paper kingdoms 8: Zachary Lesser

‘For a very long time I had no idea where the work I had gathered for this book was going’ – Zachary Lesser

Zachary Lesser is the Edward W. Kane Professor of English at the University of Pennsylvania. He earned his doctorate from Columbia before securing a job at the University of Illinois in 2001. After moving to Penn in 2006 he worked his way up through Assistant and Associate through full Professor and was elected to a chair in 2020. His third monograph, Ghosts, Holes, Rips and Scrapes: Shakespeare in 1619, Bibliography in the Longue Durée, was published by the University of Pennsylvania Press in 2021.

Speaking with Zack about his research and writing process was a particular privilege for me because I well remember the impact his first book made on me as a graduate student. The appeal of Zack’s particular brand of book historical precision and literary critical insight was demonstrated by the success of Renaissance Drama and the Politics of Publication (2004), which won the 2006 Elizabeth Dietz Award and inspired lots of subsequent work by figures like Marta Straznicky, Adam G. Hooks, and Amy Lidster among others. My own forthcoming book about the First Folio is in no small way a response to Zack’s creative handling of stationers and playbooks.

Since his first book Zack has written and created a tremendous body of work. His writings have sparked seminal debates about the popularity of playbooks; about fascinating features of typography and print culture more broadly; and about editorial theory. His new book radically overhauls what we thought we knew about the mysterious and semi-Shakespearean collection of plays published in 1619 and known as the Pavier Quartos. We cover some of these topics below, but something we didn’t talk about was the fact that Zack has also co-created some of the most widely used digital resources in early modern studies. As graduate students, he and Alan B. Farmer created DEEP; more recently he and Adam G. Hooks created the Shakespeare Census, which is enabling all kinds of interesting copy-specific work.

Our conversation below is in four parts. In (1.) Ghosts, Holes, Rips and Scrapes, we discuss Zack’s new book. In (2.) Early Career Life, Zack reflects on his doctorate and first jobs; part (3.) Writing Habits gets into the weeds of writing, collaboration and academic Twitter. I found his comment that ‘The thing that you least want to write about in your chapter or book is probably the thing you most need to write about’ strikingly resonant. Finally, given that Zack is one of the General Editors of Arden Four, we spoke briefly about his vision for editing that series in (4.) Editing. Many thanks to Zack for making time to talk and for supplying some images of him and his workspace.

(1.) Ghosts, Holes, Rips and Scrapes

INTERVIEWER

You just published Ghosts, Holes, Rips and Scrapes, a book that overhauls our knowledge of the Pavier Quartos. Congratulations! Are you happy with the project?

ZACHARY LESSER

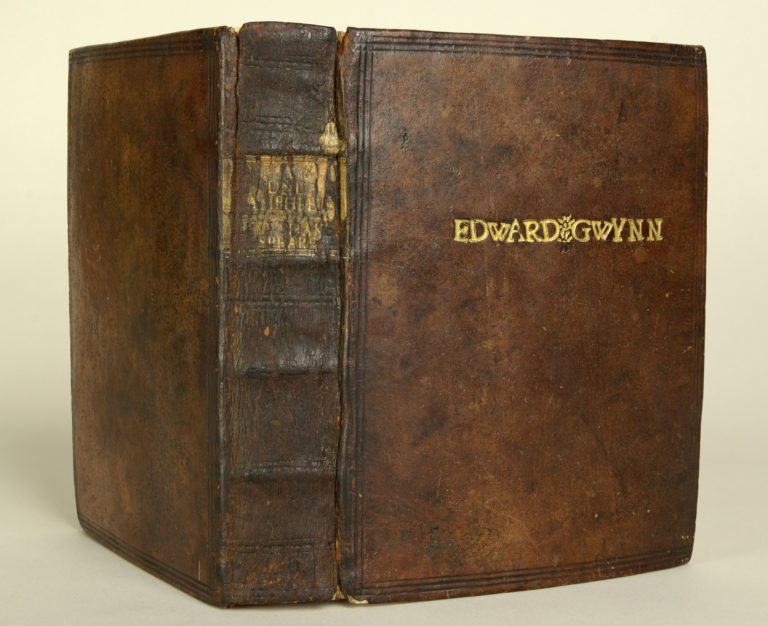

Thanks! Yes, I’m happy with it. I was pleased the press agreed to print the images in colour–some of the evidence is barely perceptible in black and white. I’m also glad that book was published in collaboration with the Folger Shakespeare Library because it began from Edward Gwynne’s copy of the Pavier Quartos.

