Paper kingdoms 5: emma smith

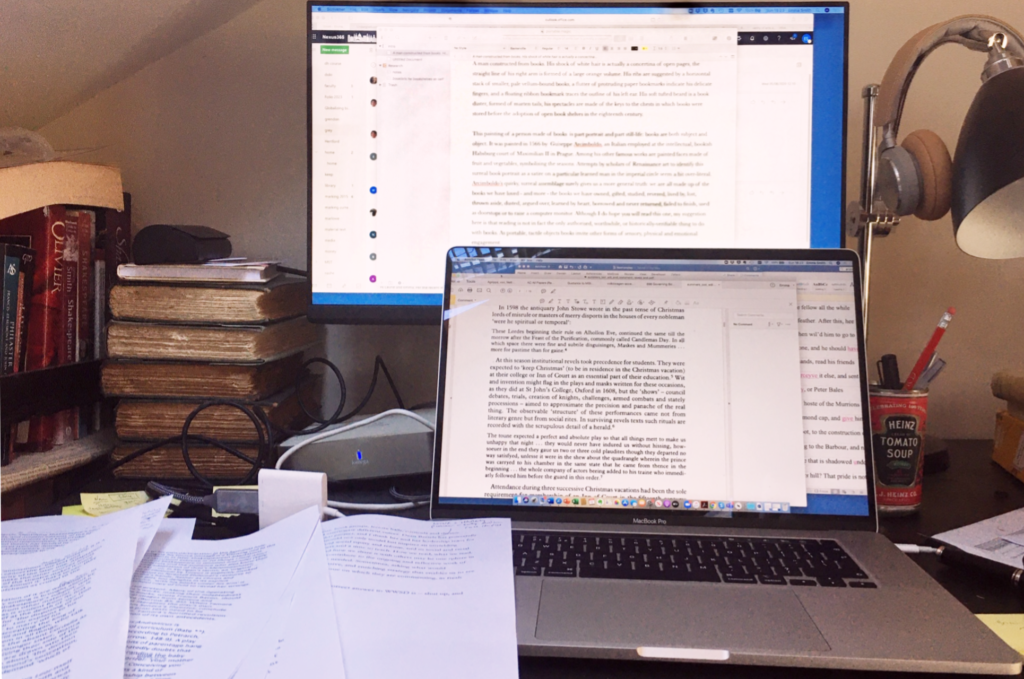

‘Scrivener tells you how near to your target you are. Happily it doesn’t know whether the words you’ve written are any good’: Emma Smith’s writing desk

Emma Smith is Professor of Shakespeare Studies and Tutorial Fellow at Hertford College in the University of Oxford. Before that she was at Somerville and All Souls Colleges, Oxford, and at New Hall (now Murray Edwards College) in Cambridge. Emma is a central member of the early modern community in the English Faculty at Oxford, but is known internationally as an authority on Shakespeare, early modern drama, theatre history, and ideas about collaborative authorship. Over the last ten years or so she has worked steadily on a variety of projects, many of which have focussed on Shakespeare’s First Folio. She led the project to digitise the Bodleian Library’s copy of the Folio, wrote a compelling cultural biography of the book for Oxford UP, edited a Cambridge Companion volume, and has also written a deft and fascinating overview of how the Folio was made which tackles the terrifying task of synthesising oceans of relevant scholarship with brilliant style and wit. Her most recent book, This is Shakespeare (Pelican, 2019), has been universally praised for its dazzling close-readings and steady commitment to making the plays accessible without compromising their nuance or sophistication.

I first met Emma as a student on the early modern M.St course at Oxford, where I took her course on Shakespeare. I remember being given the task of digging out interesting things to say about the Droeshout portrait that appeared on the front of Folio editions through the seventeenth century. I was struck then as I still often am by her unusual balance of both research brilliance and pedagogic flair (Emma’s iTunes lecture series on Approaching Shakespeare is a great starting point to get a sense of her abilities in both these areas). Having recently finished writing my own book on the First Folio, I found myself turning to her work all the time to check things or dwell in her prose style. I would set her alongside academic writers like Jason Scott-Warren or Adam Smyth for their shared commitment to trading dry academic register for writing that is in tune with the life of their ideas, and that can be read for pleasure on its own terms.

