Paper Kingdoms 7: Jeffrey Todd Knight

‘As if the little well-ordered world of my screen could provide solace from the chaos of elsewhere’ – Jeffrey Todd Knight

Jeffrey Todd Knight is Associate Professor of English at the University of Washington in Seattle, where he has worked since 2011. Jeff grew up in Kentucky–‘my family are hill people’–and went to Northwestern University for his graduate work, where he earned a PhD in a department that included Wendy Wall and Jeff Masten. He is currently working on a handbook to book history for the Arden Shakespeare Fourth Series entitled Shakespeare on the Page: Texts, Books and Readers.

Jeff’s book, Bound to Read (Penn, 2013), was the first book I reviewed as a graduate student. I looked back over my notes for that review while editing this interview. Twenty-seven pages of excitable typing about Myles Blomefylde, John Lilliat, the Pavier Quartos, William Pugh, strange hybrid books that defy tidy categories, and perhaps above all, Sammelbände, the multi-volume bindings that have become so prominent in early modern studies. From those notes:

‘Pugh often used up to ten folio-sized pages to catalogue a single book. He was sacked after ten years for not making enough progress’

‘Consider the term C&P’

‘Catalogue as palimpsest of catalogue-mutation’

‘Quentin Skinner? Doctrine of Coherence?’

‘Pigman, Greene, Cave, Crane, Moss’

‘Spenser’s practical knowledge about basket-making’

Notes like this supply the materials for a strangely personal archaeology. Reading them now, I’m reminded of Eliot’s lines from Little Gidding in which the poem’s speaker meets ‘a familiar compound ghost / Both intimate and unidentifiable’. What shines through those notes is how inspiring I found Jeff’s work, just as today I see graduate students take inspiration from his ideas all the time. He has written on books as furniture, sewn repairs to printed pages, and the current challenges around the scale of book history among other topics. I’ll read anything he publishes, as I would for Helen Smith or Adam Smyth or Zachary Lesser or Juliet Fleming and a handful of other figures, and I’m always struck by Jeff’s brilliant ability to air out the conceptual interest of the close material work he does so well. I read him for his constant pursuit of the larger stakes of an argument and his interest in what it is that we are all actually doing in book history at this moment. I also read him for his sharply turned prose–it was a surprise to me when he said in our interview that he never thinks about style.

The conversation below is in three parts. In (1.) Bound to Read, Jeff talks about how that influential project came about and the process of moving from thesis to book. Jeff’s thoughts on (2.) Writing are particularly important for his honesty about its difficulties as well as its pleasures; finally in (3.) State of the Field we speak briefly about the relationship of book history to institutional trust and the need for us to develop a new common language to generalise and make portable the discrete studies that characterise much of the work in early modern studies at this moment.

My thanks to Jeff for finding time to talk and for supplying images of his workspace and, especially, of his dog.

(1.) Bound to Read

INTERVIEWER

How did the project that became Bound to Read begin?

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

It began while I was working towards my doctorate at Northwestern. I finished coursework and got this idea that I needed more bibliographical training. There were a few local grants I could cobble together to pay for tuition and travel, so I looked around online and found this MPhil programme at Cambridge that was very texty. Bibliography, manuscript codicology, English and Latin palaeography in under a year. That kind of training is more common in the UK system than it is in the US — at Cambridge we set metal type and stitched books, which is totally alien to how we think of advanced literary study in the states.

INTERVIEWER

How was your doctorate going?

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

At the time I had a dissertation prospectus written that was, frankly, terrible. I think my committee was too nice to tell me that.

INTERVIEWER

What was that original project?

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

I can’t remember the details but it had something to do with the history of information. I was very taken with the poststructuralist idiom, as I think lots of people were in the early 2000s, and I remember that it was highly theoretical.

When I reflect on it now, I think I probably wasn’t ready to write and I was hiding behind a metalanguage that I could use convincingly enough. It would have been a kind of wheel spinning dissertation. The danger with this type of project was in becoming an exercise in methodological self-reinforcement, whereby the project just argues the value of one particular way of looking or reading.

Against that theoretical mode I think part of me has always idealised the ethos of discovery in scholarship, where new knowledge is being produced or found or unearthed. That set of feelings could have influenced my decision to go and seek this very hands-on material text training in Cambridge; it was the opposite of theory.

INTERVIEWER

So you went to the MPhil.