INTERVIEWER

Your first two monographs both won the Elizabeth Dietz award. No pressure.

ZACHARY LESSER

Well, the first two books were much broader! They weren’t really bibliography; they were history of the book. One was about Hamlet and the other was, very broadly, about Renaissance drama. I think both probably had more appeal to our field in general. This one is a little more narrowly tailored! If you’re not particularly excited about Shakespeare you might not necessarily care about the Pavier Quartos.

It’s a little hard to gauge the audience for this book, partly because it involves some technical bibliographic work. This project might also appeal to non-academics, because of the mystery aspect, but perhaps less to early modern studies in general.

INTERVIEWER

The Pavier Quartos do have a broader appeal. There’s a Wikipedia page on the ‘False Folio’ for example. And the scholarship around the collection has an intrinsic narrative shape, which, as you point out in your book, forms a kind of detective story.

ZACHARY LESSER

Yes. I briefly thought about writing this book for a trade press. If you think about books by Shakespeareans that have appealed to a wide audience, they tend to be either biographies or narrative-driven stories. And I do think there’s a story here for a general audience. I think bibliography readily appeals to a wider audience because of its forensic qualities, which people are familiar with from TV: someone tries to figure out who wrote a ransom note or whatever.

But in the end there was too much I wanted to say about the disciplinary history of bibliography, not to mention the broader meditation of the book on the limits of the discipline–on what bibliography can tell us and where it falls short. That story I don’t think is interesting to a broader audience.

Edward Gwynne’s copy of the Pavier Quartos. Image: Folger #165225 of Folger STC 26101 copy 3

INTERVIEWER

Has the way you think about the audience for your writing changed over your career?

ZACHARY LESSER

When I was writing my first book, I think the audience I had in mind was really my dissertation committee. It’s hard to imagine beyond that for a while after grad school, I think. I am interested in the challenge of translating the kind of work I do for a much broader audience, but I keep failing to actually do it.

INTERVIEWER

The Pavier Quartos is a complex topic. You organised your project around three different types of evidence, each of which forms a chapter in your book: ‘ghost’ images; stab stitch holes; and imprint-tampering. How did you decide on the structure and organisation of this book?

ZACHARY LESSER

For a very long time I had no idea where it was going. Writing Ghosts, Holes, Rips and Scrapes was a totally different experience for me from my previous books, because it grew out of the research and from a series of talks. I must have given ten or fifteen talks over five years, all of which happened without a clear sense that this would ever be a book. Shaping a project through talks was interesting as a writing method and proved useful for me.

INTERVIEWER

Why is that?

ZACHARY LESSER

The talks I write tend to be conversational and narrative and I think the book reflects that. As I continued the research–which basically meant going to see as many copies of these things as possible–there was always a chance I’d find something that would require me to rethink everything. Meaning I had to revise the talk for the next time.

That process of being forced to revise my thinking became part of the book itself, and exposed a key question in the book: what are we seeing and what are we not seeing? What did the New Bibliographers miss through their own ideological presuppositions and what are we unable to see? So the theoretical reflections on the limits of bibliography in this book emerged from my process of rewriting through research.

I had no idea what I was going to do with the work. For a long time, I imagined it would be a long essay in The Library, because that’s where Greg’s essay was published. Then one day I had the most clichéd experience of being in the shower and the table of contents came to me, with the book organised by the different types of evidence. Not that I discovered them, but these are three kinds of bibliographic evidence that had not been used much, or even known about. The New Bibliographers seem not to have been aware of them at all.

INTERVIEWER

It sounds like writing this book was a different process from your previous books.

ZACHARY LESSER

None of my other books have come to me in the shower. My first book emerged out of a dissertation. That’s a ten-year process of thinking, intensive drafting and re-writing. Whereas for this book, I researched in libraries for about five years and wrote all these talks before I wrote anything for the book. Then I sat down and wrote the book in about two months. The process felt more like the way that a scientist writes up their data. I had all the material and wrote it one stretch, from start to finish, from page one to the end.

–

‘I researched in libraries for about five years and wrote all these talks before I wrote anything for the book.’

–

INTERVIEWER

The book gestated for five years as you gathered material and gave talks. Its publication seems like a compelling argument against the prevailing culture of academic haste and ‘publish or perish’. Is this a mode of scholarship that is threatened at the moment?

ZACHARY LESSER

Absolutely. I think bibliography in general is threatened as a result, because it typically requires a long time spent gathering evidence, slowly and patiently, before you see any ‘productivity’ out of it. If you look back at some of the landmark and truly monumental works of bibliography from the early twentieth century, it’s absurd to imagine them being written in today’s academic culture. I’ve got tenure, and I work at a wealthy university that enables this kind of research through funding, sabbaticals, and so on. Without those privileges, there’s no way I could have written this book.