We spoke via Skype during the summer quarantine period for around an hour and a half. The conversation is organised into: (1.) Writing, in which we talk about how to shrug off a weighty revise and resubmit edict, the importance of curating your career profile, and writing collaboratively. We spoke briefly in (2.) Doctoral Thesis & its Afterlife, and then (3.) Research involves some queries about research praxis but also blurs back into writerly habits–why Emma prints her writing out to read; the difficulty of beginnings, and so on. Many thanks to Emma for making time to talk and for supplying the image of her workspace above.

(1.) Writing

INTERVIEWER

What does a good writing day look like for you? Do you have any particular habits that foster a sense of productivity?

EMMA SMITH

A lot of my writing I feel I do squeezed in between other things. I used to think that was a constraint but I now think it’s an opportunity.

At a certain stage of my research I write well in two-hour blocks, or in hour and forty-five minute blocks. That’s a good length for me. An empty day is not all that productive because I waste time and fiddle about. So quite often if I’m in between things I’ll use a timer, and tell myself that I’m going to get as much done as I can in this amount of time. I find that helpful.

I’m not particularly precious about the environment that I need. I don’t need to have all my notebooks ordered in the right way or anything like that. I’m a bit haphazard and contingent as a writer and sometimes I feel my writing suffers because of that. I often write lots of quite short bits.

INTERVIEWER

Why do you feel your writing sometimes suffers because of these habits?

EMMA SMITH

Well, I sometimes look at my work and think ‘this is lots of sections’. And the sections are all fine, but whether there’s a sufficiently strong through-line joining them all — I’m not always sure. I use Scrivener, particularly in the first half or two-thirds of any project. And Scrivener is fantastic for collecting little bits of stuff, scraps of thinking. Either my writing practices create that problem of being lots of sections, or perhaps they respond to it. I’m not sure which.

INTERVIEWER

You write in various different modes: you publish mainstream academic work, crossover more mass-market work, and often write journalism too. Are you conscious of approaching those writing styles in different ways?

EMMA SMITH

I do think they’re different registers and they need to be. Writing crossover work that seeks to communicate to non-specialist audiences has, I think, had an influence on my more academic writing. I like the idea that you can code-switch a bit in academic writing, meaning you can bring in something that’s more idiomatic or seemingly a bit more casual than some of the very mannered academic prose that we’ve all imbibed through graduate school and our reading.

INTERVIEWER

When did that practice of code-switching in your writing start? It seems an important feature of your prose style and gives your writing a wonderful clarity and freshness.

EMMA SMITH

I think I’ve become more conscious of that habit over my career. This is Shakespeare [2019] was published by Penguin. Writing that book wasn’t completely different for me but it was an extreme example of things I’d thought about before, in terms of what might be an appropriate tone to strike. I knew the tone had to be informed a bit by teaching but mustn’t be too teacher-ish, because that has its own issues. Sometimes teacher-tone is more authoritative. It may seem more casual and relaxed but is really conscious of a power imbalance: you’re in charge and the readers have to suck it up.

But I’ve never had a long period of research leave. I’ve never had a research fellowship, and I’ve never particularly wanted to have one, because I’ve always felt that writing falls somewhere in between teaching and talking about things. It’s not so much of a separate sphere from those other communicative forms. So I think I’ve probably always felt as though writing was on a continuum with teaching and discussing, rather than occupying its own separate sphere, and that influences my style.

INTERVIEWER

Did securing a permanent job bring about any changes in your research attitudes or writing practices?

EMMA SMITH

Almost certainly – but – and this is a real sign of the times, I know – I was so fortunate to get a job before I had gone through the years and years of precarity that has now been mainstreamed as part of an academic career. So I was lucky, and threw myself into teaching, and probably took my eye off writing for a time.

INTERVIEWER

Do you enjoy writing? What are the main emotions you associate with the process?

EMMA SMITH

Yes, I enjoy it very much. I enjoy language and vocabulary and one of the things I’m often most conscious of when I hear other people giving academic papers or I’m reading journal articles is I’m often really conscious of the critical vocabulary people use. I’m quite a magpie, I’m often struck by a phrase or a word and will think, what a fabulous thing to say, or a really interesting new word.

I do enjoy writing and I don’t tend to find it agonising. Although like everyone else I have times when I’m writing words but they’re not really all that helpful to the larger project.

INTERVIEWER

Is there a piece of writing of which you feel particularly proud?

EMMA SMITH

It’s interesting how difficult a question that is. It’s tough to think back to things and find something that I’m particularly proud of.

