paper kingdoms 2: adam smyth

Professor Adam Smyth, probably, in his office at Balliol College, Oxford

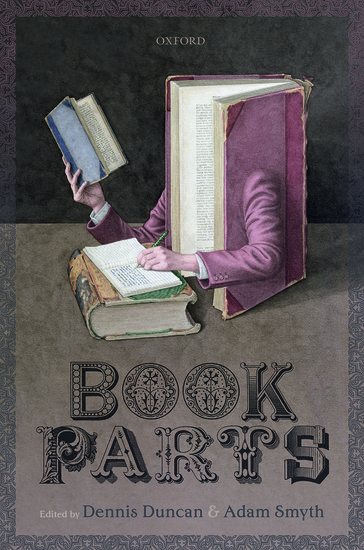

Adam Smyth began his career at the University of Reading before moving to Birkbeck College, London. He came to Oxford in 2013, to Balliol College, where he is now Professor of English Literature and the History of the Book. His scholarship is marked by a brilliantly focused curiosity and the ability to make material that might seem unyielding – printed waste, typographical errors, fragments of flowers found in old books – come alive with critical interest. I once gave a presentation on ideas of ‘wondering’ / ‘wandering’ in the work of Sir Thomas Browne during a job interview in which a panelist, unprompted, mused on links between Browne and Adam’s writing before leaning in with their next question. Adam is also a particularly productive member of the early modern community. He has written three monographs – most recently Material Texts in Early Modern England (Cambridge, 2018) – and has edited, or co-edited, four collections – most recently Book Parts with Dennis Duncan: a collection of essays on the history of parts of a book (Oxford, 2019). You can read more about his current research interests on his Balliol and English Faculty websites.

This interview took place in Adam’s office in Balliol College, which is a happy clutter of books, cards, papers of various kinds, perched at the top of a staircase. He is an interested and animated talker who enjoys the shared back-and-forth of conversation but also occasionally sits back to think something through with particular precision. We spoke on a Friday evening amid a busy term about the challenges of editing an Arden; the strange, slow process by which a book emerges; and why he is only seventy-three percent an academic. Inspired by the note-taking practices of its subject, I have crumbled this interview into three distinct topics: Reading, Writing, and Thinking.

1. READING

INTERVIEWER

What have you read recently that you’ve found inspiring?

ADAM SMYTH

I enjoyed Jason Scott-Warren’s book, Shakespeare’s First Reader [Penn, 2019] which is about Richard Stonley, who gave us the first record of a purchase of a Shakespearean text when he bought a copy of Venus and Adonis. But Jason’s book tries to park that riveting nugget and do everything else it can with the records of Stonley. It becomes an enactment of a Rita Felski-ish idea of surface reading.

I’ve recently been re-reading Juliet Fleming’s Cultural Graphology [Chicago, 2016], which I’m always challenged by and love. I also read Lytton Strachey. His piece, ‘Shakespeare’s Final Period’ from the Independent Review in 1904, is spectacularly of a different moment to our moment. But I was struck by its brilliantly cavalier recklessness of judgement. It’s saturated with a familiarity with Shakespeare but also polemical and suggestive and quite plausible. If we’re interested in thinking about different registers of writing, then nobody writes like this anymore.

INTERVIEWER

How do you organise your research notes?

ADAM SMYTH

Currently, I have a red notebook which I treat as an out-an-out ‘ideas’ book. There’s stuff in here about what I’m music I’m listening to [flipping through pages], things about the Beatles, stuff about the Book of Exodus, Marshall McLuhan, the question of what a source is…

INTERVIEWER

And you carry this book around?

ADAM SMYTH

Yes. In a bag or pocket. With a Pilot G Tec C4 pen. It’s a kind of form of diary writing – stuff that comes at me. I don’t date the entries, but it’s chronological or seriatim. Today I had to go through M.St feedback and occasionally a phrase struck me that I wrote down: ‘pagination would have been helpful’. Someone was referring to ‘discard studies’ which I hadn’t heard about.

Then I have another notebook, which is largely a diary, but at the back has alphabetised pages which I think used to be an address book. I use it like a commonplace book. So ‘C’ is ‘culture’, things I want to see: British Library Hebrew Manuscripts exhibition; Wittenham Clumps; Gauguin… These are things I want to do. I find it quite stressful when I read things that are compelling because I think I’ll forget them. So I put them down here, and every now and then I’ll go back to it. Here is ‘mudlarking’, but I’ve crossed that out because I did it.

On my computer I have EverNote and Scrivener. For a while – I’ve stopped this now because of EverNote – I had an actual commonplace book, a larger, alphabetised notebook. I started it because I had a crisis of notetaking. I would go to talks, take notes, and those notes would become immobile and unhelpful. So I started to try and crumble the talk into different headings. If it was an interesting talk that said something about editing and something about London then I would make entries under those headings. That’s good to go back to because it’s already partly digested.

INTERVIEWER

Quite a lot of handwritten methods.

