Paper kingdoms 3: Whitney Trettien

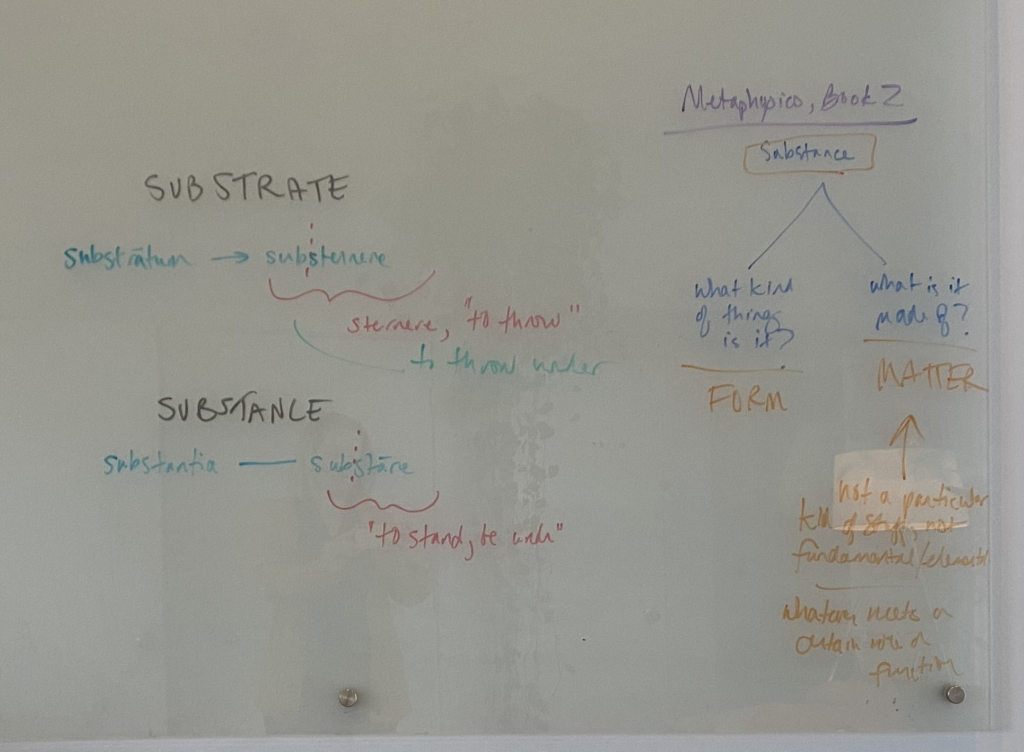

Whitney’s writing room in Philadelphia: plants, a view, and a whiteboard worthy of CSI

Whitney Trettien is an Assistant Professor at the University of Pennsylvania, where she teaches book history and digital humanities in the Department of English. She joined Penn in 2017, following an undergraduate degree at Hood College, where she first began to work with both digital tools and old books and manuscripts. She did this first in an innovative ‘Digital Narratives’ course taught by Martin Foys, then later as his research assistant on a digital mappa mundi project (now realised as Digital Mappa). Whitney then earned a Masters degree in Comparative Media Studies at MIT, and later a PhD in English at Duke University. After graduating she taught for two years at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill before moving to Penn.

I first encountered Whitney’s work through an early article in Postmedieval, in which she traced connections between the material book – its physical qualities, the descriptive language surrounding the codex form – and how writers and scholars thought about plant and animal life in the seventeenth century. Equally importantly, that article also introduced me to the vegetable lamb and the barnacle goose. I love her writing, which is characterised by bold and original thought, an elegant confidence, and a constant drive to unsettle our assumptions about what book history can be. At one point in this interview Whitney said that ‘changing the platforms on which something is said changes what can be said’, and her first monograph, Cut/Copy/Paste: Fragments of History, exemplifies this thought: it’s a hybrid/print digital project hosted by the Manifold Scholarship platform through University of Minnesota Press that’s going to change how we think about early modern readers, writers, books and their publishers. Whitney is also among that tribe of North American bibliographers and book historians who are just – and there’s no other way to say this – cool: great hair, acetate glasses, and quite probably a tattoo of an early modern woodblock somewhere. This is a tribe that puts UK book historians to shame.

