the book, and he’s not travelling because of his commitment to fighting climate change. But that certainly wasn’t the primary reason why he approached the project in the spirit of collaboration. At every step this project has been deeply collaborative.

INTERVIEWER

What have the challenges been in that process?

CLAIRE BOURNE

Jason and I have very different working styles. And we’re also each working on different projects alongside this. So, one challenge we’ve faced is how to find time to do our individual work on this project and then to correspond about it.

The email chains we have are really long! And full of energy and verve. I’ll do some work on it, and then he’ll do some work on it, and then there will be these overlap days where we’re both at our computer. When we were trying to track the genealogy of the person we think sold the book in 1899, we had three days where he was logged into ancestry.com, I was trying to figure things out from different angles on this side, and we were going back and forth, back and forth. It was so energising!

And there was no ego involved. If either Jason or I had different personalities, this might not work so well. I’m proud of the work I’ve done so far in my career and I don’t feel like I need to prove myself on this project. And I sense Jason is at a similar place in his career, although I obviously can’t speak for him. What that means is that the ‘discovery’ related to this book is a very nice thing, on top of all the other good things we’ve worked to achieve so far.

INTERVIEWER

Together, you and Jason seem to have figured out an amazing, networked model for what it means to discover something at this moment of early modern scholarship.

CLAIRE BOURNE

I hope so. And that sense of networked discovery extends beyond us. When the initial press coverage came out, it foregrounded the idea that this book had just been ‘discovered’. But of course this book was known before, and had been known since 1899. It has been included in all the censuses of the First Folio, and used extensively by the librarians at the Free Library up in the Rare Book Department in teaching and public programming. So when we talk about ‘discovery’, it’s not that the book itself was discovered, it’s that Jason saw it with different eyes. The contexts that Jason brought to this book were very different from the contexts that I had brought to it. That’s what’s exciting about this story and also why collaboration should happen more than it does.

One of the other points I want to make, though, is that collaboration does happen more than we think; it’s just not formalised. We see this most clearly in book acknowledgements, for instance. I could never have written my book without the help of the librarians at all the rare book libraries I used. I also could not have written my book without colleagues offering to read my drafts and commenting very substantively. So we should count all that as collaboration, too. Maybe one day we’ll figure out a way to change the structures, where we can co-write things without barriers, and without having to be senior and tenured. Collaboration shouldn’t be a reward, but in many respects, that is how it is at the moment.

INTERVIEWER

Kate Ozment’s essay, ‘Rationale For Feminist Bibliography’, explores our attitudes towards what has historically been recognised as valid academic labour. Part of her point was that there’s this thick layer of bibliographic labour–cataloguing, curating, collecting, but also things like work-sharing–that we tend to elide in book history. As your Milton discovery shows, you need so many different points of knowledge to connect for that final piece to click into place and for the whole thing to light up.

CLAIRE BOURNE

Yes. I’m reading Kate’s piece with a reading group next month. And I’m actually writing a piece for Adam Smyth’s Handbook of the History of the Book in Early Modern England [forthcoming from OUP] called ‘The Shadow History of a Discipline’. It is about the kinds of labour–mostly gendered female labour–that enabled male bibliographers to make the claims they made. So that will hopefully address work like cataloguing, but also the building of censuses and concordances. These are projects that are definitely scholarly and which make arguments, but they tend not to be the materials that are cited. But as Kate points out, those hierarchies are still very much in place and must be dismantled actively.

~

‘The best academic books are proof of concept of a method, and not a comprehensive account of a thing’

(4.) Early Career Academic Life

INTERVIEWER

Could you describe your route through graduate training and into getting your first job?

CLAIRE BOURNE

After I finished college I started a career in journalism and took a job as a reporter at an independently owned daily newspaper in New England. That didn’t last very long—the pace of the work and the kinds of stories I was being asked to cover made the job unsustainable. After freelancing a bit, I went to Oxford for the early modern M.St programme. I didn’t really know if academia was for me at that point. While I was at Oxford I worked with Tiffany Stern on my thesis, and I did okay—just okay. It took me a while to get used to the British system and figure out what was required from me in terms of research methods. In US undergrad classes, you don’t really do a lot of primary research; that’s very different in the UK. All of a sudden I didn’t quite know how to navigate the libraries, even at the level of basic things, like how to use a non-circulating collection. One year is not really that long to learn how to do these things.