ADAM SMYTH

Yes. I like – as everyone does – the Moleskine and my G Tec C4. But I don’t quite believe in the long-termness of the computer record. I need the physical record.

INTERVIEWER

You’ve written, in relation to Ben Jonson’s ‘An Execration upon Vulcan’ [Material Texts, pp. 55-74], about ideas of haste and slowness in literary production. Is there anything relevant there about your physical notetaking process being slower and more laborious than working digitally?

ADAM SMYTH

I used to copy pages and pages out onto a computer. In the late nineties, while I was doing my PhD, I would spend the bulk of my time simply copying out stuff from early modern print. I had a card index too, which helped me to produce a digital database of verse miscellanies. Before it was online it was a series of index cards, and I used to transcribe these miscellanies, writing out the first and the last line on these cards, and they would gradually accumulate. But now, it would be a rare moment where I was simply, with monk-like attention, copy one text into another. But that was probably sixty percent of my time early on.

I was at a restaurant with my in-laws a while ago, and at a certain point my brother-in-law got his phone out and pressed record. I realised he was taking a note of what we were talking about to remind him to do something. There was something about the slippery ease of that that I found kind of uneasy and unhelpful, in contrast to the analogue, annoying, slow notebook. There’s a little hump of resistance you have to get over.

INTERVIEWER

Do you ever feel anxious about having notes in diffuse repositories?

ADAM SMYTH

I have dozens of physical notebooks, and sometimes I wonder how active they really are.

I suppose it’s whether we think about making notes as acts of remembering or acts of forgetting. In some ways, you write it in the notebook and it takes the pressure off. You might think, I’ll come back to it, but I don’t need to think about it just now. I think that’s how I often feel about notetaking. It’s a release, or a parking of useful information. But that can also easily become a version of forgetting. If I was doing it properly I’d need to review the whole thing. But then you become Casaubon in Middlemarch, shuffling all your material around.

~

2. WRITING

INTERVIEWER

Have you ever struggled to write?

ADAM SMYTH

I really enjoy writing and find that writing is also where I do my best thinking. I like being in the state of writing. I always remember Žižek talking about writing. He was being interviewed about how he writes and his productivity. He said ‘I hate writing. I can’t write and find it impossible.’ And the interviewer said, ‘But you write seven books a year. How can this possibly be?’ Žižek replied by saying that he had eliminated writing. ‘I read and I take notes,’ he said, ‘and then I edit the notes into a book.’ So the terrible moment of writing with a capital W disappears. I’m always taking notes, I’m always drafting things. So I never have that vertiginous, first word on a blank screen moment.

INTERVIEWER

You’re always drafting things?

ADAM SMYTH

Yes. There’s always bits of text to shunt around and organise. There’s never nothing there.

INTERVIEWER

Could you describe the anatomy of one of your chapters? How did it come into being? What problems did you encounter?

ADAM SMYTH

Yes. Let’s talk about the waste chapter [‘Printed Waste: ‘Tatters Allegoricall’’ in Material Texts, pp. 137-74].

This chapter initially began with my file – it’s just a Word file – of interesting things or leads, in which I would note down odd bits or bibliographical or literary strays that I couldn’t make sense of in the moment. Instances of printed waste first cropped up in there. Occasionally they had been catalogued in more rigorous places like the Folger or the Bodleian, but not always and sometimes not at all. And it seemed that no-one really was talking about these things. I found that a lot of bibliographical cataloguing work had been done on manuscript waste, though not much interpretive work. So I began by thinking: here’s an odd bit of text and I don’t quite know what to do with it. It’s there often, I’ve got lots of examples of it; it’s sort of invisible to me and other readers, but it’s also loudly weird. Here’s a bit of Cicero in the Bodleian’s copy of Shakespeare’s First Folio, for example. The kernel was just that this was an odd feature of a printed book that needs exploring.

The first stage was just going around and accumulating lots and lots of examples. That meant using catalogues to some degree, but it mainly meant – and this was key to this whole book – writing to librarians, in college libraries, university libraries, in England, in North America. I probably wrote fifty or sixty emails to different librarians. I was interested both in whether they had any examples of this phenomenon, and also how they handled it. The institutional trickiness of waste was part of its appeal. I got lots of interesting answers back to both of those questions, enough to suggest there was something challenging about waste as a form.

So then it was a process of gathering stuff, going around many libraries and getting examples: meeting librarians, taking photos, describing the material, and pooling that into one single big Word file with loads of examples. Then I had to think about why this was interesting, what questions this material suggested. I suppose the hybridity of my book as both literary-critical and bibliographical became important, because I was instinctively interested in these examples for their literary life and interpretive potential. Partly because they spoke so vividly to contemporary artists’ books and this moment we’re in of people doing interesting things with the book as a form. And also because the amazing scholarship that’s out there – the work on manuscript pastedowns, for instance – was not at all interested in those sorts of questions.