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

Yes. And at Cambridge I took a lot of skills-based classes, and through a great group of tutors in the English faculty I became introduced to people in the libraries who were thinking about books in ways that I couldn’t even conceive of. David McKitterick, for example, and Elisabeth Leedham-Green, who knows everything. I had lunch with Elisabeth a few times and remember asking very clumsy questions about the physical make-up of books. She was always generous about correcting me and giving me tips on where to look for new evidence.

The key thing I noticed was that the collections at a place like Cambridge look different from similar archival collections in the US. With a few exceptions, our collections in the US are much more uniform and rebound. Margins are cleaner. The books look like they should be in a nineteenth century gentleman’s library. Books do not look like that at Cambridge, especially in the colleges.

So I started reaching out and talking to people at the Parker Library and St. John’s, and then at Oxford and York and Glasgow. Eventually the project that became Bound to Read came together in the complete opposite way of how I had assembled my proposed PhD project. For the new project, my process was inductive. I started with the particulars and looked for a story to tell about the material, instead of beginning with a high-level conviction and working downwards to make things fit.

~

‘I started with the particulars and looked for a story to tell about the material, instead of beginning with a high-level conviction and working downwards to make things fit.’

~

INTERVIEWER

You had paused your doctorate to take the MPhil, so then you needed to return to the programme at Northwestern.

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

I did. I trashed my earlier dissertation prospectus and wrote the new dissertation in two years. I had moved to New York where my partner had just started at NYU, so I was away from my graduate programme and relied on places like the New York Public Library and the Morgan Library, and university special collections in the area. Those libraries gave me helpful comparison points.

INTERVIEWER

How was the process of transforming your thesis into the book?

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

I didn’t change the thesis very much to become the book. I think I was lucky to have had enough material and to have done it passably well the first time. I remember one of my advisors, Wendy Wall, telling me in my defence: ‘this is a tenurable book’. After that, I more or less left the bulk of the manuscript, though I did think strategically about the process of publication.

INTERVIEWER

In what way?

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

I held the book back initially till I was on the tenure track, so that it would count for something when I published it. And getting on the tenure track took me a few years. So in that time I read some more and touched up the introduction. I deleted a short chapter at the end that I thought didn’t fit and I added one on collected works. That chapter [chapter 5: ‘The Custom-Made Corpus’] had originally been a seminar paper that I had written a few years before on Chaucer, and at the time of writing I hadn’t realised it worked with my thesis. But later on I saw that it seemed to belong to the project. Then I just sent it off.

INTERVIEWER

That was an amazing compliment to receive at your viva from Wendy Wall.

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

Yes. Wendy is an incisive reader of student work and doesn’t really flatter people. At the time it sort of blew me over and I still don’t think I’ve fully recovered from that moment.

INTERVIEWER

What do you mean?

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

Partly it’s just the approval coming from someone whose work you’ve admired and emulated all those years. And then it’s the shock of having made something that someone sees as valuable in a longstanding scholarly conversation. It seems so difficult or impossible to do that when you’re a student in a historical field.

So much of what we do at that stage is strain to get a piece of writing out there that really doesn’t say much–to publish so we don’t perish. I think Wendy’s comment helped me feel like I had done something real, if that makes sense.

‘One of my advisors, Wendy Wall, told me in my defence: ‘this is a tenurable book’… it sort of blew me over and I still don’t think I’ve fully recovered from that moment.’

INTERVIEWER

That makes sense. At one point in your book you quote Philip Sidney’s ‘one Cyrus to make many Cyruses’ line, and your book has made many Cyruses! It drew our attention to Sammelbände studies in ways that continue to grow. You brought new interest to the ‘ghost’ as a category of bibliographic evidence, which now features prominently in Zack Lesser’s forthcoming book on the Pavier Quartos. But maybe more than those particular features of the literary record, your book also urges us to be alert to the unit of interpretive context as a significant variable in our thinking, and that sensitivity to units and categories seems an important current concern of the field.

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

Thanks! A lot of what the book had to say to literary critics came down to that concern with the default unit of study. We inherit these powerful models–the New Critical well-wrought urn, the single standalone text, or the historicist synchronic context model–that leave so much unexplored in the middle space between writers and readers. The project attempted to bring something from the space of libraries and archives into the literary field, and to use the physical book object to recalibrate what we read and how we read.