INTERVIEWER

You wrote the whole book over two months of sabbatical. What was that writing process like?

ZACHARY LESSER

For the most part it was relatively smooth. There were moments of complexity and doubt, where I worried that it would fall apart, but they mostly happened earlier in the project, over the course of writing the talks. Much of the writing difficulty and the terror of the blank page had already happened. I always get anxious, every time I commit to giving a talk, that I simply won’t be able to write the thing and I’ll have to stand up there and confess that I have nothing to say. But since I’d been talking about this material for a few years, by the time I came to write the book I had become comfortable with the loose ends and frayed bits. And in fact those loose ends became part of the story that I wanted to tell.

If you think of bibliography as a science or a form of detection, there’s a risk that you feel every piece of evidence has to fit perfectly. We tell students when they write an essay: always let in the material that doesn’t fit because it makes your writing more interesting. But you can’t help but be sucked into that mode with bibliography. Luckily my recursive talks on this project shook me out of that mode, because things often didn’t fit! And I hope the book reflects that.

INTERVIEWER

In the early material on the Pavier Quartos at the start of the twentieth century, figures like Greg, Neidig, and Pollard sometimes wrote with a kind of priestly authority, presenting the solution or the explanation.

By contrast, I was struck by how your book remained open to uncertainty. The book ends with a series of questions, for example. That appreciation of ambiguity seems in some ways closer to literary critical work than to bibliography. Could you say anything about the role of uncertainty in the discipline at the moment?

ZACHARY LESSER

I think part of this is the coming together of bibliography and book history, with the different interests and theoretical underpinnings of those adjacent fields. However, I do think that when you go back and read the original essays of the New Bibliographers, they are generally more nuanced than you remember. Then later other people pick up on certain points and those points become ossified.

Part of what prompted my ending with a series of questions was that I had the experience at Trinity College of looking at Edward Capell’s collection of Pavier Quartos in two volumes. This is the set of quartos that W. W. Greg knew best, because he was the librarian at Trinity College. And I saw that this collection contained a ghost of Woman Killed. Now, W. W. Greg is the greatest bibliographer in our field, or one candidate anyway. He made no mention of this ghost and I don’t think he saw it. There are lots of reasons for that. I don’t know what kind of lighting conditions he had at the Wren Library, for instance. But it’s also true that if you’re not looking for this ghost mark, it’s invisible. And even if Greg had seen it, he would I’m sure have felt that it had very little to do with the original publication.

If I’m seeing something that W. W. Greg did not see on these copies, it’s not because I’m a better bibliographer. It’s because I’m working in a totally different context. And if that’s the case, nothing that I say will be iron clad for someone else ten or twenty years in the future. Almost literally, some kinds of evidence are visible at moments and others are not. Marginalia, for example, is a huge area of scholarship now but it’s not something that Greg and Bowers were interested in because it couldn’t tell them anything about the author’s text. So my interest in uncertainty stemmed from this central question: how can our arguments cope with this problem of what we can and cannot know?

INTERVIEWER

There’s a delicate balance here between making arguments but at the same time making the work self-aware about its own limitations.

ZACHARY LESSER

Yes. And that balance is a disciplinary moment. We had twenty or thirty years of real critique of the New Bibliographers, which was I think a necessary critique. Now it feels to me that we’re at a moment where there’s more acknowledgement of the incredible work they did. We need to take up their tools and use them for new ends.

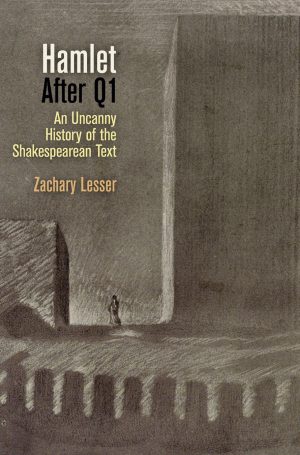

Part of my thinking comes out of the conclusion to my book on Hamlet because I think the same problems are at stake in editing. There was a lot of critique of the editing that came out of the New Bibliographic era and that critique gave us decades of unediting and versioning. What I argued in the conclusion to the Hamlet book is that unediting has gone as far as it can go. I think now we need a return to the belief that we can edit but also to combine that belief with fresh humility. We can’t just throw up our hands and say: all we can do is present the text as it appeared in its early edition. There were arguments in the nineties I remember that said: ‘we shouldn’t edit anything’, and ‘we should just use facsimiles’. And I think that just gives up on a whole area of scholarship–editing–that is an important form of literary criticism. It’s like saying that we shouldn’t write anything about King Lear anymore. So I think we need to find that middle ground that absorbs the critiques that emerged out of poststructuralist theory and carries those ideas forward into a new sense of what it means to be a bibliographer and an editor.