Writing the chapter became a process of posing those questions to that material. How do we read it? How did early moderns read it? How does it challenge terminology? Is it a bit of waste, or a host? Is it excessive or is it key? Is it material text or is it literary text?

INTERVIEWER

What was the first part of the chapter that you wrote?

ADAM SMYTH

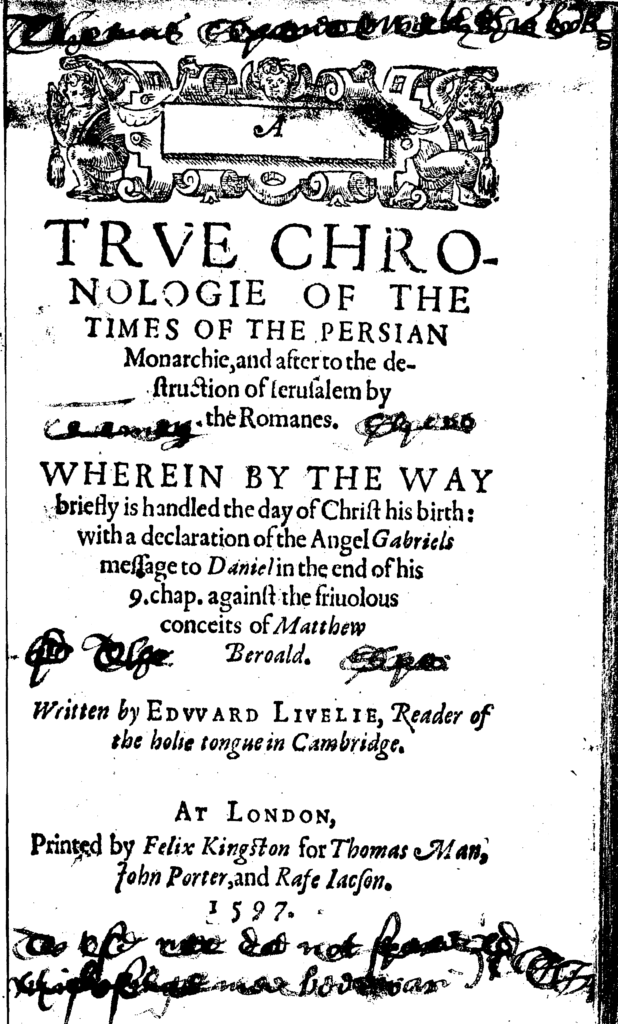

I definitely didn’t begin at the beginning of the chapter as it appears. I began, as I nearly always do, with a situated case study. I think it was the instance of this interesting book by Edward Lively, A True Chronologie of the Times of the Persian Monarchy (1597), a copy of which in the Bodleian has printed waste from Sidney’s Astrophel and Stella. And that seemed so provocative, that Sidney’s Astrophel and Stella, which for literary critics is one of those decade-defining texts in one of the most important decades in English literary history. And here it was, ripped up and used as padding for this little-read history of the Persian monarchy. It seemed so out of line with how we would think about this period.

So I think I began, as I usually do, by trying to describe this artefact with as much specificity as possible. And then out of that came all these questions about value and canonicity and interpretation and priority and terminology and institutional responses.

Lively’s True Chronologie (1597)

INTERVIEWER

Is that a typical model of your writing, that you’ll start with a case study?

ADAM SMYTH

Yes. Definitely. That’s partly a product of the difficulty of finding this kind of material. You tend to stumble on individual instances. And though I piled up quite a lot, it was still not a mountain of examples. Which made this a case study chapter, and this is a case study book. There are drawbacks to that, in that case studies are good at provocatively challenging broader narratives, but it’s harder to build bigger histories from those case studies. So one of the projects I’m concerned with right now is trying to build a big database of waste, where, in a collaborative way, we’ll get not just the dozens and dozens of examples I found, but rather thousands and thousands of instances of printed waste. Hopefully out of that some interesting economy will emerge to do with how books were fragmented and circulated and used. But this chapter is definitely a literary-critic’s case study approach.

INTERVIEWER

Were there any problems you encountered in writing the chapter?

ADAM SMYTH

The chapter uses these examples of printed waste to think about certain quite fundamental questions about how literary criticism and bibliography intersect, and about how particular texts seem to flicker between the literary and the material. When I realised I wanted to raise those questions, and keep them alive, then I knew I’d found the important thing that would make the chapter work. To the bibliographer, understandably, it’s too local and seizes on obviously literary examples, and thinks about questions which aren’t perhaps so pressing for them. And for the literary critic it avoids reading this interesting chronicle history and turns the book sideways to look at a torn fragment, which seems perverse and paradoxical. It’s somewhere between the two.

Hopefully the chapter is a kind of transcript or account of my thought process through time with this object. I never read a text, think about it, reach a conclusion, and then write an articulation of that conclusion. I always see the writing as an account of thinking through this object. It’s not quite real-time, but it’s definitely a talking through of this thing from different angles, walking round it, holding it up, seeing where that leads. And sometimes that leads to dead ends that don’t work out. But I’d like to convey that present tense.

