paper Kingdoms 4: Adam g. Hooks

Field Notes: the archive of Adam G. Hooks, helpfully organised for a future material text doctoral scholar

Adam G. Hooks is a Shakespeare scholar and book historian based at the University of Iowa, where he is an Associate Professor who divides his time between the English department and Iowa’s Centre for the Book. He finished his MA at Georgetown in 2003 and secured his post at Iowa shortly before finishing his doctorate at Columbia in 2009.

I discovered Adam’s work through his first published article: a fascinating piece on how booksellers’ catalogues shaped the generic categorisation of early modern drama. Since then I’ve followed his writings on many other aspects of early modern book history and Shakespeare studies, most notably in his first book, Selling Shakespeare (Cambridge, 2016). In that compelling study, Adam explores a new methodology of ‘bio-bibliography’ — a form of life-writing that describes an author by tracing their presence in print, rather than by hunting down documentary evidence in archives, and which also features in Jason Scott-Warren’s new book on Richard Stonley. He also created the Shakespeare Census with Zack Lesser and runs his own website at Anchora, as well as being at work on several new projects, including the fourth Arden edition of Shakespeare’s Poems.

Adam and I spoke in May 2020 as he was laid up in quarantine and recovering from knee surgery. In conversation he is deliberate and thoughtful, speaking with dry wit and a keen sense of a responsibility to help other early career scholars. I am also entirely confident that he is the only person in the world who owns a copy of the STC, a copy of Schoenbaum’s Documentary Life, has a mohawk haircut, and is planning on a full sleeve of tattoos featuring the ornaments of the Shakespearean printer Richard Field. Prove me wrong.

Our conversation ran for about two hours and we covered a lot of ground, divided below into five areas. The first section (1.) Field Notes, includes Adam’s take on some current disciplinary trends in early modern studies including life-writing and the future of the case study. We then discuss Adam’s journey from (2.) thesis-to-book. I’m grateful to him for being so generous with his reflections on that process and recommend this section (along with the equivalents in other interviews) to early career researchers thinking through similar challenges. Next up are two broader sections on his (3.) Research and (4.) Writing practices, before finally we talk about his fascinating plans for the fourth Arden edition of Shakespeare’s poems in (5.) Editing Shakespeare.

Many thanks to Adam for his time in taking part and for supplying the images of his workspace that appear in this article.

(1.) Field Notes: Stationers, Case Studies, Life-Writing

INTERVIEWER

Adam! Thanks so much for doing this. Let’s start with the important things: what does the ‘G’ stand for?

ADAM G. HOOKS

It stands for Glen. My first name is a family name. The first person from my mom’s family who immigrated from Germany was named Adam and I was named after him. (And he was likely named after the biblical “Adam”). I asked my parents what the Glen was for, and they just thought it sounded good. I have to say, I don’t love ‘Glen’, but the ‘G’ has come in handy. If you Google ‘Adam Hooks’, without the G, you get a guy in Albuquerque, New Mexico with a rock band named ‘Adam Hooks & His Hangups’. If you Google ‘Adam G. Hooks’, you get me.

INTERVIEWER

You secured your job at Iowa in 2009, just before you had finished your doctorate, and a few years ago you successfully secured tenure. What has that meant to you?

ADAM G. HOOKS

I got my post in the year that the economy crashed — the last time — and a lot of the jobs were pulled. I had MLA interviews where the jobs disappeared after the interviews had been done. At the time, David Scott Kastan told me ‘You got the last job. Things will be different after this.’ And he wasn’t wrong. The job market has been dealing with that difference for the last decade.

I will say that having a secure position affects most things about your persona and character as an academic. I’m pretty sure that I waited till after I got tenure to get tattoos below the elbow, for example. Or to try out things such as this ill-advised (quarantine) mohawk [right]. You have to earn your place in a department and figure out the norms before you can fully relax (even though you never really relax), and all these things take energy, particularly when you have a book to finish.

Also: I try to use my privileged position to help students, colleagues, early-career folks — anyone, really. I love reading the work of others, and I love having the freedom to pursue new directions. And I actually enjoy the new administrative duties I’ve taken on, which allow me to have a greater impact on undergraduate education.

Adam G. Hooks: the quarantine version

INTERVIEWER

Much of your work engages in different ways with the influence that early modern stationers had on the literature we read. Are you still excited by stationers and what avenues do you see for future research in that field?

ADAM G. HOOKS

I do think that in some ways we are becoming exhausted by the case study approach, when it comes to stationers. By the time I wrote my dissertation, we were already asking whether the field was done with stationers because of Zack’s first book [Zachary Lesser, The Politics of Publication (Cambridge, 2004)]. We were already asking questions about the limits of the case study approach. As things stand, no-one has successfully theorised how to take a case-study approach and apply it to more general principles, at least in our discipline.

From a personal level I still enjoy working on stationers because there are still stories left that are untold. Some of them are on my hard drive; some of them don’t exist; some of them are being written by other people. I want to hear those stories. This work is about a basic recognition of human beings in the past who made available the things that we read and work with now. I would also say that I’m fascinated by biography and life-writing, and by finding alternate modes to tell stories about the literary record of the past. I’m still absorbed by stationers because they’re people with fascinating stories that fit within a critical or interpretive argument within our field.

At the same time, I also want to push myself to do something more, which is what a second or third project should do. Once you’ve finished the first book, you want to push yourself into territory that’s uncomfortable or unfamiliar in some way.