One thing that was an interesting writing experience for me concerned an article from about ten years ago called ‘Was Shylock Jewish’ which was published in Shakespeare Quarterly. That was an interesting experience, because, as probably most people who have submitted to SQ or to a journal like that will know, you get really substantial ‘revise and resubmit’ instructions. I don’t mean just ‘take account of this’ or ‘explain this thing a bit more’, but in fact two really long, detailed, quite divergent reports. Those reports were useful and constructive but in some ways overwhelming pieces of feedback. So that was an interesting experience for me, and it’s one of the reasons that I think writing for journals is really important, because that’s still the time when you get most detailed feedback and work hardest to revise something. A book you might get feedback on overall, either on a proposal or on some chapters, but probably nobody goes through it in quite that level of cruel detail, to tell you that this piece of work should be completely re-thought around this one question which is currently at the margins of it.

But that article and that feedback was a positive experience for me, because although the re-writing felt overwhelming and in some ways felt like something I really didn’t want to do, the result was much better for it. Much better.

That experience is in my mind because I’ve got another very extensive revise and resubmit that’s just come in. And I keep thinking: ‘this is going to be fine. This will be better’. Even though it’s a bit too much at the time. I’ve obviously published things before and have had revise and resubmit guidance in the intervening years between that Shakespeare Quarterly article and now, but never in such a substantial way that takes issue with both the structure and the argument.

INTERVIEWER

Could you talk a little about how you responded to that horrible-but-helpful revise and resubmit feedback on your Shylock? How long did it take you to rewrite the piece?

EMMA SMITH

I think I probably did what everybody does, which is to look at them first and think, ‘Oh God. Everything I’ve done is rubbish’. And then to come back to the reports after a week or two and start to organise the points: small things and big things. Overall it probably took me another six months till I submitted it, but of that time I probably spent a couple of weeks on the actual work of revision. But I think everyone overreacts to readers’ reports or criticism when it arrives, and feels either angry and misunderstood or overwhelmed. I’m no different.

INTERVIEWER

How conscious of your writerly style are you, in terms of using literary techniques like imagery?

EMMA SMITH

I’m quite conscious of it. I’ve been doing some op-ed type writing about Shakespeare and plague and I had a working list of COVID vocabulary to see if I could draw on it to develop the analogies.

INTERVIEWER

If you could give some advice to yourself when starting out as an academic writer, based on what you now know works well for you, what would you say?

EMMA SMITH

I’d say: spend a longer time reading and thinking. Even if just for a few hours a week in the lead up to writing, say, an article. And then try to spend concentrated time bringing it together. Then there’s another, shorter stage of reading, or sometimes backfilling, having realised that I need to understand more about this field, or this author or text. And then a final stage of drafting. And I’d also say, try to write like you speak, or like your best speech.

INTERVIEWER

How do you feel your writing has developed over your career?

EMMA SMITH

I think like everybody I’m more confident. Not an enormous amount of my writing is really detailed; I don’t think that’s a strength of my work. So I think my writing has had to find other ways of being persuasive across a larger sweep. And that’s the thing you can never do in a doctoral thesis, for example, because you’re always trying to check every box. It’s a very defensive edifice in some ways, stockaded around. I think I’ve been able to get beyond that in my writing since then.

INTERVIEWER

Can you think of a recent problem you’ve encountered in your writing?

EMMA SMITH

Something comes to mind which happened towards the end of my OUP book [Shakespeare’s First Folio: Four Centuries of an Iconic Book], the book I had wanted to be called A Biography of the First Folio.

INTERVIEWER

Why didn’t you call it that?

EMMA SMITH

Well, the publisher was very keen that if it was to be any kind of a crossover book, it needed a more descriptive title. But the introduction to that book still has an identity as a biography in mind — that introduction is all about object biography, or biblio-biography. I sometimes think I should have held out in doing that. I wonder if I’d feel differently now having had a book with a trade publisher, where there’s a bit more back-and-forth about what it should be called.

The New Oxford Shakespeare wasn’t going to come out till the end of the anniversary year, and I think OUP wanted some Shakespeare stuff to push out in 2016. My book was a great beneficiary of that. It was not originally intended to have that kind of profile.

INTERVIEWER

You mentioned a problem you encountered towards the end of that book.