It was important for me when I realised that academic writing could be a thinking through of things. That took the pressure off to a great extent. All the doubt and uncertainty of working through – which can be the thing with which one has an agonistic relationship – those things became the material. I think this partly comes from my feeling only about seventy-three percent an academic. I really like being an academic but I also slightly feel like a journalist, slightly like an academic entrepreneur of some kind, who organises things. And I like that slight ill-fit.

INTERVIEWER

Can you think of any dead ends for the waste chapter that didn’t work out?

ADAM SMYTH

I’d hoped to speak to the book historian crowd. I’m sure it’s the case that one of the things you can do with printed waste is to use it as a material link between certain stationers. There’s a fraternal pairing of Roger and Joseph Barnes in Oxford, and some of the waste seems to be moving between them – predictably, probably, but it confirms the intimacy of that bond. I think those maps will emerge in time, but they couldn’t in this chapter. So that remained more of a hope.

The other thing about this chapter is that I’m not really interested in Presentism. Which is quite a loud presence in our field at the moment. I’m interested in the strange alterity of these books located in the past, how they operated in those past periods. But this chapter is definitely slightly informed by my long engagement with Tom Phillips’s book The Humument. In the 1960s, Tom Phillips bought a Victorian book called The Human Document, published in the 1890s. He painted over most of it, leaving these little trickles of text behind, and created this hilarious counter-voice. It’s a fascinating conversation with this 1890s book in which something else emerges. That was definitely in my head as I was doing this chapter about printed waste, which is about finding incongruous juxtapositions or surprising animation in texts we thought we knew.

INTERVIEWER

You’re someone who cares deeply about your prose and I think writes in a more literary way. You often use imagery to animate the ideas you’re discussing, for example. Can you say anything about your prose style?

ADAM SMYTH

I’m quite often talking about stuff that seems quite tedious to quite a lot of people! And I do think that a lot of my critical work is at least in part an attempt to persuade people that this is worth looking at, this is interesting. One common refrain across my work is taking unpromising material and showing why it’s worth thinking about. When I do reviews for the London Review of Books, for example, I think they almost deliberately give me stuff that seems arid to see if I can animate it. One consequence of that is that I try and write about it in a lively way. I find this work exciting and try to convey that.

INTERVIEWER

Where are you when you usually write?

ADAM SMYTH

I don’t have a single space. It’s a combination of the train, a bit in my office, a bit in the Weston Library, a bit in the London Library, a bit at the kitchen table, and a bit in cafes.

INTERVIEWER

Do different spaces influence your writing in different ways? On a train you’re not tethered to a particular set of circumstances or institutional environment, and that might be freeing.

ADAM SMYTH

Instinctively I would say yes, but when I write I pretty quickly lose a sense of my surroundings. To be honest, if I’ve got a chance to write it’s normally such a pleasure and such a treat. The writing is always the reward, so it’s something I approach with a delight akin to watching a film or going for a nice meal.

A friend of mine at Columbia told me I was too quick to write, too fluent. I don’t find it an agonistic battle to write. I enjoy being in the process of writing, and even more now, given that it’s hard to get to it because of life and work and teaching. If I can find an hour or two hours, I’m happy.

The other thing is, I don’t think you need to write very much in a day to be writing. We have this terrible nine to five paradigm that’s imported from other worlds of work which is totally inappropriate. Maybe some people do that, but if I can do anything like four hours in a day, that would be a fantastic triumph and I would be really tired at the end of it. It’s healthy not to think about writing in terms of anything like a day of work. When I have a writing day, anything more than two hours of proper writing is really great.

INTERVIEWER

Do you always sit down knowing what you’ll write? How much do you plan?

ADAM SMYTH

I never have plans for my writing. If I did start one it would quickly stop, and the eventual thing would not follow the plan at all. Instead, I read and read and read, and take notes, and then just plunge in to the most immediately interesting bit. So for the printed waste, I knew that the Sydney example of the Astrophil and Stella waste was just arresting. I didn’t know what I would say about it, but why start with a tedious framing introduction? Go to the exciting thing first. And then your chapter leads out.

Let’s take editing Pericles as an example. This is a different kind of scholarly work entirely, one that seems less prone to my ‘plunging in’ method. But even here, when I had to prepare a sample scene, I knew I had to do Act 3 Scene 1, the amazing storm scene. This is the moment people think that Shakespeare takes over the writing from Wilkins. Whether or not that’s true, there is, I think, a leap in quality in terms of the writing. So I thought: let’s start with this. It’s the most fun, it’s the most difficult, the most interesting bit.

INTERVIEWER

Do you write on a computer or longhand?

ADAM SMYTH

Definitely computer. Notes by hand but computer for writing. And I use Word.

INTERVIEWER

Do you re-write much?

ADAM SMYTH

I usually write to a quite finished level, then print out, then correct by hand, using traditional proofreading symbols and marks. Then I enter those back in and look over it one more time.