I’ll also say that over the last two or three years I’ve become more adamant about the affective quality of our scholarship. I desire to know more about these individuals. I don’t know what their desires were, but I want to know why we should pay attention to them, and I also want to know why and how the desires of past scholars have shaped the way we approach authors or stationers to see if we can find a different narrative to tell.

INTERVIEWER

What do you think the challenges are in trying to break out beyond the case-study with respect to early modern stationers?

ADAM G. HOOKS

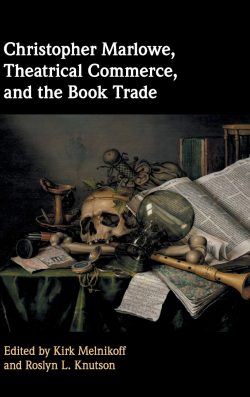

Some of the work here will involve breaking down and remaking our idea of what a ‘life’ or biography is. In my recent essay on Christopher Marlowe, for example, I was seeking to think through what a full-dress ‘bio-bibliography’ of Marlowe would look like. You take the biographical concerns that are standard in the field — in this case the field of Marlowe studies — and try to flip them to see what book history can tell you.

‘Bio-bibliography’ is a practice that dates back to the seventeenth century — it’s a methodology, a form of life-writing, that depends not on the documentation of external events, but on the books that were printed and published and attributed (&c. &c.) to a writer.

A life — whether of Shakespeare, or Marlowe, or whomever — depends on the afterlife in print. These were the earliest forms of authorial life-writing, and it’s a method that I find particularly compelling and productive, especially as a way of finding different narratives and telling new stories. So I feel this is a completely alternative mode of life-writing, and one that’s equally as valid as the more conventional biographies. Taking a bio-bibliographic approach makes the life porous; it blurs the boundaries and allows you to tell multiple narrative threads in the service of a name. We attach a personhood to that name, but really the resultant life is never only about one person.

INTERVIEWER

Ideas about affect, or a kind of critical selfhood, are becoming an increasingly prominent feature of early modern studies. Do you see this around you?

ADAM G. HOOKS

There are two institutional contexts here. One is that I see more and more the possibility of producing work that can be classified as a work of scholarship but also as a work of creativity. Normative definitions of fact and fiction are blending in an academic context. That’s been true with Shakespeare for ever: one example might be Graham Holderness’ Nine Lives of William Shakespeare [Arden, 2013], which reimagines key moments in Shakespeare’s life. But now we’re discovering that you can take similar methods that are partly research-led and partly fictional and use them to imagine the life of anyone. I try to stay attuned to the field of biographical studies or life-writing studies to think about what the role of narrative might be in all this.

But the second context is my department here at Iowa. We are made up of literary scholars, non-fiction writers, creative writers in fiction and poetry. And there’s a real sense that the future of the environment in which I currently live and work is about the crossover between what we would normally think of as fiction and scholarship.

I have recently been pushed to the limit of something I’ve always believed in. Which is that the kinds of work we do as book historians, and as bibliographers, and biographers is fundamentally interpretive and imaginative. There is no split. At least in some segments of the academy and certainly in popular publishing that seems to be a world that is alive and well and that people find attractive and instructive in various ways.

INTERVIEWER

What have you read recently in early modern studies that you’ve enjoyed?

ADAM G. HOOKS

I’ve been revisiting some things recently. For pandemic literature I’ve been reading Defoe’s Journal of a Plague Year and Albert Camus’ The Plague; Mary Shelley’s The Last Man. I will say I read through Frankenstein once a year, religiously. It helps me to work through knowledge production and obsession and desire. It’s written in the early nineteenth century and is set in the 1790s, when Edmund Malone is at work, which for book historians and editors is a moment of sea change.

I’ve learned a lot more about the plague in Renaissance London than I expected to. That’s in part through one of the best books I’ve ever read, Leeds Barroll’s Politics, Plague, and Shakespeare’s Theatre [Cornell, 1995]. That’s where my dissertation started. His work is astonishingly learned and wide-ranging: it’s at once rigorous, compelling and philosophically aware in ways that I think we’ve lost in early modern studies. He was there for all those debates in the eighties and nineties about the nature of the disciplines of history and English and his work reflects that sense of philosophical engagement. That may be the most influential book on me, bar anything written by David Scott Kastan or Jim Shapiro.

Looking ahead to teaching in the fall (online, alas) I’ve been working through Emma Smith’s This is Shakespeare [Penguin, 2019], Scott Newstok’s How To Think Like Shakespeare [Princeton, 2020]. I believe in working not thinking, but it’s a great essay/meditation on humanistic learning. And Shapiro’s Shakespeare in a Divided America [Penguin Random House, 2020], which I’m going to assign to my Shakespeare class. And I’ve been reading Shakespeare biographies written by women, which is a significant minority of biographies that exist, yet one with a rich tradition.

Beyond that, I’ve been reading a lot of Wittgenstein. It sounds very undergraduate of me to say this, but Wittgenstein has always been my favourite philosopher because of his emphasis on language and the ways in which that can be adapted to theories of narrative. I’ve also been re-reading Jason Scott-Warren’s Shakespeare’s First Reader [Penn, 2019], which I read for the press but am finding an amazing form of life-writing and book history. It’s just fantastic, and he has a way with prose that makes the evidence come alive.