Sammelbände research involves specialist knowledge that almost never travels into literary studies, but should. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been at a conference or on a panel session and I’m listening to a library or archives specialist and utterly amazed at all they know that we don’t. I saw the binding specialist Mirjam Foot a few years ago at an event where I was sitting in the audience with Alexandra Gillespie–who by the way was doing Sammelbände stuff before I was–and we were both just floored by the depth of her expertise and how applicable it was to the literary questions we’d been asking. It seemed like every other sentence could have been the germ of a case study or article in our field.

INTERVIEWER

How long did it take you to secure a permanent job?

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

I went out on the job market for the first time in 2008 when the first financial crash happened. At that time, so many jobs were advertised but then cancelled. And that time around I ended up taking a postdoc in Michigan, where I was for three years. During that time I applied to lots of jobs, but I was being somewhat selective, which people don’t have the freedom to do now because of the state of the market. In the end I got my job here in 2011.

INTERVIEWER

What were the significant challenges of the process of transforming your thesis into the book of Bound to Read?

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

Well, the manuscript had two readers. One pressed me on big picture issues and the other on smaller things. I had to go back and get a handle on the historiography of bookbinding, which at the time was mostly focused on antiquarian fine bindings and provenance. I’d made a lot of terminology mistakes that needed to be corrected.

Figuring out all the rituals involved in reaching out to presses also took a while. The big question for me was whether to pursue publication with Cambridge or Oxford, which are ironclad for tenure cases in the US, or with a smaller press like Penn whose books are more affordable and usually better in our field, but which doesn’t come with the same promise of advancement or mobility. I was okay with the trade-off, and Penn was great to work with.

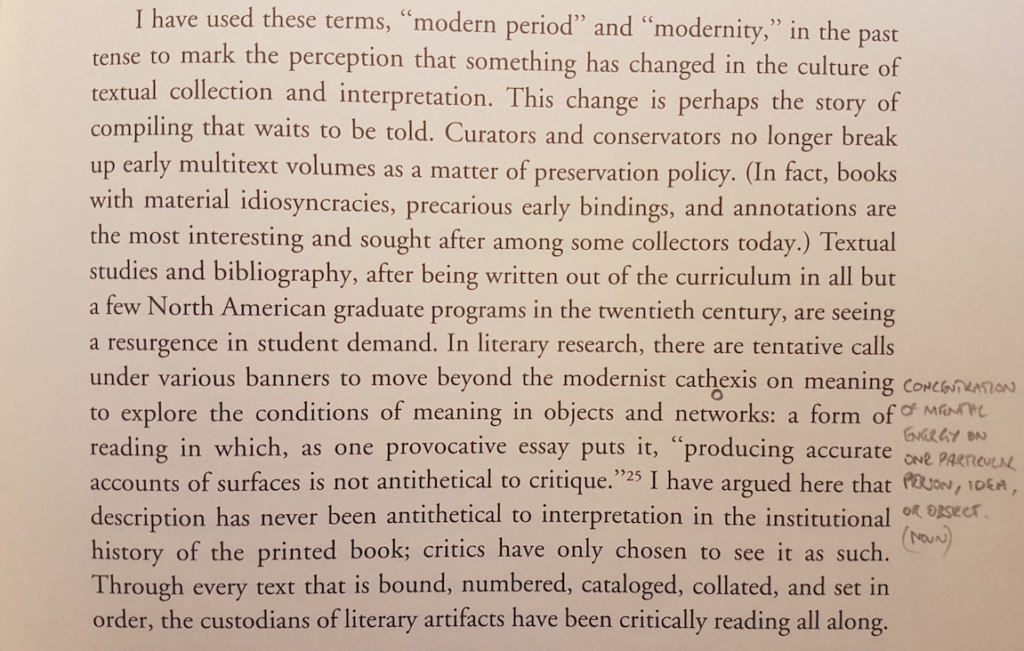

The conclusion also gave me difficulty. I was trying to push myself into that realm of generalisability beyond the details and case studies, and that’s hard to do in a project that’s so adamant about singularity of objects. I remember staring at the last paragraph, trying to get it right, all the way up till it was due at the press. I kept fiddling with the language in those last sentences, and ultimately I let Sharon Marcus and Stephen Best have the last word. I gestured towards surface reading, which was making waves at the time, and I ended it there. I was never very happy with the conclusion.

How should a book end? The final page of Bound to Read, p. 187, tinkered with till due at the press.

INTERVIEWER

Tricky things to write.