INTERVIEWER

That suggests that your process of revision is separate from your writing process?

ADAM SMYTH

Definitely. I do think about those as different actions. Last week I went to Antwerp to the Plantin-Moretus Museum and was really struck by their separation of the book into different spatial bits. There’s a proofreader’s room; a typesetter’s room, and so on. And when I print out my work onto a different medium I’ll go into a different room to correct it. I enjoy correcting by hand.

INTERVIEWER

Why is it important that you correct by hand?

ADAM SMYTH

I think it’s something about holding the whole thing at once. Even though it’s on different pages you can hold the overall shape in ways that escape you on a computer. I like seeing that I’ve produced something! That’s reassuring.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have a favourite font?

ADAM SMYTH

I do think about font a lot, but I’m quite changeable. I have some fierce but local commitments. I’m using Calibri at the moment, but had a long phase of Garamond, and obviously Times New Roman is the square one we all depart from. Wingdings less regularly. Courier if I want to produce a hipster hamburger menu. I think I use them as a sort of refresh boost, like a drinking a shot or something. It slightly estranges or freshens the whole thing.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have any particular habits or rituals or props that help your writing?

ADAM SMYTH

I basically enjoy writing, so don’t spend too much time lingering at the side of the pool before jumping in. Lots of cups of tea and coffee?

The one thing all of us have to deal with is how to engage with the internet or not when writing. There’s a kind of tyranny in its distraction. It offers you a Platonic everything, all the time, so how could that not be more interesting than your quite difficult writing? I’ve tried various things to help with that. I’m not quite with Jonathan Franzen but I do think for all kinds of reasons the internet is a terrible thing for writing. The thing I have done is leave social media. I had a terrifying moment about five years ago when I went to the library for the first time in quite a while to write, and was really struck by how much my concentration had withered away. I was finding it hard to do more than half an hour at a time. That was a real jolt. So I’ve tried to uncouple myself from Facebook and Twitter. I’ve junked my smartphone and have a ludicrous orange Nokia, but that’s definitely helped.

INTERVIEWER

Your writing explores the possibilities of various forms. You write creative work and reviews, but even in your academic work you often use other formal techniques. Material Texts finishes with a list of current disciplinary concerns; the second half of your cutting chapter is a list of seven or eight ways to think about cutting. Do you think much about form?

ADAM SMYTH

I think it’s weird to be interested in literary texts and not to wonder about the relationship between the form of your own writing and the form of the texts you’re studying. I do think about it and I do like lists and headings. I like that lists are suggestive rather than definitive. I’ve got no interest or ambition to have the last word or settle things. But I am interested in launching questions or projects for other people to think about. The list is good for that.

We’re at a particular moment of creative critical overlaps. I think you can do that loudly by collaborating with a theatre or an artist, but you can also do that at the level of prose by importing some of the life of your subject of study into your own writing. Or at least think through your subject through the form in which you’re writing.

INTERVIEWER

I feel as though criticism at the moment is stepping back from closed narrative and resisting what might at one stage have been seen as the responsibility of a scholar to interpret and then to conclusively convey something definitively.

ADAM SMYTH

Jeff Dolven’s book Senses of Style is a good example of that. This is his book on the implausible coupling of Frank O’Hara and Thomas Wyatt in order to think about the idea of ‘style’ – such a seemingly common-sense word that he unpacks in magnificent ways. His book is written like a manifesto: numbered paragraphs, short aphoristic, suggestive points about style. Partly that’s in conversation with his topic, and I think partly its about our uncertain moment. But there are cruder institutional reasons too. Something like ten years ago, institutional pressure for academics to collaborate with non-academic partners led to a first wave of rather clumsy, pragmatic collaborations. That’s created a culture in which writing more expansively or creatively is a real possibility for academics.

~

3. THINKING

INTERVIEWER

Your monograph Material Texts was recently published. Do you have the next project in mind? How do you navigate that in-between stage?

ADAM SMYTH

It’s complicated. Material Texts was actually finished quite a long time ago and feels in some ways quite distant. It was published in very late 2018 – in some places I think it was 2019 – but I had finished writing it in probably 2017. So it feels quite distant. But it’s also recent, in that the great flood of reviews I’m expecting has yet to burst the banks. And in terms of people talking about my work, or asking me to do talks or write things related to that book, it’s very present. So I am ‘post’ that book, but quite how far post I am varies depend on how you think about it.

It’s a very nice feeling when you finish something, even though the finishing is difficult to pin down to a moment. Usually I have this euphoric sense of dusting my hands off and entering new vistas, entirely new work. And then I start working and realise it’s exactly the same as what I was doing before. So since Material Texts I’ve done the Book Parts book, which was more entrepreneurial and involved getting the contributors to get their stuff in on time. And I’ve done a more creative piece called 13 March 1911, which is a small book about a single day. I didn’t know what that would be till it was finished, but it was ticking away, occupying a slice of what I was thinking about. It became a kind of textual collage about all the things that newspapers told us about on that day. But what’s really on my desk at the moment is editing Pericles.