INTERVIEWER

A related question is: what does it mean to read, at any particular historical moment? Any mode of editing

Hamlet After Q1: An Uncanny History of the Shakespearean Text (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016)

involves assumptions about how much work you expect a reader to do. After all, you can hand out facsimiles of King Lear, but what are the burdens and duties that the act of reading those facsimiles involves? Our ideas about what it means to edit involve a set of assumptions about what it means to read.

ZACHARY LESSER

And if you push un-editing too far, you end up reifying one material instantiation of a text. And granting it a kind of authority that in practice it doesn’t have. Once you accept that the word ‘aud’ is probably a typo for ‘and’, you’ve kind of opened the door to altering other words you think are incorrect. At the same time, this form of tinkering becomes addictive to the editor.

And if you look at the history of editing and read editors back to the eighteenth century, the field is filled with megalomaniacs! Because it’s addictive to think you can divine the text of Shakespeare better than those who tried in the past. So we need to check our own scholarly hubris.

~

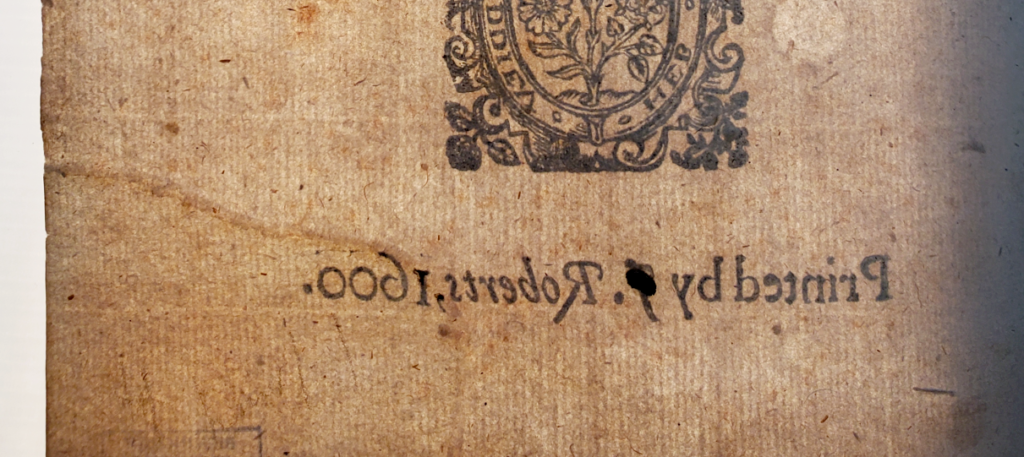

‘The kinds of bibliographic evidence that had not been used much, or even known about’: the reverse of a tear-and-repair imprint from the Library of Birmingham’s copy of Merchant of Venice (STC 22297, S336.16). Image credit: Zachary Lesser and the Library of Birmingham.

(2.) Early Career Life

INTERVIEWER

Could you talk about the process of getting your doctorate and the challenges of finishing your thesis and getting your first job at Illinois?

ZACHARY LESSER

I hesitate to even talk about those challenges when thinking of the early career scholars who will read this today. It’s just night and day, what academia was like when I finished graduate school in 2001 compared to how it is today. There were a lot of jobs that I applied to that year. A lot of research jobs. Now there’s maybe one or two each year. So, looking back on it, I feel like it was the last generation of academia where there was still a fairly good chance of getting a permanent job. It’s amazing how the field has shrunk in the last twenty years and that’s very dispiriting.

My graduate school experience was exciting. I moved to New York, I had a great cohort of students at Columbia, some of whom I’m still friends with today. And it was a nice moment in that programme. There was real esprit de corps. I think that becomes harder as jobs shrink.

Then I got this job in Illinois and moved to the mid-west, where I’d never lived. It was a culture shock. It’s the same country but the US has many countries within it. Illinois had hired a tonne of people–and keep in mind this was a public state university. When I came in there were seventeen assistant professors in the English department. I have no idea what the equivalent numbers at Illinois are now, but most English departments have shrunk considerably.