Whitney was in her home office in Philadelphia for this interview, which is a spacious and airy-looking environment filled with tumbling green pot plants. We spoke on Skype for a little over an hour, and our conversation is divided into three parts. First, we spoke about the difficult process of moving from doctoral thesis-to-book (1); then we briefly talked about Whitney’s fascinating reading and note-taking practices (2). Finally we talked about how she writes (3), and walked through a case study of her chapter on John Bagford. That chapter is under review for the press at the time of writing, but you can read another of the chapters Whitney talks about (on ‘Edward Benlowes’ Queer Books’) on the Manifold platform. Thanks to Whitney for pictures of her office and of Philadelphia.

1. Thesis-to-Book

INTERVIEWER

You recently submitted your first book, Cut/Copy/Paste, which began as your doctoral thesis. Could you talk through the process of transforming your thesis into a book manuscript?

WHITNEY TRETTIEN

A few paragraphs of the thesis survive! But really this was almost a complete reworking. We don’t talk about the process of producing your first book from your thesis enough with each other, so I appreciate you asking these questions. My dissertation was entirely on Little Gidding. Each chapter addressed some aspect of that community or one of its books. But, as dissertations are, it was also very digressive. In the first chapter, for example, I got obsessed with needlework as a way of thinking about cutting and pasting and publishing in the seventeenth century. That became a monster sixty-page chapter with all these detours into early modern textiles.

After I graduated, for the first two years out, I still had a plan that it would be a Little Gidding book, but I aimed to produce a creative/critical digital project alongside it. I applied for some grants, and got close but didn’t get any funding.

Meanwhile I was looking more and more at the books of this character named Edward Benlowes, who had interested me during the dissertation. And I had just started to think about another character named John Bagford. And then I had this moment where I thought: I could actually expand this, and make Little Gidding one case study, then do another on Edward Benlowes as an amateur book publisher, and then another on John Bagford at the end of the seventeenth century as a collector of book fragments. That expansion produced a nice arc across the seventeenth century, which ended up making the book about fragments, and cutting and pasting, and amateur publishing. So that’s when it gelled for me. At that point I had a plan, and then I had to execute, which became a matter of going to libraries and doing the research to finish the thing.