So I suppose I’ve enjoyed, and deliberately tried, to work in different registers, to pursue different kinds of writing. I like the granular, super-slow, viscous editing of Pericles, which you just cannot rush. It’s a magnificent resistance to haste.

INTERVIEWER

Have you always moved between different projects?

ADAM SMYTH

I’m doing it now more than I ever have done. I think in my academic writing, early on, I tried to be a bit looser and more sprightly and mobile than might have been predictable. But it was still only academic writing. But then I started doing reviewing, which I think became a big thing for me. That became really important and I would recommend it.

INTERVIEWER

Why was reviewing important for you?

ADAM SMYTH

I did lots of Times Literary Supplement pieces early on. Which meant that I read lots of books all the way through. Which is weirdly rare for us to do, to read a whole book from start to finish, makes notes, think about it, gather your thoughts, have a view. So that gave me a really good sense of what was happening. For about six years I probably did about six or seven pieces a year.

INTERVIEWER

That sounds a high turnover.

ADAM SMYTH

Yes! I was working hard, but I enjoyed doing that. Lots of them were quite short, which made them a good exercise in brevity and clarity and getting to the core of things.

I also thought a lot about my reviewing register. For a long time I did dutiful summary and polite affirmation. And then at a certain point I thought, it’s much better to go really hard on the things I like, and equally hard on the things I don’t like. What do I want if a read a TLS review? I want a clear sense of what the book is about and whether I want to read it, but I also want a kind of feisty engagement; I want something picked out and praised, and some proper criticism of it. So I had that reviewing voice running all the time for the TLS, which after all is a generalist paper, somewhere between Modern Philology and The Sun.

INTERVIEWER

How do you start a research process?

ADAM SMYTH

It’s difficult to pinpoint one moment where a project comes into focus. For my second book, about autobiography, I have a sense of that beginning. Autobiography in Early Modern England began with a long-term fascination with the diary as a form. I love reading diaries. Virginia Woolf’s diary is one of my favourite books; Simon Gray and The Smoking Diaries; Pepys, obviously. So I thought, I want to do something with that.

But that was really as developed as it was. I thought, I don’t think there’s a really good book about early modern diaries. I had this naïve idea that I would go out into the wilderness of local history centres and archives and find all these early modern diaries, these Pepyses out there waiting. And the Access to Archives site did indeed suggest there were all these interesting manuscript diaries out there. So I toured archives. I went to the first place and ordered my stuff and it came, with all the romance of the box and the lid and the unread stuff. But they weren’t diaries, they were account books and financial papers, scraps. So I noted them and thought, that’s not what I’m after. But the same thing happened at the next one, where I maybe got a commonplace book and a parish register, and all these odd forms kept arriving. At a certain point I thought, this book isn’t happening.

But then I thought actually this is really interesting. These things clearly have something to do with diaries. They’re all catalogued as diaries. They’re kind of first-person records, transcripts of experience of life. The project shifted, from being this excited but naïve sense that I would find dozens of diaries to the realisation that there’s this whole sprawl of diary-related texts, which get flattened through our modern terminology.

So that project began with naïve enthusiasm that was tested in the archive, crumbled – and that was a low moment – but then I realised that all these little granules of lives were really interesting.

INTERVIEWER

Jason Scott-Warren, in Shakespeare’s First Reader, picks out your book’s interest in finding lives in a dispersal of documents and forms as being one of its most important contributions to life writing. That seems a positive story about a stage you might feel would take the bottom out of your project becoming its strength.

ADAM SMYTH

That model exemplifies lots of things that I think are important. The gap between our expectations and categories and their early modern equivalents, for example. The ill-fit between what we expect to find and what we do find. And trying to spend enough time with those textual forms to understand their own logic.

I remember looking at Lady Anne Clifford’s life writings in Kendal in Cumbria. They’re these massive folio volumes, hugely complicated as forms. They start from different ends, they’re cross-referenced, there are mini-accounts of the composition of the text within the text. I remember spending day after day trying to walk around this weird mansion of a book until it at some point I figured out how it was working. That was really fun. Just spending enough time to get inside the logic of this weird book.

INTERVIEWER

It sounds like there were distinct challenges during your Autobiography book that required the confidence to hold the course, and to know that you could adapt the project as its contours came under strain.

Do you think it was important to the way that you navigated those challenges that this was your second book? How had you evolved as a scholar since your first book [Profit & Delight: Printed Miscellanies in England, 1640-1682]?

ADAM SMYTH

I think I had evolved, in some ways. The thunderbolt moment for me as an MA student was looking for the first time at an actual early modern book, rather than an edition or something digitally mediated.

It was called Wits Interpreter, from 1655, and was a collision of conduct book and verse miscellany. It’s a fascinating text. But I remember the thrill of its oddness and strangeness as a form. There were poems I recognised as Shakespeare’s or Jonson’s or Donne’s, but which didn’t have those names attached and which had these weird variants and were cobbled together amid other strange texts.