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

Conclusions are hard. They’re hard even in small-format pieces.

INTERVIEWER

But thinking about portability and the future life of the work seems the right ethos.

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

I think so. A lot of the difficulty there comes from the way we were trained in the nineties and the early 2000s. We weren’t trained to generalise.

INTERVIEWER

They’re still difficult even for those of us who trained later! What lessons did you learn from writing Bound to Read that you would pass on to graduate students thinking about writing their first book?

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

The thing that helped me the most was talking to people outside the field and discipline. The clumsy questions and emails to librarians and archivists led me to connections I wouldn’t have made otherwise.

‘The thing that helped me the most was talking to people outside the field and discipline. The clumsy questions and emails to librarians and archivists led me to connections I wouldn’t have made otherwise.’

At Michigan I was required as part of my fellowship to meet bimonthly to discuss research with colleagues who were scientists, social scientists, and artists, among other things. Those kinds of interdisciplinary conversations really clarify what is interesting about a project and what might have traction beyond one’s dissertation committee.

~

‘In grad school I had a pretty elaborate system of self-reward involving snacks and trips to the art museum. Now I have a dog.’ – Jeffrey Todd Knight

(2.) Writing

INTERVIEWER

Could you characterise your writing process?

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

I can try. I have very bad writerly hygiene. I know all the things you’re supposed to do, and I don’t do them. I know that in order to write I need to draft; but I don’t draft. I usually write from the first word to the last word and that tends to be a very slow and painful process. The only time I revise is when I’m asked to revise by a reader. Or in response to someone who I’ve asked to read the manuscript, like a friend or a colleague. I’m never able to revise on my own.

INTERVIEWER

Do you mean that you continually rewrite as you go? Or that when the words emerge they will very rarely be changed at all?

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

The first thing! For articles and chapters I start every day by going back to the beginning. So, if I’m working on a paragraph on page twenty-six, the next morning when I get up to write I go back to page one and I read through the entire piece. And I’ll change things as I go, so the early portions of a piece of writing are always more worked over than the later portions.

So I guess that is a species of revising, it’s just an oddly distributed and probably unhealthy one. I hear people say that they just put their thoughts out on paper for a first draft and they go back through for a second draft to clean it up after they have some distance and perspective. I’ve never been able to do that.

INTERVIEWER

How did this method of writing evolve?

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

Honestly it’s probably a little pathological. There’s something about it that feels obsessive. I need things to be perfect before I can get myself to walk away from the laptop. As if the little well-ordered world on my screen is going to provide solace or defence from chaos elsewhere.

There’s always a point of diminishing returns. I know that when I finally walk away at the end of the day the last stretch of writing has been less productive than it was earlier in the day. But I’m rarely able to pull myself away from it. I had to finish the thought or the paragraph of whatever I was working on.

I have a similar set of responses to the idea of having a writing schedule. I know that I’ll be most productive if I get up in the morning at six o’clock and write for two or three hours without looking at the news or checking my email. And then I can do other things throughout the day. But mostly I don’t live up to the ideal. I get up and twenty minutes later I’m on the New York Times website fretting about something that Trump did or something about the pandemic. Or I’ll check email and be pulled into a service obligation. So usually I end up having to write till ten o’clock at night in an unproductive state of trying to get a paragraph to look perfect.

INTERVIEWER

What are the main emotions that you associate with writing?

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

Writing brings me joy even though it’s painful. When I’m writing, I’m working out an unformed thought.

‘Writing brings me joy even though it’s painful. The rules of grammar and syntax and the fixed lexicon of the language forces me to put my thoughts into some kind of sense.’

The rules of grammar and syntax and the fixed lexicon of the language forces me to put my thoughts into some kind of sense. And that becomes a recursive process: it clarifies my thinking which then clarifies my writing and so on. It feels really good to do that.

When you can step away from something and see that a beautiful and complex thought has been externalised — that brings me a lot of joy.

INTERVIEWER

It will be helpful for people to learn that successful academics with important books still struggle with writing. How do you cope with the more painful aspects of the writing process?

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

In grad school I had a pretty elaborate system of self-reward involving snacks and trips to the art museum. Now I have a dog. Dogs are hypersensitive to humans’ moods, and need things at regular intervals, so they keep you from falling too far into an emotional abyss. It’s banal to say but it really is essential to have some external, scheduled thing like dogs or exercise or meditation that gets you out of your head every so often. Full paragraphs come to me on dog walks or on the Peloton after I’ve struggled in front of the laptop for hours.