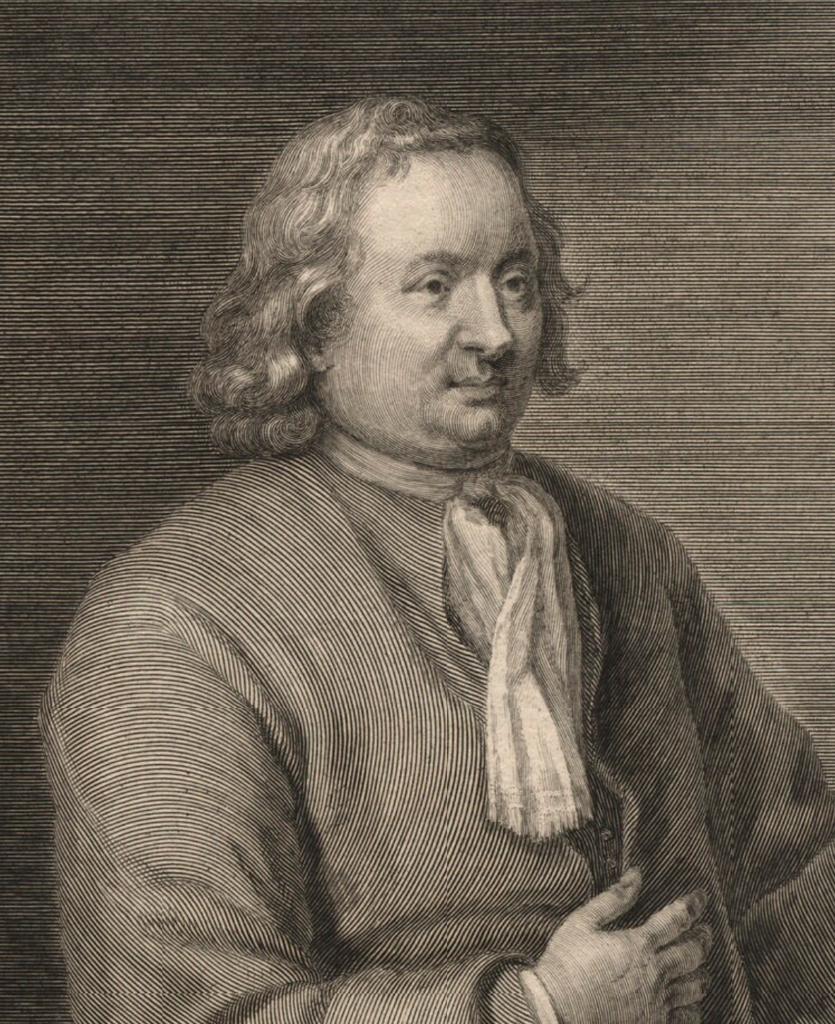

Edward Benlowes (1602-76), from his Theophila (1652)

I wrote the three case studies – Little Gidding, Benlowes, and Bagford – and didn’t write the introduction till the very end. The introduction was a nightmarish process. I had always had in the back of my mind what the book was doing, but putting that material into disciplinary conversations was really difficult. I rewrote it four or five times – it was very stressful! I think that’s common for a first book.

So I talked to other early career scholars and asked them how they had managed it; I read everybody’s introductions a million times and took notes on structure. And in the end I just had to do it the way I wanted to do it, which was to take a slightly more unusual approach. This process was the hardest part of turning my project into a book. You feel as though you’re left over with the vestiges of this earlier project and you’ve got new exciting research, but you don’t know how much of the thing is pieced together in an incoherent, Frankenstein way. You end up constantly asking yourself whether your project has life or not.

I also struggled a lot with how to think and write about periodisation. It’s a seventeenth century project, but I wanted to make bigger points about the present and about the long arc of these books. That took a lot of writing and rewriting. And the chapters that I started from scratch are the best ones, because you get better as you write more.

INTERVIEWER

So part of your post-thesis work was about hiving off work that didn’t belong in a future book?

WHITNEY TRETTIEN

Yes. After graduating I excised some of those digressive chunks to produce articles. I had a mild obsession for a while with Isabella Whitney that had made it into the monster chapter for the dissertation. I turned that into a shorter article for the Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies. The most early-modern section of the dissertation became an article for PMLA on Little Gidding. So my process involved taking the dissertation, squeezing it through some kind of journal article filter, so that little pieces of it went here and there, and then I took some of those pieces and stitched them back into the new work for the book.

I think part of the reason I ended up with this process has to do with the nature of Little Gidding as a subject, especially as the subject of a long-form project. There’s so much to talk about when it comes to this fascinating community. New stuff is out there to be discovered about it, so much that there’s enough to fill a monograph. And in fact Michael Gaudio has done just that in his fabulous book on engravings in the harmonies of Little Gidding. At the same time, though, it is difficult make an entire monograph on one isolated, somewhat idiosyncratic community relate to the broader questions animating early modern studies. How do you scale it to something that – just to be a little bit blunt about it – might be useful to other scholars, who are not at all interested in Little Gidding? That’s one question I had as I moved from the dissertation into the book: how do you move from the representative case study towards something that’s more broadly applicable?

INTERVIEWER

With a community as fascinating as Little Gidding, the things that make your material so compelling and weird become the things that position your work outside a more mainstream set of concerns.