Finally, I’ve also been reading a lot of biographies of scholars of bibliography and textual studies. People like Sidney Lee, James Halliwell-Phillipps, John Payne Collier, Frederick Furnivall, and Horace Furness. I’ve been re-reading parts of Joseph Quincy Adams, Hyder Rollins, and works about the Folger family. And I’ve also been reading the complete works of Alfred Pollard. I love Pollard! This grew out of an interest in Henrietta Bartlett because of our project the Shakespeare Census, co-directed with Zack Lesser. Pollard is always classed with W. W. Greg as a foundational New Bibliographer. But it turns out that Pollard was just a lovely man, and all the stuff we don’t agree with about the New Bibliography was pretty much all Greg’s fault. Pollard was just this very British gentleman.

~

Adam’s writing space in his home office in Iowa

(2.) Thesis-to-Book

INTERVIEWER

Can you talk us through your experience of finishing your thesis and transforming it into your first book, Selling Shakespeare [Cambridge, 2016]?

ADAM G. HOOKS

I want to acknowledge the precarious life and emotional circumstances that people find themselves in during this stage of writing their first book. I finished my dissertation in 2009 with three chapters that I felt were locked down, ready to go, and one chapter that was less so. This was back in the day when you could still get an academic job before you had finished your thesis. I cobbled that less-secure chapter together at the last minute and wrote an introduction that I always knew would not be the introduction to the book.

This is going to sound self-aggrandising, but the dissertation won the J. Leeds Barroll Dissertation Prize at the Shakespeare Association of America Conference — the only year since I began going that I missed, since my daughter was born during SAA — which was brilliant but somehow made me feel worse! The prize, not the daughter, obviously! I had no idea how to turn this thesis into a book, but then I was told I had a good thesis — so the challenge became, how do I make that into a good book? At the same time, I moved across country to Iowa, had a kid, bought a car, bought a house, and started my job. So there were a lot of personal, intellectual, and pedagogical challenges, and all the while, in the US at least, you have this ticking tenure clock in the background.

I knew Peter Stallybrass and his ‘Against Thinking’ piece that he wrote in PMLA. This piece articulates his idea that we should be working, rather than thinking. That’s always been my creed, especially for teaching. And yet, I over-thought the book. I was thinking too much and I wasn’t working enough. Alongside that, I also had to come to terms with my #foliofatigue, because I knew I had to have a chapter in the book on Shakespeare’s First Folio. I knew there was a bunch of work to do: I had to rewrite my loose chapter; I needed to rewrite the introduction. But I wasn’t sure how to do those things, and for a while I felt stuck between two different kinds of projects. One of those projects involved sending the thesis off as it was and publishing it as a skinny book, just a lightly revised version of this thesis which I had been told was good. And the other project involved radically revising the whole thing.

INTERVIEWER

What helped you decide between those two options?

ADAM G. HOOKS

The book should have been longer – there are draft chapters — on John Danter, for example, and on Pericles, which was my job talk — which remain exiled on my hard drive. But in the end, I decided – out of necessity, if not desperation – to structure the book as the thesis was structured, with four substantial chapters and a methodological and biographical introduction. It’s still a skinny book (appropriately, since I’m a skinny person!) but I am proud of it; in a way, the pressure to publish allowed me to overcome my own obstructionism, due to external demands of my personal and professional life, and finish the project. It’s a lesson I hope to impart to early-career scholars.

I was over-thinking, and I didn’t realise that I should just do what I always wanted to do. For me, it took a reader’s report from Cambridge University Press. The report pointed out in a very formal manner the thing that I had always believed: that the entire methodology of the book was encapsulated in the first and last chapter, this idea I had of writing a bio-bibliography. The report asked me why I didn’t just write that, rather than circling around it. After the report, I felt like I had a license to do what I had on some level always wanted to do. I re-wrote the First Folio chapter at enormous speed, and I wrote from scratch an introduction in about two weeks. It came out in a kind of divine fury and I sent it back off to the press.

INTERVIEWER

Could you talk about how you chose Cambridge University Press, and give any advice you might have about dealing with presses and editors for a first book person?

ADAM G. HOOKS

Why CUP? Well, on a certain level, I always knew I was writing a Cambridge book. The “competing and comparable books” section of the proposal was almost entirely made up of CUP books. It just made sense. And, while I didn’t personally know the commissioning editor (at the time, Sarah Stanton) I did know people who knew her, which was, in the end, helpful.

Do I have any advice for someone writing a first book? On the uplifting side, I would say to get to know the editor, if at all possible — it’s much easier if the editor believes in the project and actively wants it to succeed. This goes for series editors, who are generally scholars, and press editors, who are generally publishers.

But, do not expect it to be a smooth process — if it is, fantastic! But it’s not always easy. In my case, Sarah was in the process of retiring, and I was passed around to a multitude of assistant editors and project managers. It was frustrating, and the book got kind of lost for a while. It was published on time, though, and I got tenure because of that, so I’m definitely not complaining. Was it an ideal process? No. Was I naïve and did everything work out anyway? Yes. I will say, however, that I will never, ever again publish a book with a press that charges a hundred dollars for it. This is a basic ethical, accessibility issue. Saying this out loud is my responsibility as a tenured professor, and as a human being invested in an intellectual life.

INTERVIEWER

How long did it take you from completing your thesis to sending off a manuscript to Cambridge University Press for the first time?

ADAM G. HOOKS

Longer than it should have! Writing for me is a long and frustrating process and I set really high standards for myself that I’m not willing to compromise. That’s great, but it also extends my writing process. My goal is to set a well-crafted paragraph next to another well-crafted paragraph. Not that I’ve always done that. But that’s the goal to keep in mind and it takes extra work.