INTERVIEWER

Where does the bulk of the intellectual labour sit in your writing process? Do you plan much beforehand, or think as you write?

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

Almost all the intellectual labour is in the writing itself. I keep planning documents which are basically essay ideas on my computer desktop and over time I add to them when I go to libraries or talks. Eventually there’s enough substance to turn an idea into a piece of writing, but it’s never more than an intuition or sketch at the start.

INTERVIEWER

Once you are through your first draft, what might you do? Do you share your writing with other people? And what value does this process of sharing your work have?

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

I’ll send my writing to someone, yes. This is particularly important for me because my process is so solitary. I can become my own echo chamber. I have a senior colleague who I turn to quite frequently. He’s extremely critical and does not pull his punches almost to the point of recklessness. He’s someone I can go to who can say: ‘this is crap, this isn’t working’ or ‘this is promising’. I try to find people like that.

My wife is a scientist and a very matter-of-fact writer who also doesn’t pull punches, so I run things by her as often as I can. We think in completely different ways, so her input helps me to be clearer and more diplomatic in my prose, or to see something about my assumptions that I didn’t notice before.

INTERVIEWER

Harsh feedback is so valuable but can also be challenging. What’s the difference between a brutal reader who squashes you and brutal reader who is valuable?

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

It can be paralysing if you find the wrong reader. I’m in the process of assuming the editorship of the journal Modern Language Quarterly which is housed at my university. And in that role I see a lot of reader reports. I’m a big believer in peer review, but sometimes it can enable a certain sadistic mode of critique. It seems like it’s usually someone who has an axe to grind or is too close in some personal way to the material being written about.

‘Peer review is routinised generosity. Nobody gets paid for it. Some readers donate their time to help an author assess and develop an idea, but some use the opportunity to reinforce a power differential or lash out at a perceived threat. Just occasionally, you find readers who are harsh but who are wholly in your piece, thinking with you.’

I think the key variable is whether somebody is reviewing for the author or for themselves. Peer review is routinised generosity. Nobody gets paid for it. So you have readers who donate their time to help an author assess and develop an idea, but you have some who use the opportunity to reinforce a power differential or lash out at a perceived threat. You occasionally find readers who are harsh but who are wholly in your piece, thinking with you. My writing benefits the most from that kind of review.

INTERVIEWER

Might your revisions be large?

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

Yes, they might be. My writing is very tightly wound, so when I get substantial feedback on a piece I have to go in and cut it open in places, and it can take a while for the wounds to heal in a way I’m happy with.

INTERVIEWER

It sounds as though your prose is particularly carefully sculpted. But your writing on the page is never stodgy, so do you think consciously about letting in air and light and space to loosen it up?

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

More air and light and space are on my wish list. I have three or four pieces for non-academic audiences that I know I need to write. And for those I would love to develop a more easy-going style. I hear people say that blogging or microblogging can help to loosen up one’s writing, but I’ve never tried.

But I really value clarity in academic writing. And this value emerged in ways that relate to my reading process: I learned at a certain point not to blame myself if it takes me two or three times to understand something I read. I’m teaching Frederic Jameson’s The Political Unconscious right now to my undergraduates and I’m seeing them go through this same thing. They take the blame on themselves for being confused, when in fact it’s totally Jameson’s fault. He’s not imagining what it would be like to be a reader on the other side of this wall of text. So perhaps my writing comes out with a bit more air and light just because I can’t stand that kind of crabbed, high academic style that is so imperiously removed from reader experience.

INTERVIEWER

How do you think about style or literariness in your academic prose? Using metaphor, for example.

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

I don’t think about it much. When I look back at things I’ve written and am happy with something then I can assess it at the level of style. But not while I’m writing. I wonder if this is unusual, actually. Last summer I was developing a course for graduate students in my department on academic writing, and I was looking through all these guidebooks on how to publish journal articles. Seeing how attentive these books are to stylistic tropes–how you craft a metaphor and where it belongs, for example–that surprised me. I’ve never consciously considered it. But I’m very attentive to style in other people’s writing.