I didn’t apply to a PhD programme straight from the M.St. Instead I came back to the States and taught at a high school just outside of Richmond, Virginia, for a year. As part of the fellowship I was on, I had an incredible mentor. She taught half a course load and I taught half a course load, but we sat in on all of each other’s classes, so I got to observe someone who had been teaching literature for twenty years do her thing and she got to observe me and we spoke about what worked and what didn’t work. In the end, it wasn’t so much the research aspect of academia that got me back in, it was the prospect of teaching. I’m grateful for that year because it’s when I learned how to teach. That’s not something that we get very much of in our doctoral training, at least I didn’t.

After that, I applied to PhD programmes. Penn was the only one I got into. I went to the prospective students weekend in Philadelphia that spring where the people I met were choosing between four different Ivy League offers, and there I was thinking: well, I’m coming here, because this is where I got in!

But Penn was the perfect programme for me. At the time it was going through a transitional moment with respect to its early modern cohort. Peter Stallybrass and Margreta de Grazia were almost retired, and Zack Lesser was fairly new. So there was a nice balance of old guard gravitas and this new exciting work that Zack was doing. It worked out very well for me. The timing meant that I was able to weather that 2008 dip in the job market, and was just very lucky to get a job right out of grad school in 2013.

INTERVIEWER

Can you talk a little about how you got that first job?

CLAIRE BOURNE

I was invited for five MLA interviews in my first year (back when MLA interviews were a thing) and pretty much bombed them all, except for one. I wasn’t practised at speaking about my work and I had major imposter syndrome. But the interview I had with Virginia Commonwealth University actually went well–you can feel in your gut that you’ve been involved in a great conversation. But then I never got a campus visit.

Through the grapevine I heard that the dean had decided not to bring anyone who didn’t have a degree in hand to campus. But I was also told through the grapevine to hold on tight, and that I was an alternate. And because all the other people they brought to campus presumably got other jobs, they ended up bringing me to campus as their reserve choice and then hiring me.

So again, I’ve been very lucky. I got into one master’s programme, one PhD programme, and got one job offer. And all of that was contingent on circumstances outside my control that worked in my favour. I couldn’t have asked for a better job. Life circumstances led me to go on the job market again (which is how I ended up at Penn State), but I would still be happy at VCU if this move hadn’t happened.

I don’t need to say that the job market was, and still is, deeply capricious, at best, and almost non-existent now with the additional layer of uncertainty caused by the pandemic. The scarcity of jobs takes a huge toll on your sense of self-worth and of the value of your work. After working for six years on something, it’s hard to send that reflection of yourself out into the world and not get anything back, which is basically what the circumstances are at the moment. It can be devastating. Applying for jobs is itself a full time job, and not just the labour of applications but the emotional labour of putting yourself out there. Everything we do in this profession—teaching, writing, constantly applying for financial support—involves emotional labour.

INTERVIEWER

How do you deal with that?

CLAIRE BOURNE

Therapy.

INTERVIEWER

Good call.

CLAIRE BOURNE

I talk to a therapist once a week, and she understands the way academia works and how it is changing. That has helped me to understand that my greatest strengths are always also my greatest weaknesses. So, for example, I’m meticulous in my scholarship: I’m very detailed-oriented. And that’s good. But in some ways that level of attention can be so overbearing that it can break me. So the challenge becomes figuring out where to set boundaries and how to keep an eye on the balance. It is important for me to find where to set boundaries in my professional life so that I can also be available to myself, my family, and my friends, of course, but also to students. The challenges they’re facing today are not necessarily the same as the ones I faced, either as an undergrad or graduate student, so I need to be alert to that as I help them navigate through their degrees and into their professional lives.

INTERVIEWER

Could you talk about the role of physical exercise in your work life?