After I sent the final proofs back to Cambridge I said to a friend: ‘Okay, so now I know how to write a book.’ So then the question becomes, how do you take that knowledge and self-awareness and try to write another one? I think when writing your first book, you don’t understand what it is, or what it could be, or what it should be, until you’re finished with it. I don’t mean that as a cop-out: I believe that our work and our lives are embodied experiments.

INTERVIEWER

What did you learn from writing your first book that you carry forwards into your current writing projects?

ADAM G. HOOKS

I’m still trying to articulate and learn from the lessons of writing and publishing a first book. I now understand that the argument must be the centre of the book — not the details, not the case studies, however much I love those stories. There must be a collection of appealing stories, don’t get me wrong — but an ‘academic’ book must clarify and repeat a central argument, whether it’s methodological or theoretical. It must be ‘proof-of-concept’ rather than exhaustive, which is one way to solve the ‘case-study’ problem. But I also learned that I don’t necessarily ever want to write for a strictly ‘academic’ press or audience. It’s the teacher in me, the public-school kid in me, that wants and needs to reach a wider audience, even as I want to address my colleagues around the world.

It’s been interesting to advise PhD students how to write their dissertations and to manage the process of moving the dissertation forwards. With my particular population of graduate students that tends to involve questions like: do you want to turn this into a series of articles? Or do you want to do an online project, or a monograph? Not all of our students want or need to choose the monograph. Producing a first book is hard! It can be frustrating and is stressful. But once I gave myself the green light, I finished off the book very quickly.

INTERVIEWER

What helped to give you that green light?

ADAM G. HOOKS

The reader’s report helped. I got two very divergent reader’s reports. One was very helpful and it gave me an external license to do the thing that I was refusing to give myself an internal license to do. The other one was more tricky. It was someone who was not strictly an early modernist but from an adjacent field. It was the classic ‘reader number two’, who had a list of errors or problems that needed to be fixed, with little sympathy for the central argument and goal of the project.

That second report actually reawakened the way that I think most theses start, which is with the student acknowledging to themselves: ‘I think someone is wrong, and I am going to fix this problem’. That’s how I started my dissertation: I think x is wrong; now how do I find a compelling project that allows me to do something creative and allows me to make an impact in this conversation? The revising process whereby I rewrote parts of my manuscript and sent it back to the press felt like a more advanced version of how I started my thesis in the first place: I thought someone else was wrong. Of course, that thought itself is always wrong. That’s what Jim Shapiro in one of the more significant elevator rides of my life told me. He was struggling with something, and he said, you’ve got to just think exactly the opposite of what everyone else thinks. And that will be wrong. Conventional wisdom is conventional for a reason. But putting yourself in the opposite perspective will provide you with questions to ask that will be productive. I don’t believe in the language of originality, but those questions will be productive and will lead you to something of value.

INTERVIEWER

Having finished your book, what advice would you give the version of you who was just starting out on the process of transforming thesis into book?

ADAM G. HOOKS

Some of this is going to sound like I belong on the Oprah channel. Despite all the external modes of approval, I still felt vulnerable. And I didn’t recognise at the time that vulnerability is the condition of possibility for courage — in fact, it’s what allows one to articulate your critical concerns, because making your work public makes you vulnerable, but it also makes you brave. First books are particularly prone to this — it’s not just a book project, it’s your thesis, which has determined this all-consuming academic identity that you possess. So I would tell myself to be more trusting, to have compassion for my self, to connect my work to other colleagues dealing with similar issues.

I also think that derives in part from my graduate training which had me in between these two different worlds. There’s hardcore bibliography and book history, and then, at least at the time, there’s literary criticism or literary interests. I was always told that I had to straddle those worlds; that you can nerd out as much as you want, but it has to have some critical purchase for a wider audience. So I was always forced to think about a wider audience, which was exactly the right thing to do.

But I always knew that the danger of that is you never please any one particular crowd. And, being young, I didn’t realise that the only scholar I really had to please was myself. So if I had a bullet point for myself, I would say: be compassionate, to other people and yourself; be willing to be vulnerable, by being willing to take the criticism that you know will come.

As an example, let’s take my Andrew Wise and Thomas Playfere chapter in my book. A version of this was also in the Marta Straznicky collection Shakespeare’s Stationers. That chapter has always been emblematic of both my best strength and my greatest weakness, which is that I produced a book history account of ways in which we can use this particular publisher — Andrew Wise — as a locus to understand how literary and commercial values work. But at the same time, I’m trying to write about literary style. Of all the things I’ve written, that’s the piece that I’m most proud of, because I did a hell of a lot of research on Thomas Playfere! But I also understand that it may not work within the disciplinary boundaries in which the chapter was first conceived. It’s the chapter that determines whether a review of my book (or Marta’s) is positive, or negative. It’s an easy target for the bibliography crowd, yet my explicit acknowledgement that I’m telling a story fits within the historicist and critical crowd.

INTERVIEWER

Could you say more about what you feel didn’t work in that chapter?

ADAM G. HOOKS

I knew that I needed to be able to produce a literary reading of a Shakespeare play in my thesis, quite simply because of the demands of the genre and the demands of the job market. So I spent a really long time trying to come up with a way to approach this material that would be both true to the book historical methodology, but also would show that Richard II is my favourite Shakespeare play! That’s sometimes the knock that bibliographers get, isn’t it: that they don’t care about the text. But in fact I care about both.