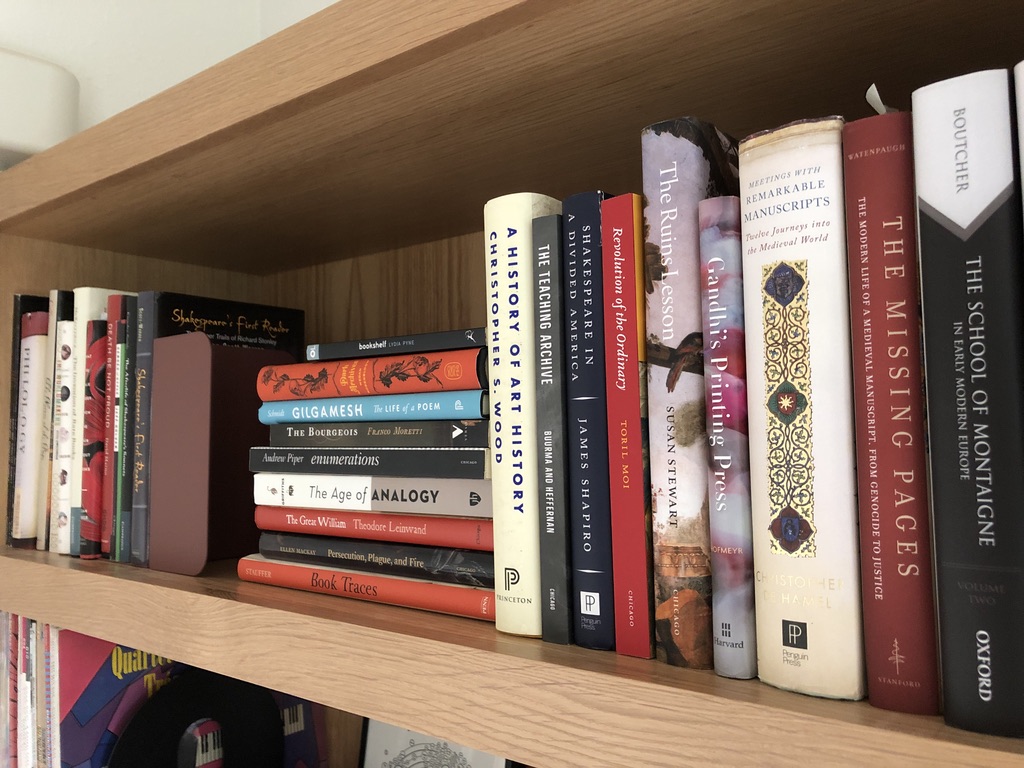

The books of a book historian: diachronic and material interests running through the top shelf

INTERVIEWER

Which academic writers do you particularly admire?

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

To me, Jennifer Summit’s Memory’s Library [Chicago, 2008] is the Platonic ideal of an academic monograph. It’s so elegant in how it’s organised around pairings of library sites with literary figures so that each chapter has stakes and speaks to multiple audiences.

Style-wise I’ve learned the most from reading my grad school advisor, Jeff Masten, followed probably by Carolyn Dinshaw, Mark McGurl, or Deidre Lynch. I’ll read anything by John Guillory–not so much for style but because of the way he grounds his concerns about literary history and theory in the real world of public discourse.

INTERVIEWER

Do you feel that your writing has developed since you wrote your thesis?

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

I’m much more careful about phrasing and logic and probably terminology than I was before. I’m more aware of how difficult it is to master something, whether that’s a volume of secondary literature or a physical object in the archives. So I’d guess my writing comes off now as a little more circumspect, maybe less adventurous, but more consistent and substantive than it was before.

INTERVIEWER

In some senses that journey sounds like the opposite of a different writerly stereotype, which is of the overly defensive and cautious doctoral scholar who buttresses each utterance with manifold authorities but grows more confident as their career progresses.

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

That’s true. I hadn’t thought about that. There are a lot of senior scholars whose writing gets more cavalier over time, too. But midcareer is a qualitatively different stage from the rest of the academic life cycle. It’s hard to know what is a real lasting change and what’s just a lull.

INTERVIEWER

In a world with time machines, what would you tell yourself now if you could go back and visit yourself during a difficult moment of writing your first book?

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

Find balance. Spend less time worrying about getting an idea or phrase just right and more time reading widely or developing relationships, which make your work better. Don’t take rejection personally. The first piece I ever sent off for publication was rejected three times before it found a home somewhere, and now it’s my most cited piece.

~

‘Find balance. Read widely, develop relationships which make your work better. Don’t take rejection personally. The first piece I ever sent off for publication was rejected three times, and now it’s my most cited piece.’