WHITNEY TRETTIEN

Right. So you end up making a point about amateur publishing in this period. Or you use the community as a foil to how we typically talk about the London book trade and make claims about expanding our understanding of book circulation and book-making practices, which is basically what I do in my book. At least for me, though, there’s a limited satisfaction to that argument. I struggle with this problem a lot in my work just now: how to deal with idiosyncrasy; and the case study as a thing that we all work with but that nevertheless has inherent limitations.

INTERVIEWER

Why do you think there’s a limited payoff to the ‘expanding our understanding’ line of argument?

WHITNEY TRETTIEN

If we’re talking about the hand-press period, there was such a wide array of things that you could do with books that every book has evidence of something unusual. Every book can be a case study that speaks to some unique readerly practice, or note-taking practice, or even something entirely non-textual. The book as a place to store spectacles, the book as toilet paper, the book that stops bullets. We can continue to accrue these use cases for early books, but at some point the argument becomes, well, people did a lot of different things with books!

But now we know that. So every book becomes an example of that, and you’re making the same argument over and over again. It’s a problem of book history. For the longest time, book history was tied to textual studies and literary studies and the need to edit. And now it has become its own thing. So what do you do with the book when it’s no longer tied to an author or making claims about a specific text? Should it have its own history? How does that history fit within histories of media, technology, and science, or within anthropology and sociology? Leah Price, for one, has written beautifully on these questions, which we are confronting right now.

INTERVIEWER

Digital tools seem to offer one possible way forwards. Thanks to websites like The Shakespeare Census you can now relatively easily look at all known copies of a particular early edition of Shakespeare, and provide a more expansive framework for developing local arguments.

WHITNEY TRETTIEN

Exactly, digital tools are a big reason these questions are coming up. My colleague Zachary Lesser has recently looked at all the Pavier Quartos he possibly can; we also just had a talk at the Material Texts Seminar at Penn by Liza Blake who has been trying to see all of Margaret Cavendish’s books. I’ve tried to see every extant copy of Edward Benlowes’ Theophila. Certainly bibliographers have always aimed to be comprehensive, but digitization and social media has made locating and seeing alternative copies much easier. Aaron Pratt at the Ransom Centre let me Skype with its copy of Theophila, for instance: this is a completely different experience than sending a query by mail!

Access to high-res photography on our phones and the networked nature of digital files also means that I can take reference photos of every copy and link it to other data. During Liza’s talk, she showed very detailed spreadsheets that she’s been keeping on different binding stamps and so on; in my own work, I store the collation formula of every Theophila I’ve seen in an XML file. This kind of research data only becomes possible with today’s technology, and it’s fundamentally changing the kinds of arguments we can make.

‘What do you do with the book when it’s no longer tied to an author or making claims about a specific text?’: Whitney at work

NTERVIEWER

If you could offer any advice to yourself from a few years ago, when you started the process of transforming your thesis into a book, what would you say?

WHITNEY TRETTIEN

I think everyone’s process is different, but for me: organise your archive. This should have been obvious, but in grad school you’re still learning how to manage a large bibliography and archival materials. Some things you try work out, others don’t. When you pivot to the book project, really consider what worked and what didn’t and develop a system for notes, archival images, tracking copyright and permissions, all of it. Scrub yourself clean of the residue and start fresh.

Also, be realistic. It won’t be the book you would write today, if you were starting from scratch. But it’ll be better than the dissertation, which is a fundamentally different kind of document. It’s more important to be done and move on than to completely remake it. Salvage the ideas and examples that worked and build from there.

Of course, all of this is premised on the idea that you’re graduated and either have or are still seeking academic employment. What to do with a languishing dissertation under conditions of precarity, what kind of advice is needed there – that’s a different discussion.

INTERVIEWER

You mentioned that one of the most difficult parts of writing your book was the introduction, and in particular positioning yourself with respect to disciplinary conversation. How did you solve that problem?