So I went through a lot of iterations of that chapter in graduate school. Those alternative approaches began with: here are some ways that ideas about mourning and tears are characterised in Thomas Playfere’s sermons and in Richard II. And the work eventually veered towards arguing that Andrew Wise enables us to explore possible connections between Playfere and Shakespeare, treating the publisher as a locus of interpretation. I wanted to ground something in some kind of historicism but at the same time challenge and question the positivist aspects of that historicism.

What does that mean? It means that I don’t claim that Andrew Wise thought the same thing about Shakespeare and Playfere that I do — I tried to make the case that this view was plausible, but not demonstrable. It’s probably true to say that I know more about Andrew Wise than most people on the planet at this point, but that’s still pretty slim knowledge. I don’t know why or how he decided to publish Shakespeare and Thomas Playfere together, but I can tell a good story about how that might have taken place and what its consequences might have been and I can tell that story in a way that is intellectually, theoretically, and philosophically responsible.

There’s an abundance of proper historicist research in that chapter — but I’m not positing any causal effect here. I like to say that book historians interpret things as well, it’s just that we have to do more homework first. I did my homework. I made an argument. It may not be right, whatever that means, but if you disagree, please do me the courtesy of disagreeing within the terms of the argument. That’s what generous readers do.

~

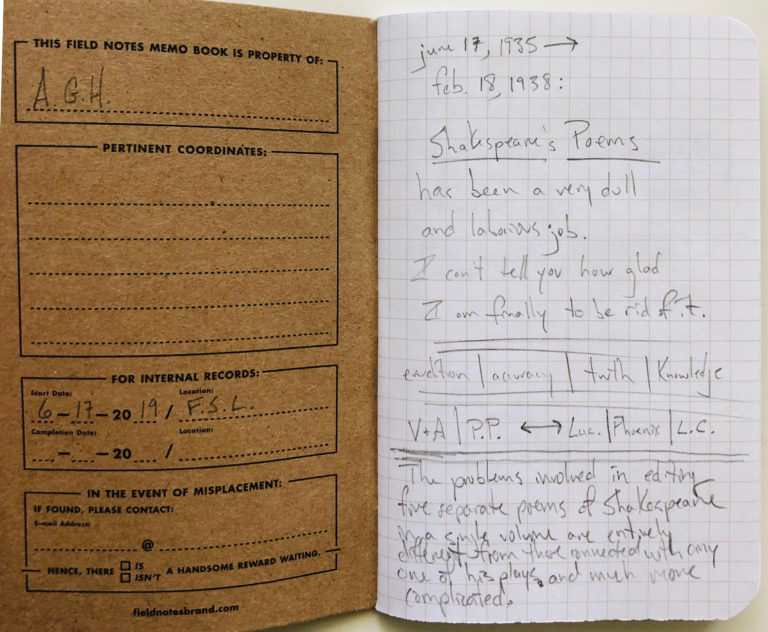

‘If I’m starting a new project I have to write by hand’: opening from Adam’s Folger notebook from last summer

(3.) Research

INTERVIEWER

How do you typically begin a research project?

ADAM G. HOOKS

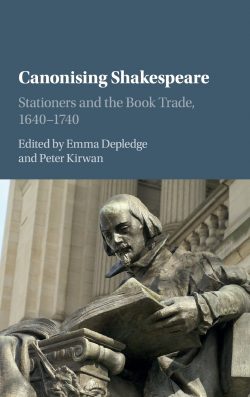

I have lots of ideas at any one time. Too many ideas, in fact. My hard drive is filled with ideas that haven’t seen publication. My recent essay on Lucrece [in Canonising Shakespeare (CUP, 2017)] is a good example of that — this was a piece of work that began about a decade and a half ago. It was part of my Master’s thesis — the final section, which became my writing sample for PhD programs. It was the first piece of book history I ever wrote.

It went through endless versions in various conference seminars and presentations. I knew what I knew, but I also knew what I didn’t know, and I resisted doing the necessary work for quite some time (fifteen years!). But I was very fortunate to have editors who believed in and wanted the essay, and they helped me immensely — thanks, Pete and Emma! I learned a tremendous amount about Royalist politics in mid-seventeenth-century England, to pair with my focus on stationers and book history. And this all started because when I took the M.A. Research Seminar at the Folger, they would only allow me to see Wing books (at least when it came to Shakespeare) so I was able to see multiple copies of the 1655 Lucrece. It was life-changing.

Anyway. I often start a project by wanting to find a story. Though I don’t push on anything and to be honest it feels more like stories come and find me. But you have to be open to receiving and acknowledging those stories.

INTERVIEWER

Can you say any more about that? What does that look like practically? Do you keep a Word file of prospective things you’re interested in?

ADAM G. HOOKS

I have a complex array of digital and analogue resources that I rely on for ideas and research. In terms of my digital practice, I might see something on the internet that triggers my interest, and I’ll follow the link and save it to Pocket so I can engage with it later. If it seems necessary I’ll later export that to Evernote or Zotero and file it away in the appropriate place on my hard drive. At the same time I have Scrivener open most of the time. For things like taking notes from printed books, I’ll use Scrivener or EverNote.

Alongside that, I have an addiction to and/or obsession with Field Notes notebooks. I use their pencils, too: the Number Two, cedar, bonded lead. I’ve actually visited their headquarters in Chicago — that’s how much of a nerd I am about my meta-research process. I have a wooden box that is branded with Field Notes and each book is about pocket size, which initially worked for me because I grew up on a farm in the middle of nowhere, and I used to see my grandfather and my father use these little books. They were actually account books, really, although I’m saying that because I’ve just been re-reading Jason Scott-Warren’s new book Shakespeare’s First Reader.