It was exciting, because there were other people starting with me. That’s helpful when you’re moving through the tenure process. You need people you can have a beer with who are also untenured. You can never have quite the same conversations with friends who will eventually be voting on your tenure. I feel lucky to have gone through that period in my career when I did.

INTERVIEWER

Your doctoral thesis later became your first book: Renaissance Drama and the Politics of Publication [Cambridge University Press, 2004]. How long did it take you to transform the thesis into the monograph?

ZACHARY LESSER

The book came out in my third or fourth year on the job.

INTERVIEWER

So you got your job before the book.

ZACHARY LESSER

Yes. That was a fairly common pattern back then. I got the job in February or March before finishing up my dissertation. After defending the dissertation in May or June I moved out to Illinois to start in late August. Again, it was a period in the American academy more broadly when there was more support for the humanities. So in my first three years I had two semesters off. One that they gave all junior faculty and one because we had a humanities centre on campus where you could have a semester free from teaching just to focus on your research. So I was able to get the dissertation revised into a book within the first couple of years that I was there.

INTERVIEWER

What did your revisions entail?

ZACHARY LESSER

I didn’t remove or add a chapter but I changed the organisation. I moved some things around and gave the material a different through-line; I added a different introduction and conclusion. But what helped me was that the dissertation already had the basic spine of the book. Which I credit to my graduate programme and my advisor David Scott Kastan. Columbia and David were both very good because they acknowledged the need for graduate students to become professionalised. Which I think a lot of Faculty resisted, out of good motives, because they didn’t want to increase the pressure on students and cave to the increasingly corporate culture of the university. But I felt well served by just the frank acknowledgement that you must think of your dissertation as further along in that process than you might be comfortable with.

The good thing for me was that I didn’t need to go and research an entirely new chapter, which is what takes the most amount of time. My work was mostly revisions that didn’t require me to burrow into a library for six months before coming back to the writing.

INTERVIEWER

You must have been delighted at the book’s reception. It enabled a great deal of work over the following ten or fifteen years and remains heavily cited.

ZACHARY LESSER

That book really began from a single idea: that we can think about publishers’ lists as a form of reading. That idea is really a method, not any particular content or argument. My hope was that other people would take up that method, and watching this happen was the most gratifying thing about the reception of the book. Of course it’s fun to write something and people think it’s great. But when other people take up the work and do something different with it, that’s when the work becomes diffused and takes on new life.

In the end, the individual arguments I make about particular plays in the chapters of that book are not why people like it. If you read criticism on The Roaring Girl, I don’t think my work is often cited. People don’t read my book because it tells them what The Jew of Malta meant in the 1630s. I think the positive reception was entirely because of the portability of the method of reading, and the way that it allowed for a new lens on old material.

–

‘My first book is surrounded by the army of scholarship that you need for the dissertation. That’s fine, but it’s not the kind of thing that I can bring myself to do now… I think it’s what everyone ends up doing for a first book.’

–

INTERVIEWER

When you look back now at that first book, in what ways do you feel your writing has changed?

ZACHARY LESSER

My writing has definitely changed! I never would have had the nerve or self-confidence to write this most recent book when I was younger. I haven’t looked at my first book in a long time and I don’t plan on it. I don’t think you should look back on anything you wrote after any significant amount of time has passed because it’s always just disappointment. But my first book is littered with tonnes of footnotes. It’s surrounded by the army of scholarship that you need for the dissertation. And that’s fine. But it’s not the kind of thing that I can bring myself to do now. And there’s a lot of material that could be trimmed from that first book without any loss. But that mode of writing is where I was, and I think it’s what everyone ends up doing for a first book.

So really the pleasure of writing this book on the Pavier Quartos was that I felt like more of a writer, partly because it wasn’t spread over years and endless redrafts and having a dissertation committee. It felt more like a writing project, whereas the first book felt more like a research project than a writing project. Obviously both sides are always present.

INTERVIEWER

The development in an academic career from writing defensively to a looser, more streamlined style, seems a common trajectory.

ZACHARY LESSER

Yes. I remember when I was trying to revise the dissertation into a book I asked mentors for advice. My mentors told me: cut the footnotes. They would say: you’re going to be more confident, more assured. But it’s hard to pin down what that means in practice. My first book is more assured than my dissertation. But not that much more! I think these shifts require time and experience.

I speak with graduate students about this regularly: it’s very hard to specify what that transition from a thesis to a book is like and how to do it. I wish I had a better answer because I don’t like giving mystical advice like: ‘you just have to feel your way to a more confident shape for the material’. But it’s hard to pin down pragmatically what that change should entail.

INTERVIEWER

What kinds of things do you say to those graduate students who ask for your advice?