WHITNEY TRETTIEN

I started by assuming the introduction was the space where I would speak directly to my audience and convince them that this subject was worth their time. But that introduces the question: who is your audience? When you’re writing the dissertation, that question is pretty much answered for you by your department or advisors, and how they shape and guide your thinking. For the book, this is a more open question, and it felt like an opportunity to carve out a slightly different space for the work. So I really had to, and struggled to, shed the earlier thinking about what I was supposed to be writing, and whom I was supposed to be writing to; then back up, and think about what I had actually said after all the revisions. That’s when the introduction gelled.

When I was in the midst of the crisis, it was really helpful for me to lean on senior colleagues and mentors. I asked them: should I be more staid in the introduction, or can I experiment a bit, be a bit more weird? They encouraged me to do things the way I wanted to do them, which was weirder. We try to put ourselves in boxes too much, especially with our first book. But you end up writing yourself out of conversations that you could have been a part of.

INTERVIEWER

How did your institutional position influence your approach to your book and your introduction? In the UK at least, early career scholars tend to be acutely aware of the pressure of the REF and the need to produce a book to become eligible for jobs, which can lead to a more conservative approach to positioning your work.

WHITNEY TRETTIEN

No doubt it did. Job security, access to research funding, time, supportive colleagues: these are what enable a researcher’s best, most creative work. It’s also just literally what is needed to complete most scholarly books. I am extraordinarily lucky not only to be employed but that my own position in digital humanities allows for, even demands, a certain degree of risk-taking. I recognise others aren’t so lucky. It seems crucial for folks like me and others hired in these growing fields to use our privilege, to use the opportunity granted us to take risks, to stretch the boundaries and expand a sense of what is possible in scholarly writing and publishing. That paves the way for others to do the same.

INTERVIEWER

Any other advice about transforming your thesis into a book?

WHITNEY TRETTIEN

Be gentle with yourself! The process of moving from dissertation to book for me involved trying to understand how I had been disciplined in graduate school, and then thinking about where I wanted to take that training. It’s about positioning yourself, which was why the audience question was at the forefront in my mind. It’s a hard transition, and you just have to stay true to the things that motivate you. I wrote at the top of my whiteboard when I was in the midst of it: Just Keep Being Dope. Because I kept thinking that I suck, and this is terrible. But we do this for a reason. You’re motivated and passionate about certain ideas. If you stick to those ideas, then you tend to do good work.

~

2. Reading

INTERVIEWER

You have particularly interesting note-taking methods. Could you tell us about them?

WHITNEY TRETTIEN

I take all my notes online. I’m constantly trying to use paper notebooks and failing, I don’t know why. But I have a MediaWiki site that I use for my notes. If I see an interesting link, and it relates to a class I might teach in the future, or a project that’s been brewing on the backburner for a while, then I’ll just dump it in the ‘Projects’ link on my Wiki.

When I read a book, I mark things I want to go back to. Then once I finish reading I’ll go back to those sections and copy out passages onto this Wiki site. That will mostly be quotes from the book. I’ll often remember a word or a phrase from the book, and I like to be able to search for it.

INTERVIEWER

Do you use your notes archive often?

WHITNEY TRETTIEN

I use it all the time. The Wiki is the best thing that could have happened to my note-taking. I keep everything there, it feels very stable, it gets backed up. I have one page in my Wiki on ‘Bibliographic Imaginaries’, for example. If I find anything interesting to do with ‘books’ – maybe an artist’s book that I saw – then I’ll drop a note in there. Then when I need inspiration for a project, I can search through some of the things I’ve kept and find something I can pursue.

The only thing I do by hand that’s important is writing on my whiteboard. I installed that in my home office two or three years ago and it changed my life. I have it divided into four sections: research, teaching, service, and life. I love the whiteboard.

For example I’ve been tracking the etymology of the word substrate, and I ended up drawing a little map the other day (left).

INTERVIEWER

What have you read recently that has excited you?