~

INTERVIEWER

In ten years time what do you hope will have changed about your writing, whether an aspect of style or of practise?

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

I hope I’ll be writing more public-facing work. Work with a broader audience. I’m going in that direction now with a book I’m writing and I’m enjoying the challenge. I’m looking forward to my role shepherding others’ writing into print as a journal editor. It could be that my quasi-obsessive energies are better spent that way.

~

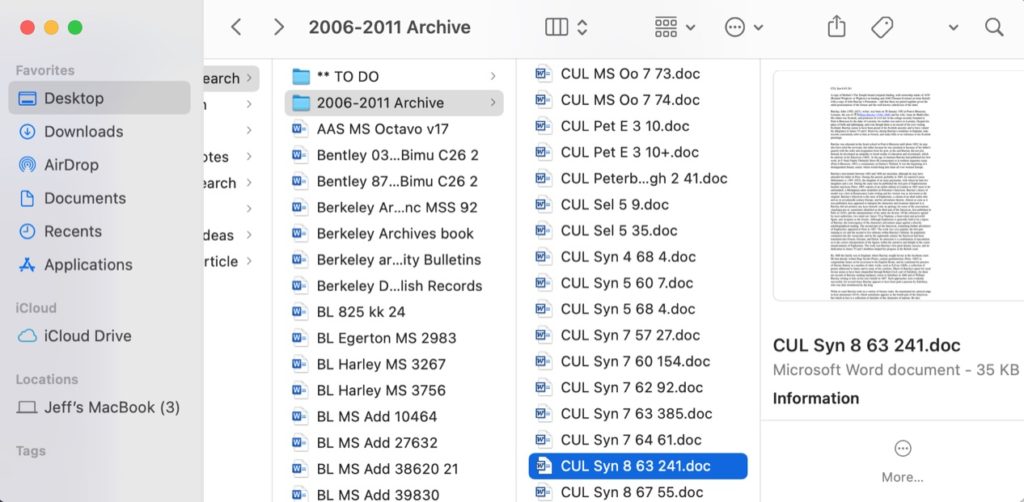

A digital Sammelband? The Bound to Read archive

(3.) State of the Field

INTERVIEWER

What do you see as the current concerns in Sammelbände studies and book history?

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

I think we’ve gotten really good at this particularist mode where we explore a single curiosity in depth or use an anomaly in the archive to push back against some long held critical idea that needs rethinking. There’s a lot of value to that mode of work, but it can’t continue for ever. It’s undertheorized, for one thing. And the individual case studies aren’t portable. They don’t generalise to things people care about outside the field.

The bigger problem is that the institutional basis for this kind of work is eroding. With the humanities shrinking, pretty drastically in some places, the extensive approach to research, where you’re fanning out and focusing on this wide range of particulars, isn’t going to be sustainable for long. I think the biggest challenge at the moment is figuring out what this kind of work is going to look like as departments and faculties get leaner and less historical, and as the academic labour crisis continues to chip away at opportunity.

INTERVIEWER

What have you read recently in early modern studies and book history that you’ve enjoyed?

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

I love this trend of tracing the diachronic pathway of one particular work: Zack Lesser’s Q1 Hamlet book, Emma Smith’s on the First Folio, or Jane Kingsley-Smith’s Afterlife of Shakespeare’s Sonnets [Cambridge, 2019]. Have you read Peter Murphy’s The Long Public Life of a Short Private Poem [Stanford, 2019]? This goes back to the idea of Sammelbände studies and the proper units of literary study. Murphy’s book is about Thomas Wyatt’s poem ‘They Flee From Me’. The whole book is just about that poem. The opening lines are a description of the first manuscript witnesses and it moves forwards through the life of the text, going through its permutations in miscellanies and anthologies, its adoption by the practical critics and New Critics in textbooks, its reinterpretation by the New Historicists, and ending with a coda on the future of the humanities and higher education. It’s incredibly touching and energising, and an important stylistic experiment.

Other things I’ve read recently in the field and enjoyed: Megan Cook’s The Poet and the Antiquaries [Penn, 2019], which is beautifully written. I just finished Jason Scott-Warren’s Shakespeare’s First Reader [Penn, 2019]. That’s another one of these monographic experiments that I find so energising. James Raven’s What is the History of the Book? [Polity, 2018] is astonishing in how much ground it covers, and how accessibly it does so.