EMMA SMITH

Yes. By the end of writing it I had come to see that I was saying the First Folio is this extraordinary McGuffin or Maltese Falcon of a thing. You have to wonder, why does everyone want this? And so my book became a history of a fetish and of an extraordinarily over-valued object. And I had started to worry that my book was enacting its own premise. It was trying to make an account of this phenomenon, but was also participating in the phenomenon itself in a way that was impossible to reconcile.

I felt these things powerfully at the end of the book. My aim had been to start the book with the first person we know had bought a Folio, Sir Edward Dering. And Dering is all about clothes and purchases and self-fashioning. And then I was going to finish with this eccentric guy named Raymond Scott, who was on trial for handling stolen goods: a First Folio that had been stolen from Durham University. He had turned up at court wearing Versace jackets and in an open topped cream Rolls Royce. He was an eccentric and over the top figure.

But just as I was writing that last bit I discovered that this man had killed himself in prison. He’d got a very long sentence; in some ways a ridiculously long sentence for a non-violent crime. I love books as much as anybody but I don’t think that tearing a page of a book, however venerable that book is, makes you a danger to the rest of the world. He had got a very long sentence and killed himself in prison. And suddenly that was a real ethical problem for that book. I felt that the overvaluation of the First Folio that I had worried about suddenly took an enormous price. And I felt that bibliography and book history stuff had contributed in a way to this situation. I thought it was very striking that the leading bibliography expert on the Folio was the expert witness at the trial, and it seemed as though bibliography had taken on this very dark aspect.

So that was a big process for me. I had just about finished the book. It was a book I had been working on for a long time and it was a serious research-driven book that I felt I needed because I felt I was becoming entirely associated with more pedagogical books. So in all kinds of ways it was doing a lot of work for me. And then I just felt, ‘Oh God, it’s turning to ashes’. I don’t think I really resolved that, although I did publish the book. And I tried to set out that dilemma at the end of it.

INTERVIEWER

You mention being conscious of becoming associated with more pedagogical books. How important is it to curate your research profile in that way, do you think?

EMMA SMITH

It’s been important for me not to get pigeon-holed. In some ways it’s been a disadvantage in my career that I’m not the go-to theatre history person, or the go-to performance person, or the go-to whatever, but that I do all sorts of different kinds of work. But I enjoy it and it keeps my research conversations broad and productive.

A very eminent public Shakespearean advised me that they felt their academic credibility had been fatally injured by writing trade books – and that’s stuck in my mind. I have wanted to try to keep a proper, peer-reviewed, new-research part of my work really active and alive as the source of, even the permission for, other kinds of communication. I think variety is probably important in everyone’s career – there are different learning experiences and affordances from, for example, an edited collection or journal special issue, or a collaboration, or an exhibit, alongside academic articles and books.

INTERVIEWER

Do you feel that Shakespeare’s First Folio: Four Centuries of an Iconic Book achieved what you wanted it to do in terms of complementing your profile?

EMMA SMITH

Yes and no. In a way I wanted to write a book that was going to cost £65. That had become the shorthand for a particular kind of academic credibility. So I was delighted to get the chance for a more crossover book and also thought that the chance to write a really properly arcane book had been snatched from me at the last minute.

INTERVIEWER

You also write collaboratively. Can you talk a bit about that?

EMMA SMITH

I love writing collaboratively. It’s enormous fun.

There’s quite an element of talking, particularly with Laurie Maguire, with whom I’ve collaborated a lot. We meet and discuss things we’ve read; sometimes we read the same thing and then talk about it — things we liked, things we disagree with. Sometimes we divide up a writing task into different sections, saying something like: ‘you pursue that line, and I’ll take a look at this aspect’. Sometimes we do the same things and see where we both get with it.

It’s good to collaborate with someone who works harder than you do, which is certainly the case for me with Laurie, who works a lot harder than I do and so keeps me at it. But it’s also great that the project is continually developing even if you aren’t in front of a document yourself. For me it’s been intellectually and practically very positive. It’s made me write things I wouldn’t otherwise have written and explore things I wouldn’t have explored, and take advantage of someone else’s talents. I would say my experience of collaboration with Laurie, with Tamara Atkin who I wrote an article with, with Andy Kesson who I wrote and edited with — in every case it’s been really positive and I think we should do more of it.

INTERVIEWER

I can imagine it changes a lot of the more agonistic aspects of writing. The ‘me in my garret’ stuff.

EMMA SMITH

Yes. And I think it helps you to be a bit less precious about your own prose. There are compromises in that but that seems well worth it in the scheme of things.