My first book explored ideas about poems without authors, readers changing poems, and the realities of this variant-rich unstable culture. Which has been written about lots now, but then not quite so much. That book was restricted to a tidier form – I was looking at the printed miscellany – but I still recognise some of the themes of inconstancy, and fundamentally of finding something that was strange or unsettling and then trying to live with and explore that weirdness on its own terms.

Wits Interpreter (1655)

INTERVIEWER

Your writing often asks questions that seem simple but are actually directly challenging even to your own work, such as, ‘what can we make of this?’.

ADAM SMYTH

I think it’s important to ask very clear, axiomatic questions. Even starkly clear. And I often say this even to undergraduates: clearly pose these fundamental questions, and that’s a good way to organise things. I was influenced early on by certain people who did that very well, like Emma Smith, who clearly and boldly asks ground-level questions from which you can build up. Or my former colleague Sue Wiseman, who is also very good at that. Or my friend Juliet Fleming, who often produces these very difficult, dense texts in some ways, but they’re usually driven by thrillingly direct questions.

INTERVIEWER

There’s a moment in chapter three of your Material Texts book in which you’ve compiled a detailed table of cancellantia in the text of Elizabeth Hastings’ funeral sermon. The table is a model of bibliographical complexity and must have taken some time, but you immediately ask whether the table is ‘profitless bibliographical industry?’

ADAM SMYTH

Yes. Is this just a waste of time?

INTERVIEWER

The mood of that question will usually be hostile, asked across a disciplinary divide. Either you’re a bibliographer who holds the value of that kind of labour to be axiomatic, or as a literary person you just won’t be interested in that labour and so will avoid it.

ADAM SMYTH

The virtue of that is that you can toggle between these two positions and see things from both sides. You can see the interpretive life in the material text, but you can also see the virtue of that slow, careful method as well. The downside is that you have a slightly confused relationship to your audience sometimes.

For example I gave a talk about printed waste, which is another thing I’m interested in at the moment, meaning bits of old printed books that get torn up and used in new printed books in material form. I spoke to a bibliographical audience, and was trying to push the literary life of these fragments. So, if there’s a little piece of a Sidney sonnet trapped sideways in a chronicle, then what are the interpretive consequences of that? But they weren’t really interested in that. And from the other side, there’s some scepticism about why material form matters to these literary texts in a fundamental way. You’re not looking at the literary text in the eye, you’re sliding to the footnote or the binding.

But I quite like that slightly agitated sense of a confused audience, and being between. I think that’s helpful. Though that kind of literary-bibliographical work is itself becoming a field, with people like Zachary Lesser and Jason Scott-Warren and all kinds of people. If we go to a conference, there’s an audience for exactly our kind of work. And that little pushback, which from the bibliographers is always asking for more rigour and detail, and for the literary people is a scepticism about why this matters, I think it’s good to keep that resistance.

INTERVIEWER

How did Material Texts begin?

ADAM SMYTH

That was much harder to put together as a book than my previous work. There’s a kind of coherence in that each chapter is about a feature of the material book that we might not expect to encounter as twenty-first century readers – cutting, burning, error, and waste – but which was fundamental to the early modern book. But it had a long process of organisation.

At first it was about Little Gidding, the religious community outside Cambridge. This community was set up by Nicholas Ferrar, and one of the things they did was to buy printed bibles and to cut them up then piece them together in new harmonised forms. I wrote a piece about them and did a couple of conference papers.

But at the same time, I was speaking to a literary agent about writing a trade book. She liked the idea of Little Gidding. So I drafted a proposal for a trade book that was about Little Gidding in ways that I now find excruciating. It was going to be one of those academic books in which there’s a strong first-person presence: ‘I walked down the very streets where T. S. Eliot stood’ – that kind of book. This was about 2008. I had moved from the University of Reading to Birkbeck in London, and I thought about this proposal for quite a while, but it didn’t work.

But then, bizarrely, I was asked to be in a TV programme called The Century That Wrote Itself, about the seventeenth century and life writing. Basically everyone I knew was in it. I did a section on seventeenth century diarists in Soho which was really fun. And I spoke briefly with the TV people about making a Little Gidding TV programme, though that died and didn’t happen. So Material Texts was originally a failed trade book, then a failed TV programme, but I was always interested in it.

Those failures made me sit down for the first time in a strategic way and think: how can I turn this into a book? I’m interested in Little Gidding and cutting up, and had also become interested in mistakes and errors. I wasn’t aware of printed waste at that point, but I was interested in book destruction and burning. So I tried to put them together as chapters under a banner of the particular strangeness of the material text in the early modern period.

INTERVIEWER

How important is your academic community to your research?

ADAM SMYTH

Community is really important. On the one hand I do think, still, that the gold standard is the monograph. That’s the form that’s going to endure, despite our rethinking of more local forms of publication. But community is crucial.