ZACHARY LESSER

Well, there’s a lot of anxiety and fear at the dissertation stage. When you’re writing defensively or anxiously the sentences get worse. They get convoluted and impacted. I tell students to be aware of that.

One of the big changes in an academic career happens when you get a job and you’re working and teaching every day. I think letting some of that teaching style into your writing is useful; it makes the writing easier to read and more fluid and more narrative.

Having a job where you feel some stability is a huge part of it, too. Going from job to job, each one lasting about a year, is not conducive in any way to good writing. Quite apart from the demands on one’s time, you don’t have the same assurance that develops when you’re in a permanent job. This is the most depressing thing about our field.

INTERVIEWER

What are the next challenges for your field?

ZACHARY LESSER

I’m sure I’ll be wrong. In book history there’s a lot of interesting work at the moment that traces the long history of things. The books that we work on have gone through so much transformation over the centuries. When I was in graduate school, book history meant a way of doing New Historicism. That is, of getting back to 1603, say. Now there’s some really interesting transhistorical work going on. My colleague Whitney Trettien’s work is great at doing this. Parts of her work are in the sixteenth or seventeenth century; parts of it are in the nineteenth or twentieth. There’s less anxiety about something being anachronistic. She traces formal or structural aspects of books in different historical moments without worrying that this method opens her up to critique about her arguments.

INTERVIEWER

Peter Murphy and Jane Kingsley-Smith’s recent books do similar work.

ZACHARY LESSER

Right. After all, the books themselves in which we’re interested are not locked into any historical moment. They persist across time. That’s one of the interesting features about them that has traditionally received less attention.

~

‘The thing that you least want to write about in your chapter or book is probably the thing you most need to write about’ – Zachary Lesser

(3.) Writing Habits

INTERVIEWER

What might a good day of writing for you typically look like?

ZACHARY LESSER

The writing happens before my kid gets home from school on a day when I’m not teaching. I used to work a lot at night and I can no longer do that. Even before having a child, I stopped being able to work after dinner at some point.

INTERVIEWER

I’m already there.

ZACHARY LESSER

If I write for an hour or so, that’s really good. And I really like it when I’m on a roll with writing and I come to a stopping place that feels like a natural pause but isn’t the end of the roll that I’m on. That way I can pick up for the next day.

Typically I don’t get much writing done during semester because I need multiple days in a row, even though I don’t write for long on any given day. And if I’m teaching, even for just a few hours, I can’t do anything else that day. I need those days where there’s nothing to do but write. You know when you were a kid in the summer and it felt you like you had those days of endless nothingness ahead of you? That’s what I need for writing.

INTERVIEWER

Why is that?

ZACHARY LESSER

I need the brain calm. I need this elongation of time which I’ll never fill.

INTERVIEWER

Is the physical space in which you write important?

ZACHARY LESSER

Less so. On my sabbatical in Bologna we had a small flat. My partner is a poet and space is very important to her writing. She would start working and I would leave the apartment. I wrote my book in a whole variety of bars and coffee shops. Once I start writing I can lock in and write with people and music and hubbub around me. Where I am doesn’t matter all that much, though it was helpful that the coffee was always good in Italy.

INTERVIEWER

How helpful is academic Twitter?

ZACHARY LESSER

It can be useful and it can be terrible. I try to restrict myself to only tweeting about old books; then failing; then regretting that failure; then periodically deleting all my tweets that aren’t about old books.

I think there’s more book history on Twitter than there is early modern studies in general. And it’s very useful! Often you’re sitting with a book and see something you don’t understand. You can take a picture of an inscription or a difficult hand or owner’s mark and ten minutes later someone will have the answer.

I also feel like our little area of early modern studies is a good community and inherently collaborative. You get a range of perspectives and knowledge that I don’t have but a curator or book conservator might have. That’s been useful for me in researching the book. Although it was not at all useful in the actual writing–there’s always something else to read instead of doing your work.

INTERVIEWER

What are the major challenges or problems for you in your writing practice?

ZACHARY LESSER

Finding time, of course. There was a whole chapter of the Hamlet book that I wrote with my infant son in one of those sling pouches, napping on my chest. The first six months or year of having a child involve great sleep deprivation. I became extremely focused and could work for an hour while my son was napping in a way that I’ve never been able to do before or since.