WHITNEY TRETTIEN

I’ve recently been prepping for a Digital Humanities course, and for that, I’ve just finished Dan Shore’s Cyberformalism [Johns Hopkins, 2018] and Martin Paul Eve’s Close Reading With Computers [Stanford UP, 2019]. I also read Ruha Benjamin’s Race After Technology [Polity, 2019]. These books helped me think a lot about critical algorithm studies and what’s been done in terms of quantitative work recently.

But I always have six books I’m reading at once and I just pick up the one that’s most interesting whenever I want to read. On the Kindle app on my iPhone right now I have Sarah Orne Jewett’s The Country of the Pointed Firs, soothing bedtime reading; a novel by Richard Powers, The Time of Our Singing, which I’m not enjoying that much so I’ve kind of dropped it; Paulette Jiles’ News of the World; a bunch of Clarice Lispector and Octavia Butler stories; and a book called Ebony and Ivy, by Craig Wilder, which is about the Ivy League’s complicity in racism and slavery.

~

3. Writing

INTERVIEWER

Could you talk us through the anatomy of your chapter on John Bagford? How did it start, and how did it come together?

WHITNEY TRETTIEN

First I searched for everything that has been said about Bagford. I’ll gather that material into one place, and then read it all: secondary stuff, going back to the eighteenth century. At that point I have an arc of the scholarship in relation to Bagford. It’s easier with figures like Bagford because there’s not a lot that’s been said, but I did the same thing with Little Gidding and with Edward Benlowes.

John Bagford by the engraver George Vertue (1728). Credit: National Portrait Gallery

Then I think: well, this person has been imagined by researchers in this certain way. Then I try to come up with a caricature of that figure. Then I’ll go to the archival materials themselves and ask: does this caricature match up? Where does it match and where doesn’t it match? That basic model was the genesis of all the chapters in the book: thinking through how people had been seen, versus what their stuff tells us about them.

After looking at the materials, I’ll track their afterlives, which I think is really important for book history. You’re never looking at the thing in the seventeenth century; you’re always looking at the ways it has been remade. I try to understand how archival pressures have shaped my own relation to the stuff.

Finally I try to answer the ‘why this?’ question. I can

almost never answer this till the very end; I never start with why. I just have a hunch that I pursue, and then I finally find out why I’m interested in this material. I’m always just thinking that something is here… I think of it like puzzle-solving. My masters degree was in media studies, studying with people who work in anthropology and ethnography, and I still often think about my work as ethnographic in some way.

With Bagford, the answer to ‘why’ came down to the fact that he’s a working class bibliographer. Bagford started off as a shoemaker and only later became a book agent, selling rare manuscripts to collectors like Hans Sloane or Samuel Pepys. He also became a collector himself, and his collecting habits were absolutely shaped by his former work as a shoemaker. He was a person who made things with his hands; and his lack of formal education meant his mind was more flexible, less disciplined than his contemporaries. He could see the value in scraps of leather bookbinding, recycled manuscript leaves, stuff that others discarded. Of course he could! It was elite bibliographers like Pollard who couldn’t.

INTERVIEWER

Is there any particular rhythm to your writing day?

WHITNEY TRETTIEN

Yes. I do well in the morning and in the evening, and I utterly hate the middle of the day. When the sun is streaming in my windows – I can’t write at all. There’s a really great Margaret Cho essay in Live Through This, which is a collection of essays by women artists on creativity and depression, and in it she says that 2pm is the worst time of the day. She’s all, ‘I wake up, I have my orange juice and my coffee and feel great and can get so much done. And then 2pm comes and the day is never going to end, and it’s too sunny, and I don’t know what to do with myself.’ That resonates with me so much! Then the sun goes down and I can put on some afrobeat and get back to work. Get back to the crepuscular zone, the gloaming. If I open my laptop at seven I can enjoy another two hours. I go to the gym in the middle of the day, or go for a walk.

INTERVIEWER

Do you write in any particular spaces?