(2.) Doctoral Thesis & its Afterlife

INTERVIEWER

Your doctoral thesis was on foreign immigrants in early modern London, and specifically on their representation in drama. What was your doctoral experience like?

EMMA SMITH

I remember my doctoral work as quite an isolating experience. I had quite a difficult supervisor and I think I was writing at a time when graduate culture, as a cohort, seemed much less developed and participatory than it is now. So I remember my thesis as an isolated time in my life. And I didn’t feel I had any real advice about what to do with it once I was finished.

By the time I finished I had picked up a couple of other projects. And of course, when you’ve finished your thesis, you’re often not that interested in it, and feel as if you’ve had enough of it. So it was very tempting to move on to other things. John Pitcher asked me to edit The Spanish Tragedy for a new Penguin old spelling set of texts, which was a short-lived but rather wonderful editorial project. That project helped me to meet a lot of much more senior colleagues and taught me a lot about editing and drama and academic culture. So I moved into those circles. And then I also had a contract based on a paper I’d given to do a stage history for Cambridge of Henry V, and I wanted to develop my theatre history credentials, so I got on with that. I moved into those other things with great alacrity and relief and didn’t ever go back. I don’t think I’d recommend it as a course, but that’s how it worked out for me.

INTERVIEWER

Did you consider publishing your thesis as a book?

EMMA SMITH

No. I never published my thesis as a book. Which was just about still a possibility at the end of the nineties, and isn’t really a possibility now. I published three chapters from it, and then in some ways in that Shylock piece we’ve been talking about I wrote a more measured and distanced summary of the things that I had been interested in before but hadn’t known how to put together. So I published quite a lot from it but didn’t develop it into a book.

INTERVIEWER

It sounds as though your thesis did have an afterlife, but not an immediate one, and not as a monograph. You fragmented it into three articles and then later a fourth.

EMMA SMITH

Yes. My thesis was probably the most historical piece of early modern work that I’ve done. And I suppose that kind of historicism still seemed the thing that you did with early modern drama in the nineties. But I think the connections between the historical contexts I’d unearthed and the literary texts were not sophisticated enough. It was kind of clear to me at the time and is certainly clear to me now. I was tussling with a late-stage historicism, where other scholars were asking ‘well, what is the relationship between these two things?’ And I don’t think I answered that to my satisfaction. But now I’m less in hock to historicism as a mode it’s more possible to go back to some of the material and ask what it was for.

(3.) Research

INTERVIEWER

Could you talk us through your process for a new research project?

EMMA SMITH

I haven’t really got firm habits. Most of what I do is digital, just for the convenience. For each new project I’ll start a new Evernote folder, sometimes multiple folders. So I use Evernote to make on-the-go jottings, which I do on my phone. I’ll also take photographs on my phone and download PDFs onto my phone, all of which I’ll keep in Evernote. If I’m doing a piece of writing that’s more than about 1,500 words then I’ll probably do it in Scrivener first. I think Scrivener is a really powerful programme. I use it for the corkboard feature, which lets you compile bits and pieces of notes or a sense that there will be at some point a paragraph about this or that. And one of the things I like about Scrivener is that it will add up all that you’ve done in all the notes and tell you you’ve met your target for the day. I always set targets for how much I want to write.

INTERVIEWER

For the writing day, or for a project overall?

EMMA SMITH

Overall for a project, but also for the day. And then Scrivener will tell you how near you are for your target. Happily it doesn’t know whether the words you’ve written are any good or not.

I think I work quite a lot by numbers. It helps me to scope out whether the idea I want to cover is too much. I have a tendency slightly to write in a two-halves kind of way, so that you could split a lot of what I write in the middle. And the first half would be about some aspect and the second would take on another. And sometimes I don’t think the hinge is all that strong. Sometimes keeping track of the word count helps me to see that I really can’t do both of them, and I really only need to do the first part, or perhaps only the second part.

So if I had an article of 13,000 words, I would be quite tempted to say, ‘I think this is mostly about this phenomenon. And I’m going to need 5,000 words for that, and 8,000 words for that, or whatever. And I need this section to cover the background, and this to set up this term, and this as a coda. That helps me to see whether or not something is a feasible article.

INTERVIEWER

It sounds like you think quite clearly about the conceptual structure of a piece of writing, where you have a sense of how the overall word count of a piece should distributed within the arguments you want to make, rather than thinking through the writing, so to speak.