CLAIRE BOURNE

Exercise—perhaps ‘fitness’ is a better word?—is a deeply engrained part of my work life. When I was finishing my dissertation a friend invited me to some indoor cycling classes in Philadelphia. I ended up going a few times a week as I finished up my dissertation, and became hooked. I never thought I’d be a group fitness person; I thought it would make me feel vulnerable. But I loved it!

When I came here to Penn State, one of my colleagues in the English department, who co-owned a fitness studio, invited me to join. So I started going to classes there and at some point they needed a new instructor. My colleague knew that I was interested in teaching, and she asked me if I would go to training. At that point I was in the middle of working on my book and I needed something else, some other kind of engagement for my brain. So I trained to teach an ‘immersive’ cycling class, where you ride facing a floor-to-ceiling screen. It’s like riding through a video game—so much fun! I also trained to teach a more traditional indoor cycling class. And last year, I got certified as an instructor for a high-rep, low-weight strength training class. It changed my health and my life!

I also walk a lot, usually around eight kilometres a day around my neighbourhood. And the rhythm of that establishes in my body helps me with my writing, too. I think that physical wellness goes hand in hand with mental wellness and with–I don’t like using the word ‘productivity’–but physical wellness certainly helps with making the things that we make in our profession, whether that’s lessons for class, or pieces of writing, or books, or editions.

I have built exercise into my daily routine: indoor cycling, HIIT, strength training, flexibility and mobility training, &c. Variety is key. Also, you can’t work out seven days a week; you’ll injure yourself. I always take one full rest day a week. And I take that to heart with my academic work as well. I am trying hard to make time to rest and recover so that my brain can be on when it needs to be on.

~

The index for Typographies of Performance: ‘These pieces of your book are broken apart and sidle up against each other in strange ways’

(5.) Editing

INTERVIEWER

How are you finding working on an Arden edition?

CLAIRE BOURNE

It’s challenging, but great fun. I’m early in the process. I’m editing Henry the Sixth, Part 1, a Folio only play. It’s not all that textually complicated, at least on the surface. But at the same time, it’s a weird text, especially in the inconsistent naming of characters across the Folio text. The Arden 3 edition was the only Arden edition where the general editors added a note disagreeing with the editor of the volume [Edward Burns] about a choice that concerned how he chose to name the characters, especially Joan of Arc. So editing this title feels like stepping into a bit of a minefield.

This play is also at the centre of a lot of new work on attribution studies. It’s very Marlovian in its feel. I can’t yet assess the validity of the recent attributions to Marlowe and Nashe–we don’t have the resources to do that. But one of the things I’ve been doing in preparing to edit the play is teaching it a lot. It’s always been on the edge of the Shakespeare canon because of the potential that it was cowritten. People have suggested it’s not really that good of a play, and it has been disparaged a lot. But, my goodness, does it teach well! And that’s one of the things I want my edition to show.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have a sense of any ideas your edition is going to embody?

CLAIRE BOURNE

One of the pitfalls of editing a history play is the assumption that you’re going to deal heavily with sources. I think there’s this expectation for you to set out whether the play gets its sources ‘right’ or ‘wrong’. And obviously I will deal with the play’s sources but I’m less interested in them in that factual way. Instead I’m interested in how playwrights took source material and reworked it as drama. I find it interesting that the timelines in the play don’t match up with the timelines of history, but my focus there is on the question of what that says about the dramatic effects the play produces. I’m then also interested in how the Folio text mediates these effects, if at all.

Also, questions of militant white nationalism are on full display in this play, as it toys with audience sympathies for characters who do horrible things. So these are issues that I want to tease out and make available to new readers as I prepare the text. But I still have a lot of learning to do in order to frame this aspect of the text responsibly. The series of virtual #ShakeRace and #RaceB4Race events sponsored by the Folger, the Arizona Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, and other institutions over the summer and fall, as well as ongoing Twitter discussions about the intersections of race and Shakespeare, have been helping me prepare for some of the work I still need to do.

In the end, I want to make this edition one that inspires people to want to teach and stage this play; it’s an interesting and urgent text, fully resonant with our current political moment.

~