WHITNEY TRETTIEN

I can write in most places. I try to squeeze some in on busier campus days. I think that’s the key: write whenever you can, and don’t wait for inspiration to strike. I write a lot in my home office, though, which I love because it has a standing desk that I can move up and down. And a whiteboard, and a beautiful view of the city. I feel comfortable here. My one thing when I moved to Philadelphia was that I wanted to have a space where I could have a home office. And I have plants all over the place – I like to have plants around when I write.

‘I write a lot in my home office. It has a standing desk, a whiteboard, and a beautiful view of the city’: Philadelphia from Whitney’s office

INTERVIEWER

Is writing a struggle for you?

WHITNEY TRETTIEN

It used to be more antagonistic, but after I graduated I read some books on academic lifestyle. A lot of the advice is lame, but every single one of them emphasised that you just have to learn to write when you can – don’t wait for creativity to strike. I tried to get into that habit. So sometimes it’s a good day, sometimes it’s a bad day, but just keep the pace up and don’t wait for the summer to do a tonne of work. Keep a slow and steady commitment to thought.

INTERVIEWER

Do you re-write very much?

WHITNEY TRETTIEN

Yes. But I re-write as I write. So I might spend a week on two paragraphs that are bothering me. I won’t get a first draft, then go through and make a second draft, and so on. I’ll try hard to make the paragraph do what I want and then move on. The thinking for me happens on the page. I might know roughly where I want to go, but really I almost never know what I’m going to say when I start a paragraph.

Then once I’ve figured out what I want to say I have to re-write it, and then re-write it again, and so on. Is it Peter Stallybrass who has an article claiming there’s no such thing as thinking, only working? I feel that strongly. You have to work, and when you do, the ideas will eventually gel. When I’ve got a nice draft I’ll print it out and read it through, and I might make some changes – though they’re usually small scale, not structural.

I write in Google Docs. That lets me keep version histories of everything, but it also means I’m not tied to one computer.

INTERVIEWER

How much time should it take to research and write an article?

WHITNEY TRETTIEN

The fastest I’ve ever done it was last summer. I needed to start and finish the Bagford chapter. I went to the British Library for a month. I went every day they were open, for most of the hours they were open, and I sat there with the materials, and I was able to get a 25,000 word chapter done. That was the fastest I’ve ever done it, and I was amazed that I got it done.

INTERVIEWER

We usually gather archival matter then scurry back to write it up elsewhere. Did writing with the material in front of you make a difference to your thinking in other ways?

WHITNEY TRETTIEN

Exactly. Usually I’ll take all my notes on an interesting object and then come home and try to turn it into something. This was the first time when I’d actually written an entire piece while in front of the materials it was about. It was fabulous: I could look at the manuscripts upstairs, then run down to the rare books room to check a source. It made all the difference to my speed of writing to be with the objects. It also enabled me to see connections where I never would have otherwise, which is absolutely necessary for Bagford. His materials are incredibly diffuse; piecing the story together from reference photos would have been impossible.

INTERVIEWER

Your book is structured around people: John Bagford, Edward Benlowes, the Little Gidding community. How helpful are biography and personality as variables for your thinking?

WHITNEY TRETTIEN

I was especially drawn to personalities for this project, but in general personalities and their books fascinate me. One of the books on my nightstand is a biography of Belle da Costa Green, who was the first librarian at the Morgan Library. She was also a person of mixed race but who passed as white in the early twentieth century. And I’m fascinated by people like her, who worked with books and lived in ways that defied social convention. How did they spend their time? What did they read? In what spaces did they write or do their work? What moved and motivated them?

INTERVIEWER

Do you know when you’re finished with a research topic?

WHITNEY TRETTIEN

I feel sick of things! I feel sick of Little Gidding. There’s more to be said about Little Gidding, but it won’t be by me.