More broadly, I always worry that a chapter just won’t work. I worry I’m building a house of cards that could just collapse. So, for example, if I have this idea about the ‘to be or not to be’ speech in the context of Q1 Hamlet, my fear is that I write the whole thing out, and then come across one newspaper article from the 1860s that makes it all fall apart. This never in fact happens, but that fear can create writer’s block. The fantasy is that you’re creating an argument that is so well constructed that it becomes this impregnable fortress. But then no-one can get in. And no-one cares.

–

‘The fantasy when writing that you’re creating an argument that is so well constructed that it becomes this impregnable fortress. But then no-one can get in. And no-one cares.’

–

INTERVIEWER

What helps you manage this particular writerly problem?

ZACHARY LESSER

I remind myself that writing about literature isn’t a feat of engineering. When writing my dissertation I had some advice from Julie Crawford, who had just started her job in Columbia. In a dissertation workshop, someone asked me: what about this? I can’t remember what their issue was, but anyway, I mounted this ten-minute response of why it wasn’t something I needed to deal with. And Julie told me: the thing that you least want to write about in your chapter or book is probably the thing you most need to write about.

I found her advice very helpful. Your problem is not the thing that’s truly irrelevant; it’s the thing for which you create an elaborate defence. For me, every time there’s something like that. And I waste a month trying not to do it. And then I finally do it.

–

‘The thing that you least want to write about in your chapter or book is probably the thing you most need to write about. Your problem is not the thing that’s truly irrelevant; it’s the thing for which you create an elaborate defence.’

–

INTERVIEWER

What was this thing for your most recent book?

ZACHARY LESSER

In this book, the first ‘rips and scrapes’ that I found were all on copies of the plays that were accurately dated 1619. And that fit in very well with the idea that someone was trying to hide that date, as with the falsified imprints, and perhaps they continued to try to hide it even after printing. But then I found several examples of exactly the same thing on plays that already had false dates in the imprint. And this threw me for a long time. I tried to think of ways, essentially, of explaining away this apparent contradiction. And what I needed to do was to write about this impasse and write about the bizarre fact that someone apparently re-falsified an already false imprint, rather than trying to get around it.

INTERVIEWER

What academic writing are you enjoying at the moment?

ZACHARY LESSER

I just got Margreta de Grazia’s new book, Four Shakespearean Period Pieces [Chicago, 2021], which I’m looking forward to reading. I love Margreta’s work—each book is a beautiful and crystalline piece that she’s honed for a long period of time.

I liked Jason Scott Warren’s book, Shakespeare’s First Reader [Penn, 2019] a lot. I like the way he tells that story. I read it as I was copy-editing my book and felt some connection with the way that he starts from this one journal entry and then moves into all these different areas, but you never feel lost. That’s a lovely divergent and meditative way of writing.

And then I just read in manuscript Jason and Claire Bourne’s piece on the Milton Shakespeare Folio. I love that kind of writing where there’s this real depth charge. They’ve gone so deep into this one book. I like this work lately that’s gone very deep on single moments or single books. I also love Adam Smyth’s writing. I think there’s a group of book historians doing work that’s a bit more playful and less hidebound by typical scholarly conventions. So in his recent book he engages in some fairly wild speculations about waste paper that in an older model of what is rigorous you probably couldn’t do. But he’s very up front about wanting to break down that kind of model.

INTERVIEWER

You’ve written several collaborative pieces, with Peter Stallybrass and Alan Farmer among others. What are the advantages of collaborative writing?

ZACHARY LESSER

If you find the right people it can be way more fun to write collaboratively. I imagine that with the wrong people it’s harder and worse, of course. But I’ve gotten lucky and I really enjoyed writing with Peter and Alan. Claire Bourne has an edited collection out [Shakespeare / Text (Arden, 2021)] for which I co-wrote a piece with Whitney Trettien, which was exciting to do. You learn lots of new things from co-writers.

Both my Hamlet book and the Pavier Quartos book emerged out of co-teaching some courses with Peter Stallybrass and then co-writing a short essay. We wrote a piece together on Q1 Hamlet and commonplacing [£], after which I kept thinking about Q1 Hamlet. And then we wrote a piece about the Pavier Quartos [£] and I kept thinking about the Pavier Quartos. I didn’t realise that till afterwards but both of those books wouldn’t have happened had I not ended up in a department with Peter.

INTERVIEWER

Is there anything you have discovered that works particularly well for collaborative writing, in terms of dividing up the labour or managing the practicalities?