EMMA SMITH

I think the writing process itself does produce the ideas. I think what Scrivener shows me — and this is the flipside of all that word counting — is that there’s a huge amount of stuff that gets written and that doesn’t then end up as part of the finished piece. It’s not waste, as such, but there’s a huge amount of stuff that gets written as part of the process of coming to a sense of what needs to be done. All that materials is a kind of scaffolding that gets you to a place, and then you realise: I’ve spent 2,000 words explaining this but really I could have spent 100, and here I am.

Sometimes I find it hard to know with a piece of work that I’ve finished what the actual starting point should be. I think that’s an interesting question about academic writing. What do you do at the beginning? Do you do the anecdote which was so compelling to lots of us as a model of academic writing? Do you start within the text and make the text itself ask the question that you’ve made it ask? Or do you start by establishing the intellectual conversation in which these issues emerge? I find that a continually difficult part of the writing process. Often if I’ve got that, the rest of it is less difficult.

One good thing about keeping the work in sections on Scrivener for me is that I am able to edit and work on the text in sections. Whereas if I have a long continuous document, I keep rewriting the beginning. I just write pages one to six over and over again. And then pages seven to twenty, I’ve hardly looked at since I wrote them. Because somehow I always get tied up with the beginning whenever I’m editing and reworking. Scrivener helps me so that it’s not the case that every time I go back to writing I have to go back to the beginning.

INTERVIEWER

So Scrivener encourages a helpfully disaggregated form of writing. Whereas Word mimics a codex, with a beginning, middle, and end.

EMMA SMITH

Yes. I know in theory you can in Word have two parts of a document open at the same time. But I don’t know how to do that.

INTERVIEWER

You mentioned finding beginnings tricky. When do you write the beginning? Do you tend to write from start to finish, roughly, or does your disaggregated approach mean that you dart around within a project according to interest?

EMMA SMITH

I tend to need to get the beginning right-ish in order to shape the sense of the whole. So I do write some version of that first. But then the other bits sometimes take shape as independent paragraphs or ideas.

INTERVIEWER

You mentioned that you use Scrivener for the first two-thirds of a project, but then change?

EMMA SMITH

Well, for the last bit I’ll put the article together and I will tend to export it into Word to do referencing and formatting. I’ll never print out from Scrivener but I do from Word as part of my revising and polishing process.

INTERVIEWER

How does printing the material out help your writing process?

EMMA SMITH

It’s partly that it slows me down in reading. I can glance and glaze a bit when looking at my own work on a screen. So I’ll mark up a printed draft as a penultimate stage. And sometimes, depending on what it is, I might read the piece of work out loud. But not always.

INTERVIEWER

Do you edit and redraft much?

EMMA SMITH

Probably not as much as I should. I get to a point where I think: I could keep editing this but the gains are quite small. At that stage, I tend to be making it different but not necessarily better. And usually, like everybody, most of the academic writing I do has a deadline. All our writing has dual pressures, and one of them is the fact that you’re not writing till it’s finished, you’re writing till it has to be turned in. That’s not a bad thing.

INTERVIEWER

It saves us from falling into a Borgesian project of producing one work to endless perfection.

EMMA SMITH

Especially pages one to six.

INTERVIEWER

The last five years have been particularly productive for you. Can you talk about moving between projects? Have you ever struggled for ideas or for the next project?

EMMA SMITH

I’ve spent a lot of time working on the First Folio [for example, the Bodleian digital facsimile project and the Cambridge Companion, in addition to Emma’s individual books] and I still don’t think I’ve quite decided what the next big thing is that I’m going to spend ten years doing. I’ve got a long list of stuff I’d like to do: conference papers that I’ve never put together, or things I think would make a great article. So I sometimes do go back to that list in between times.

In some ways the biggest change to my working habits having written a trade book [This is Shakespeare] has been this: if you write a trade book, there’s a huge amount of work to do when it comes out. Whereas for an academic book, you’ve finished all the work long ago by the time it actually emerges. Nobody would expect you to talk about that academic work again, and they’d be annoyed if they asked you to come and speak, and you spoke about material that you’d just published. They’d be furious!

So, in a purely academic circuit you’ve got the gap between submission and publication. And by the time something is published you probably are at the stage of thinking about or working on the next thing. Whereas the process of marketing This is Shakespeare has been quite different from that. I’ve had a lot to do, and because live events aren’t happening during quarantine a lot of that promotional work has translated into writing of various kinds: writing blogs or opinion pieces for newspapers.