INTERVIEWER

Your work explores digital publishing formats in brilliant and exciting ways. Your draft chapters online at Manifold Scholarship are replete with material that illustrates or complements your prose: images; a video introduction to Phineas Fletcher’s The Purple Island (1633); a graph counting the number of people involved in producing Humphrey Moseley’s books. Is this the future of academic publishing, do you think?

WHITNEY TRETTIEN

I’m trying to make the case that it’s one future for book history, at least! Changing the platforms on which something is said changes what can be said. That’s one of the key arguments of digital humanities, and work done by pioneers of digital publishing, like Tara McPherson, or more recently Janneke Adema, Marisa Parham, and others too numerous to mention. So when it comes to using digital methods, I’m always asking: what new histories could we see if only certain objects were placed in the right context? If only you could comparatively visualise formats, for instance? What if you could see some neglected books as part of a broader social network of publishing, or mapped with other items? How would this shift our perspective on the past?

I mentioned starting my case studies with a hunch. Digital tools and methods help me pursue those hunches and discover precisely what makes these people and their books interesting, and worthy of our attention.

INTERVIEWER

Can you say anything about the challenges introduced by your approach? For example, how do you decide what does and doesn’t need including as a digital asset? Where are the boundaries of this new work?

WHITNEY TRETTIEN

The biggest challenge has been something really mundane and frankly stupid, and that’s navigating copyright. Most books I work with are in the public domain, and I own the photographs I take of them. But many research libraries still enact tedious policies dictating what you can and can’t do with these, your own, images. Some of these policies are of dubious legality, and wouldn’t stand up in court, but of course you still don’t want to annoy librarians and curators who have been so helpful to you by disseminating images without permission. Other libraries offer digital images but have vague policies about use, or require written permission, or charge fees. When you’re working with books and images from dozens of different libraries, permissions become an unruly beast. Can you imagine if all these digitized cultural artefacts were just – available for anyone for non-commercial use? I feel really grateful to institutions like the Folger Shakespeare Library that have open policies with clearly posted guidelines. It frees up so much work.

INTERVIEWER

How important is your academic community to your research process?

WHITNEY TRETTIEN

Increasingly important. I was on leave for the calendar year of 2019 and I was struggling halfway through that year with writing and thinking. Only very belatedly did I realise that part of my problem was because I missed the daily interactions of colleagues and lectures and teaching. I get so much intellectual energy from that.

INTERVIEWER

Are you ever short of ideas? And if so how do you navigate that problem?

WHITNEY TRETTIEN

I do feel like that, yes. I often have four or five things cooking at once, and I struggle with knowing how to scale up something into a bigger project. For example, right now I don’t know what the next book will be about, but I’m just writing a few articles that get the ideas down on paper. Maybe something there will cohere around a bigger topic.

INTERVIEWER

When is an idea enough of a thing to warrant an article or a chapter?

WHITNEY TRETTIEN

I imagine articles to speak to a very scholarly audience. So for me, an article needs to intervene in a field conversation – just an object is not enough. It has to be something that intervenes. So right now I’m working on something on media studies and book history that looks at how people in both fields are using words like ‘format’, and exploring how we’ve misused these terms. Here I can offer some clarity to a conversation, which makes it worth writing as an article. But short chapters can be case studies, something that’s more fun. You can say a modified version of something you’ve said before.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have a favourite font?

WHITNEY TRETTIEN

No. I write in Times New Roman because it’s invisible to me at this point. If I used something fancier or different then it might become visible and that would worry me. I’ll admit I like Georgia.

INTERVIEWER

Are there any rituals you have that help you write?

WHITNEY TRETTIEN

If I’m writing I feel like I have to smoke. I’m trying not to because I’m not really a smoker! But for some reason, sitting at the window and smoking gets my brain moving. So now what I’m doing is I sit there with my LaCroix, and I drink bubbly water and that can help me get going. I always think I need to put on music – afrobeat, or jazz, or something without lyrics – but in fact I find it distracting. So I’ll put it on, listen to five minutes of it, and then turn it off to start writing.

~