I had a couple of early years, when I was on leave from Reading, at the Folger Shakespeare Library on Capitol Hill in Washington D.C. There’s a sign-in sheet which tells you who is there that day. And there’s tea, and gatherings. And in the course of a year I met an amazing amount of people. Some from England and Europe who were visiting – Tiffany Stern, for example, and Emma Smith – and almost all the names in North American scholarship were there, too. It provided an institutional infrastructure for meeting people and talking about work.

I also really enjoy collaborative projects, and para-academic collaborative projects. One of the things I’ve done in recent years is to set up a printing collective with friends, including Dennis Duncan and Gill Partington. We meet up every now and then with some friends and print something on a press I have in a barn at home. What we lack in technical competence we make up for in invention.

I’m a little sceptical about formalised grant-enriched collaborative structures and what they produce. I’m sure they lead to lots of material, but I still think the monograph written by one person is a really good form. There’s a reason it’s emerged and stood the test of time. But surrounding that, I very much enjoy collaborative engagements, particularly with people on the edge of academia: writers, artists, museum people, or printers.

INTERVIEWER

Do you build conferences or lectures into your research process? So as to give material an airing and get some feedback?

ADAM SMYTH

Definitely. For this Material Texts book, the cutting chapter was an article in ELR; the burning chapter was in a book on book destruction; and I gave quite a few talks about the printed waste stuff and the error material. So it all got an airing. It’s important to get that feedback.

I think writing for an audience that doesn’t already know the material is really good. I had a great formative period of teaching at Birkbeck in the University of London. All the teaching was in the evening and most of the students were older than twenty-five; the average age was mid-thirties. I was teaching classes to people who had done lots of interesting things in their lives and had been waiting, in some cases for decades, for a chance to do their English Literature degree. That was great, because it mattered to them. They weren’t going to put with flannelling or imprecision. If you used a word like ‘subjectivity’, they would shout out ‘what are you talking about? What does that mean?’. There was nowhere to hide, and it helped me take things back to first principles. I always find it most challenging meeting clever people who are not at all academic and who ask me about my work. You can’t say to them ‘I look at printed waste’, because they won’t nod and join the dots. That’s a ludicrous thing to say! You have to rehearse the stages of why it matters.

INTERVIEWER

How do you approach preparing a new Arden edition?

ADAM SMYTH

There’s a very basic question here about why we might need a new edition of Pericles. If you view these editions as markers of their time, of a particular intellectual moment, then they become both interesting as editions of Shakespeare in themselves but also as documents of editorial history. Arden editions mark the ideas of their moment. If you give up the claims for the definitive edition, and realise the poverty of that as an ambition, and realise that what you’re producing is an edition that marks its moment, then that both takes the pressure off and also makes it important to do.

Arden 3 Pericles is a great edition by Suzanne Gossett. But it’s also invested in its particular post-modern moment, wary of judgement or decision, committed to the benefits of uncertainty and doubt and everything being in play. And we’re not quite in that moment anymore. So I’m thinking now about what I want to emphasise. And one answer to that is that the first quarto of Pericles is a real mess. It’s as bad as anything that we would produce in our barn. The prose is verse, the verse is prose; there’s all kinds of errors. Previous editions have very rationally tidied things up. I want to try and do two things which I think are probably incompatible. On the one hand I’d like to produce an edition that, in the unlikely event of an A-Level student wanting to do Pericles, they could use this edition. At the same time, I’m interested in the errors and the bad printing, the prose that’s verse.

For example, when Pericles washes up on Pentapolis he’s met by three fishermen, who are these comic, bawdy figures who recover his armour and help him and are then forgotten. But in all seventeenth century printings – Q1 to 5, and the Third Folio – their speech is written as verse. Which is weird, because they’re these lower-class buffoonish figures. It looks as though their speech was meant to be prose, but they’ve been scrambled and set as verse. Normally, all other editions convert them into their appropriate prose, which makes sense. But it’s also true that everyone reading that play in the seventeenth century – which is its real moment of popularity – saw these fishermen speaking in verse. And that’s interesting. So I want to be both useful for the first time reader, but also accommodate the error-sensitivity that’s a marker of our moment.

But another interesting thing is that Pericles is having a real moment. It’s a play about migration, and people moving around the eastern Mediterranean, being separated from families and reunited. These concerns really do speak to our moment. There are two recent novels about it, too. One by Mark Haddon which is really good and one by Ali Smith which is quite good. In Haddon’s case it’s a retelling of Pericles, and in Ali Smith’s case Pericles is one text among many. But they both independently responded to Pericles as a text for our time.

INTERVIEWER

Certain stories resurface at moments when they’re needed. We draw something from them that helps us to mediate or understand our experience of the world at that moment.

ADAM SMYTH

There’s something brilliant about literature’s long-termness to do exactly that. Certain texts rise to the moment and then recede, but that doesn’t mean they’re lost, just that they’re available for the future.

~