INTERVIEWER

Could you talk about the process of moving between research projects? For example, when you finished your first book, how did you approach committing to your next idea?

ADAM G. HOOKS

Multi-tasking is not for me, even though I have ‘too many ideas’ at any one time. I find it difficult to bounce directly between different projects, since for me any given project can be all-consuming. That said, I usually have several irons in the proverbial fire at the same time, but the goal then is to find a way to make connections among the projects so that I can stay productive.

Some of my larger projects began as conference presentations, which provide a nice deadline to complete at least a preliminary version, even if it’s just a ‘proof-of-concept’ with one or two examples. But I will say that, with the freedom of tenure, I took a lot of time to just read widely in the field of early modern studies. That’s inventio at its finest and most pleasurable: reading, taking notes, trying to synthesise, letting my mind wander to see what new connections or stories might develop.

That’s very much how my ‘Shakespeare’s Bones’ book project started: I was invited to give a talk in Stratford-upon-Avon, so of course I wanted to (metaphorically, at least) disturb the bones of the town’s most famous resident, so I wrote a paper that began with the epitaph on his gravestone, and circled out to all sorts of interesting marginal manuscript texts in the seventeenth century. And now, after a couple of years of reading and note-taking and pondering and writing, I feel like I have a handle on what this project might become. I’ve learned not to put too much pressure on myself — you simply cannot force an idea. And if you do, the book won’t be as successful as it should be. That’s a lesson that the thesis-to-book process taught me.

INTERVIEWER

You work a lot with primary materials in rare books libraries and archives. Do you have any tips for how to make the best use of your time in such places?

ADAM G. HOOKS

Skip lunch! Just kidding — although I am known to focus for very long stretches of time in research libraries, especially if there won’t be an opportunity to return anytime soon. So the goal is to accumulate as much material as possible, with the aid of my iPhone camera and a pack of Field Notes, and to worry about organising and sorting through the material later, whether that’s straight away after the library closes for the day, or upon returning home. You need time to play in the archive, even as you also must be aware that your precious time is limited. But you have to have a system of organisation. That’s absolutely crucial, especially when working on a big project like an Arden edition.

INTERVIEWER

What does your research community mean to you? Either at Iowa or more broadly those in your field internationally.

ADAM G. HOOKS

It means everything to me — this is not the kind of work you can accomplish alone. Yes, of course one must spend a long time by yourself, working and writing and revising, something that’s been exacerbated by the pandemic quarantine. But you simply cannot be successful unless you find a community of readers and writers to share your work with, starting early in the process. Does this make you vulnerable to criticism? Yes, of course! But after all, vulnerability should be a source of strength.

There are very, very few early modernists at Iowa, so my community here in Iowa City — particularly at the Centre for the Book — is nourishing in a more holistic way, rather than an engagement with specific intellectual aspects of my specialised work. The Newberry Library in Chicago has done a fantastic job recently in fostering communication and connection among consortium members, and I’ve been lucky to either participate in or direct some of the programs there. It’s my fellow Shakespeareans and book historians, though, that are the lifeblood of my work — something that quarantine has made all the more important, as we are physically isolated but perhaps more social, at least virtually, than ever. At least that’s been my experience.

Because I’ve been fortunate to have a robust network of colleagues and communities, I also try to pay it forward for graduate students and early career scholars. That’s what tenure is for. Kastan has always said that he is most proud of his graduate students and others who he has mentored over the years, and I very much believe in that.

~

(4.) Writing

INTERVIEWER

What does a typical writing day look like for you?

ADAM G. HOOKS

My best writing used to happen in the late morning to mid-afternoon. By about four or five o’clock, that’s usually it. In graduate school I’d be tired by that point; in parenthood there’s a child that needs to be taken care of. I keep in mind a daily deadline of somewhere around cocktail hour.

But now things have changed a little, perhaps because of the pandemic. I get up very early in the morning and focus particularly well in that time. So on a good day that might be 6am but on a bad day that would be about 4am. This only started happening once the world shut down, but it’s radically altered the rhythm of my work day.

I guess the more generalisable point is that unless I am working on a very close deadline — in which case I’ll go into a kind of furor poeticus — then my writing is a slow process. During term time, for example, I find it almost impossible to write.

For a while writing became easier once we retreated to working from home, because there was a very clear demarcation between my home office, which I treat as my writing space, and my work office, which is my teaching space. Not to say that those don’t bleed over, but having two offices made it easier to get some writing done. I also mark out time in my Field Notes calendar to either prepare for writing or do writing.

INTERVIEWER

And you write on your computer?

ADAM G. HOOKS

Yes. Although if I’m starting a new project I have to write by hand, using my notebooks and a pencil. This is in part because it’s how I started my thesis — scribbling notes on notepads. I take a lot of primary research notes in my Field Notes books. And will use the same notebooks to produce ideas.

I’ll do a later stage of the actual research on my laptop. What I mean by that is things like marking up PDFs on my iPad, or typing out the notes I’ve made relating to a particular printed book. But when it comes to the idea part, and the bigger questions like: ‘what do I want to do with this material? Where is it taking me?’ then I have to work by hand and go back to the physical notebooks. In both starting my doctoral thesis and finishing the book, I really relied on physical notebooks to help organise my ideas. There’s something heinous about sitting down to write with a blank word document. That’s why I tell my students to work, not think — it’s all about inventio.