But every time I finish a project I think: that’s enough Shakespeare. I’m not doing any more; I’m fed up with it now. And I have usually then taken on a non-Shakespeare opportunity of some sort. That’s when I did bits and pieces of work on Middleton, and it was in a similar gap that I decided I’d take on editing Thomas Nashe. So that’s one of my ways of dealing with that in-between phase — to take on something completely different.

INTERVIEWER

Are you finished with the First Folio, with the four hundredth anniversary of its publication looming in 2023?

EMMA SMITH

I think so. But who knows. One interesting way to think about projects is whether you want to go back to them or not. Part of me would like to do a new edition of the Folio book for 2023. Not a facsimile, but just to update and reframe the book. I’d like to talk about the Folio copy that was recently found on the Isle of Bute and some of the stuff that’s come up since. And there are things that niggle me about my OUP book, and about my other Folio projects, which mean that I’d like to write them again or do them better. It’s hard to imagine that 2023 will be another bonanza Shakespeare anniversary but then, I said that about 2016, and that certainly was. Perhaps there will be a First Folio movie.

INTERVIEWER

What does your academic community mean to you, and how does that play into your research process?

EMMA SMITH

Community has become increasingly important to me as my career has progressed. I had a sense of my academic community much less at the beginning, partly because I’m not confident to ask people to do things and I didn’t feel as though I was within a reciprocal network with people for whom I would do the same kind of job. But increasingly I do now. So I have lots of people that I would ask to look at something or to help me think through something that was difficult or ask for advice about an area that I don’t really know about. So I think community in that way is really important.

INTERVIEWER

Do you find conferences a helpful part of your research process?

EMMA SMITH

I find big conferences a bit overwhelming and a bit performative in ways that don’t always feel very comfortable. I think the best conferences I’ve been to have been quite small-scale and focused — the kind of forum where everybody goes to everything. I went to a great conference on Nashe that was like that: it was hard work, but there was a strong sense of an ongoing conversation.

I tend to find the larger conferences, where there are many parallel sessions, a bit less useful. And I’m wondering now after this time of lockdown whether it will seem as feasible to get on a plane and go to the US to give a paper. Why would we, really? We’ve proved we don’t have to and there are all kinds of other reasons we shouldn’t. It will be interesting to see what that landscape looks like.

INTERVIEWER

That question will be particularly relevant for early career people. One of the functions of the conference has to do with the job market, doesn’t it, and showcasing yourself. I wonder how that will change.

INTERVIEWER

What have you read recently in early modern studies that you’ve enjoyed?

EMMA SMITH

I’m just reading Lucy Munro’s book, Shakespeare in the Theatre: The King’s Men [Bloomsbury, 2020]. This is a really brilliant book about the King’s Men repertory in the 1610s and 20s. It looks a lot at revivals and what the documentary evidence is for that and asks how plays like Pericles keep moving through the repertory. It’s a really smart book about theatre history and also about the conjectures one could build on archival stuff.

And I’ve just done a swoop through a whole lot of Arden 3 material about editing in order to review the last of those volumes: Measure for Measure [ed. A. R. Braunmuller and Robert N. Watson]. That’s also been very interesting. There’s a kind of out-of-date-ness about editing always. And sometimes that being out-of-date becomes a source of authority, because it makes the edition seem timeless and above such things as mere topicalities. And at other times that out-of-date-ness just seems a bit evasive and to miss the point. Which is slightly how I feel it works in this edition of Measure for Measure. There are so many topical things about the play, it’s quite problematic to know how you’d deal with them, but I’m not sure that this was quite the right way.

The other example I try to use is the Arden Othello, edited by E. A. J. Honigmann. When that book arrives in 1997 it already looks out of date. And not in ways that make it look timeless, but rather that make it look very time-specific. There’s something a bit similar about this edition of Measure for Measure. One of the things I’ve been thinking about while reading the Arden 3 editions is quite what we should do next, or why you would continue to edit in this strange cycle.

This lockdown spring and summer there’s also been such amazing, humbling, eye-opening, shaming scholarship in critical race studies. I’ve been reading and rereading Kim Hall and Ian Smith and Ayanna Thompson and Imtiaz Habib, listening to online events via the Folger and the Arizona Centre, and thinking anew about the teaching and learning I want to do.

~