ZACHARY LESSER

I think many ways can work so long as you are clear on who is doing what. When Alan and I first started collaborating, we were still in grad school, and we wrote in the same room, with one of us typing and the other sitting alongside, sort of writing aloud. That only works if you are physically in the same place, and I’m not sure it is the most efficient method, but it did mean that each sentence of those essays was thoroughly co-written. With Peter, we would meet once a week to prepare class, then we would have dinner and discuss the essay, then we would divide up sections to write, and then we would edit each other’s section. This was a bit intimidating to me, editing Peter Stallybrass, but he’s so generous and without ego that it produced better writing for both of us, I think. Writing recently with Whitney was a lifesaver at the beginning of the pandemic; it was a huge help mentally to have something fascinating to talk about and write about with her, instead of just doomscrolling all day. I think the crucial thing about collaborating is that you have to genuinely like and respect each other, or else it becomes so hard to be edited by the other person, to have your ideas challenged or rejected, and so on. But if it works, the sum is much greater than the parts.

~

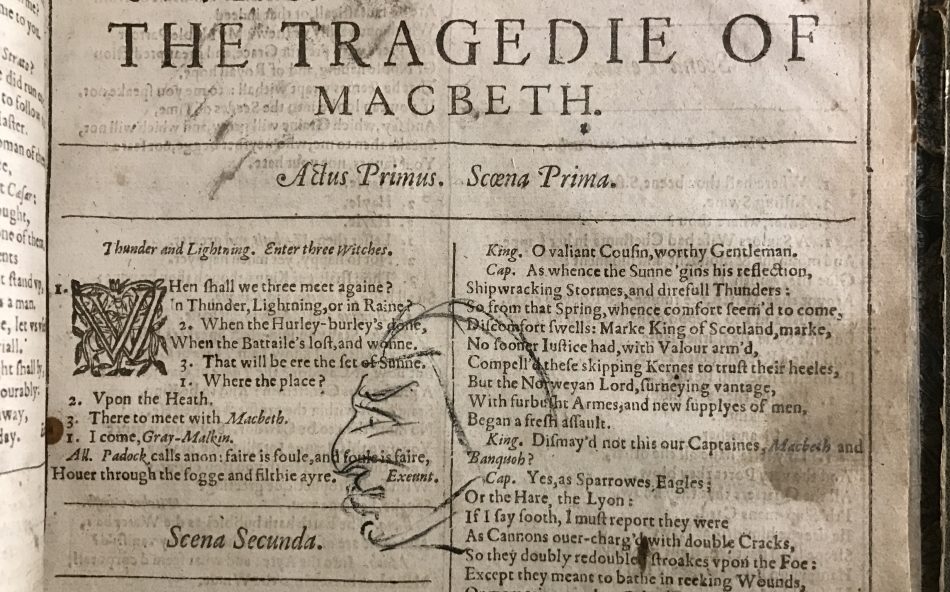

The opening page of Macbeth in the First Folio (sig. 2I6r). The play is being edited by Zack for Arden 4. Image credit: Folger # 168365 of Folger STC 22273 Fo.1 no.48.

(4.) Editing

INTERVIEWER

With Tiffany Stern and Peter Holland, you are one of the general editors of Arden Four. Where is that series at?

ZACHARY LESSER

We’ve commissioned a bunch of volumes but not all of them. This is the fun intellectual moment, where we figure out the editorial guidelines and find the right people for each of the plays and the poems.

One of the first things we decided was not to have a blanket editorial rationale, in the sense that, say, the Oxford Shakespeare focused on the earliest performance. Instead we ask each editor to have an editorial goal. They can’t simply say: ‘I’m going to reproduce the F text or the Q text.’ They have to have a goal that isn’t simply present in the early editions. The only restriction is that it must be an early modern text, meaning that an edition couldn’t be based on a nineteenth century revival, say. We’re trying to strike that balance between a more traditional editorial approach as embodied by Arden Two, and the versioning approach of something like the Arden Three Hamlet. It’s exciting to see what some of the volume editors are thinking about.

INTERVIEWER

You’re editing Macbeth for Arden Four. What’s your particular goal for that play?

ZACHARY LESSER

I’m still figuring this out, but for Macbeth, I think at least some of the Folio text is post-1616, post-Shakespeare–the songs, for example. So I think I’m going to reconstruct the text of some revival of Macbeth that incorporates all this material. This may have ramifications for the text at certain moments, since the play may have changed between when Shakespeare wrote it and when the revival that underlies F was performed.

INTERVIEWER

Can you say anything about what it means that Arden Four will be a ‘digital first’ edition?

ZACHARY LESSER

Right now we’re still figuring out what that means. We’re still going to print some, but the idea is that these editions are created digitally first and then you can offshoot them into print or digital. That should allow us to do some interesting things with sound and imagery, for instance, as part of the commentary.

~