I also pace a lot when I’m writing. And I’ll go outside; I would not have finished my book if I didn’t take daily walks, multiple times a day through the park near where I lived at the time. I just took those when it felt right, but I had to take them every day. I need to be mobile. The lack of mobility and its impact on my productivity is the keenest pain I feel from my recent knee surgery.

I noticed in the Adam Smyth interview you asked about fonts, and Adam mentioned that he had been writing in Calibri. I despise Calibri! But I write my first drafts always in Calibri because of that feeling. I want to get to the point where I can go back to Garamond or to Cardo or even to Bembo Book, if I’m feeling fancy and inspired.

‘The lack of mobility is the keenest pain I feel from my recent knee surgery’: writing amid recovery

INTERVIEWER

So the change in fonts for you signals a certain stage of the process?

ADAM G. HOOKS

Yes. My process goes something like this: I start with handwritten notes for ideas or a structure or just some gnomic utterances, then to primary research notes and transcriptions on the computer, then to writing first in Calibri and then being revised and transformed into polished Garamond, or some other properly serifed font.

If I’m reading a book that I value a lot, perhaps because it’s something I revisit often or if it’s something new and exciting that I engage with, then I’ll write notes by hand, not only in the margin but on a notepad or a notebook, and then I’ll put those pages into the book itself. And then, at some later stage, I might copy it into my laptop. But there’s something about the physical artefact and the way that my brain matches up ideas with those artefacts that means I find it helpful having everything together.

INTERVIEWER

When is the right time to leave behind your physical research notes and begin writing?

ADAM G. HOOKS

When I actually need to start forming prose rather than ideas! I find the research pleasurable and extraordinarily easy. The writing part and the finishing part is the hardest part for me.

INTERVIEWER

At what stage of the writing process does most of your work happen? Do you sit down and labour over your plan and then know where a certain paragraph is going to go, or are you someone who discovers and thinks through what they are saying as they write?

ADAM G. HOOKS

Writing is a process of translation for me. When I’m typing in Calibri, I’m trying to translate the long cogitations and gestations my ideas have undergone in my mind. So for the most part, the work of thinking happens before I sit down to write, although I do discover new things when I start writing. I wouldn’t say I’m the kind of person who thinks through the writing; I feel like it’s a process of translation. That’s why I use multiple fonts: that first layer, that Calibri layer allows me to work on a process of translation where I’m not thinking about prose style at first. Then I can come back and do the extra work of trying to shape it into good prose in the Garamond.

I’ve been told by others that, while I have a long gestation period, when I get down to it I actually write very quickly. It never feels like that to me! To me writing can feel like murder. It’s terrible and it takes for ever and it’s painful! But I’ve had people who know my process say that I in fact write very fast.

INTERVIEWER

What do you think explains why your sense of your process is different from how others have seen it?

ADAM G. HOOKS

I’m not a person who gets up at the same time every day and works for two hours. I don’t write every day. I’m incapable of doing that. I have to be in the right mindset. That doesn’t mean that when I do sit down and feel that everything is perfect then I can write brilliant things. It’s just that my process is multi-layered: I have to read, I have to take walks, I have to let things percolate. Early in my career deadlines helped me be productive. Now it’s more about my own ambitions for what I want a piece or book chapter to look like.

But there is an element of fury happening when push comes to shove and you really need to write something. Such as the revised introduction in my book. I had been harbouring these ideas and scraps of knowledge in my head for years, and it just came pouring out. Perhaps that’s the moment that people see more. But that also meant that, at the time, my family had a rough go of it because I was up for twenty-four hours a day at some points typing things out.

INTERVIEWER

How important is style in your writing? Do you have any particular rules around using imagery, for example?

ADAM G. HOOKS

I don’t think of myself as a fantastic prose stylist, but style is extremely important to me and my writing process. There is certainly an ‘Adam G. Hooks’ style, even if it’s just a penchant for alliteration and parallel constructions like chiasmus (which has the benefit of being a rhetorical figure that’s fun to pronounce). I also read other scholars’ work for style; I had to revise my thesis, in grad school, to take out all of the unconscious citations from Shakespeare and the Book which I had absorbed, and which just became part of my intellectual vocabulary.

INTERVIEWER

Do you re-write and edit very much?

ADAM G. HOOKS

Definitely. I wish I was more efficient at re-writing. It’s easier for me to write something new than to edit something that already exists, which means I end up doing quite a lot of re-writing. I constantly edit myself as I write. I’ll spend two hours in the morning writing a sentence or a paragraph that I’ll scrap by the end of the day. It’s a cliché of writing, but that’s just how it is.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have any writerly superstitions, habits, or rituals that help your productivity?

ADAM G. HOOKS

I’m very particular about my space. Perhaps that’s a Midwesternism. I’ve always been a home office person and I’m very happy with the aesthetics of my home workspace. I have a comfortable chair and a decent reference library that — for someone on my state-school salary — can mimic as closely as possible the reference library of the Folger’s reading room. Far more limited, of course, but I’ve got my STC and my Greg and my Schoenbaum. I like having things at my fingertips and enough space to spread it out.

I drink a lot of herbal tea, and I generally do need to get out and walk. At the moment, with us all working from home, I find I’m struggling to keep my writing and my work compartmentalised from my life. I think there’s a necessary emotional and psychological distance that’s a factor of environmental and physical distance. I can do work on trains or planes, but I can’t write.

~

(5.) Editing Shakespeare

INTERVIEWER

You’re editing the Poems for the fourth series of the Arden Shakespeare. How did that come about?

ADAM G. HOOKS

The Arden Four Poems is a massive and unwieldy project. I’m both thrilled and terrified by it. Everything except the 154 sonnets is now my responsibility, which is daunting. The project came about because the General Editors of the series asked me to give them a ‘top five’ texts that I might be interested to edit. I did that and included the Poems, which is always the last thing to be assigned in any complete works series. I think seeing that title on my list encouraged them to ask me to go ahead, and I agreed to do it.

I also have a book project in progress that focuses on Shakespeare’s ‘bones’, starting with the epitaph on his gravestone. I see the various epitaphs and epigrams attributed to Shakespeare in the seventeenth century as a distinct genre that shouldn’t be shunted off to an appendix. So that helped convince the editors that the Poems were a good fit for me. Along with the fact that, you know, I’ve been working on Shakespeare’s poems in various ways for my entire career.

Editing the poems isn’t about producing an edition of any one thing, it’s about producing an edition of a corpus of things, which makes it completely unique within the Arden series. Within that, I’m finding that so far I’m more interested in the marginal work than the two long narrative poems. But that’s also because I’m at the beginning of the work, and the idea of editing two long poems, which are each as long as a single play, is a little intimidating. For me, Lucrece is by far the scariest of all the poems: it’s wonderful and terrifying and very long. But I love that poem’s unrelenting speed and force, evident in each of the stanzas.

INTERVIEWER

What are your main interests for the Arden Four Poems? Do you have a sense yet of what it will look like?

ADAM G. HOOKS

At this point, it’s been nearly two decades since Colin Burrow’s doorstop edition of the poems [The Complete Sonnets and Poems (Oxford UP, 2002)]. That’s my go-to edition, and probably will continue to be after I produce my own, to be quite honest. But in that time there’s been a recovery of Shakespeare as a poet. I’m not sure I would have agreed to take it on if it were not for the fact that the poems have now had enough critical attention in the last two decades that you can do some really funky stuff with them. At least, that’s what I’m aiming for. I think I have a different sense of the canon and have been working on these poems for a long time, in various ways, and would like to be able to, if not quite redefine, then at least radically reorganise the canon of ‘Poems’ for Shakespeare.

INTERVIEWER

Can you tell us any more about what that will look like?

ADAM G. HOOKS

Well, as book historians we know that the contingencies of book production will always shape the end product, and who knows what will happen at the end of this particular very long-term project. But I would love to attempt a book historical edition of the poems.

A few thoughts here. Firstly, nobody has ever theorised editing Shakespeare’s poetry. All of the editorial theory is for the plays. That lack of theoretical attention on the poems dates back to before New Bibliography. That lack of theory is interesting in and of itself: how do you edit a poem in ways that don’t necessarily adhere to all the principles of editing plays?

My ideal edition would start with Venus and Adonis, but would then move to The Passionate Pilgrim, because you can’t understand those two works separately from each other. Then I would have the poem that we call the Phoenix and the Turtle. So I wouldn’t hive off those poems into a ‘minor pieces’ section at the back. If I was able to do my ideal editorial chronology of Lucrece, I would wait to place it at 1616, where it acquires the title The Rape of Lucrece. There are a few reasons for that. Firstly, I don’t feel as though, in 2020, we can responsibly pair Venus with Lucrece. When the poems originally came out, Lucrece was thought of as an erotic companion piece to Venus and Adonis, but now I just don’t believe that’s a responsible approach, especially for an edition that might end up being used in classrooms.

But secondly, establishing a later chronology for Lucrece also shows us that this is the Shakespeare work that has the most editorial intervention in the seventeenth century: the chapter headings, the emendations; the contents leaf; the typography — it has far more clearly editorial alteration than any of the plays. And I want to incorporate those alterations somehow, rather than producing another edition of the poems that includes the same works in the same order with the same authorial trajectory, under the same rubric that Shakespeare authorised the poems and so they aren’t editorially interesting. I don’t think we need to retain all those ideas. I do book history and bio-bibliography, so here is a chance to offer an alternate construction of Shakespeare’s career by paying attention to these alternative and later editions of the poems.

INTERVIEWER

It’s exciting to think that the banner of Shakespearean authorship sanctioned by the Arden series might be expanded to include other agents, like those who tinkered with Lucrece for the 1616 edition.

ADAM G. HOOKS

We’ll see. Each Arden editor is assigned one of the General Editors. Tiffany Stern is the General Editor who has been assigned to me, and she told me they would tell me if I needed to pull back. All the General Editors, and I think the editors at Bloomsbury, were eager that someone had expressed an interest in the Poems. As I say, it’s always one of the last volumes to be assigned.

INTERVIEWER

Why is that? In some ways the Poems feels particularly exciting, because it’s interestingly disaggregated and various. It seems, from the outside, to be a particularly rich editorial project. But perhaps another way to frame that is that it’s an equally big commitment.

ADAM G. HOOKS

Yeah. It happened not long after I got tenure, and at the time I thought: ‘I really am the Richard Field guy’. I wrote a chapter about that printer; it was with him that my dissertation project started, and now I’m stuck with the guy.

INTERVIEWER

Not to hammer this home, but do you not have a tattoo of Richard Field’s woodblock device?

ADAM G. HOOKS

It’s right here on my arm. I also have the ‘threnos’ pattern from ‘The Phoenix and the Turtle’ which was also printed by Richard Field in 1601. I think my best bet here is to opt for a sleeve of Richard Field ornaments.

~