INTERVIEWER

Where do you go to get a sense of the wider scholarly conversation in your field?

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

I run a speaker series in textual studies at UW that has been going since the 90s, and our invitees range across periods and languages, so I get exposure to wider conversations that way. MLQ gives me a steady stream of books and articles on literary history and keeps me plugged in to what’s going on in the discipline. I try to go to conferences like MLA and the English Institute every year to listen to papers, and I read PMLA. I quit all social media a few years back so print sources are where my mind is most of the time.

INTERVIEWER

In other of your work apart from Bound to Read you have been drawn to thinking about the broader trends of our field. I’m thinking about your ‘Economies of Scale’ essay, and about two of your current projects: you mentioned another state of the field piece, and you’re also working on a book history companion for Arden. What is the value of these larger conversations threatened at the moment, given the imperatives to publish in haste and to secure a job?

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

I think the situation in the US is different from what it is in the UK. I can’t imagine being able to work, or produce good work, under the kinds of accounting pressures you’re under there. Here there are almost no jobs at all. The only opportunities left for being employed and not thoroughly exploited are ones where you have to be participating in these larger conversations to be legible or viable to a search committee. It used to be that you could count on the people reading your job application to have a degree of period expertise, but now we’re sort of forcibly de-specialising as a discipline so if you’re thinking small or only in dialogue with your advisors then you’re at a disadvantage.

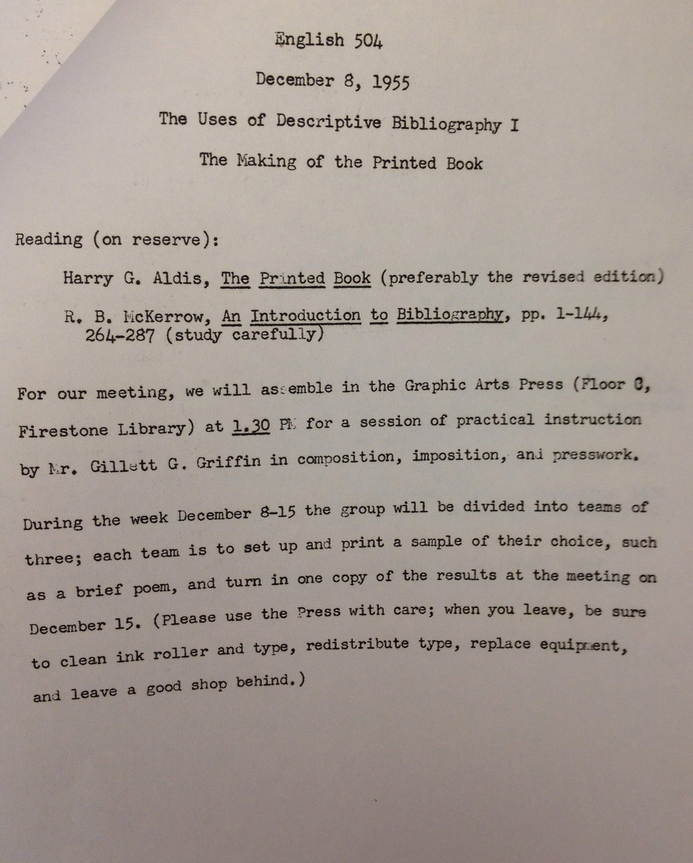

Printing for graduate students in the Princeton English Department from 1955–6. The course was taught by the literary scholar Charles T. Davis, whose archives, including this document, are now in the Beinecke Library at Yale. Image from Jeff of Yale MSS 91, Charles T Davis Papers, box 21, unnumbered folder “Bibliography”.

INTERVIEWER

Courses in book history used to rely on works by Gaskell and McKerrow. Those books remain important but now there are also works by people like yourself and Adam Smyth and Claire Bourne and Zachary Lesser and Adam G. Hooks and so on. How is the field changing?

JEFFREY TODD KNIGHT

The interesting thing about the through line from Gaskell and McKerrow is that you realize book history has always been in the service of institutional stability, at least in literary disciplines. They’re good bookends, actually. In McKerrow’s time, bibliography was the gateway to advanced study because higher ed was expanding, and the field produced the knowledge that built up research libraries and created surrogates for more distributed work.

In Gaskell’s time, bibliography had started its move away from the humanities, but the descriptive arm was in its heyday through the 60s and early 70s because of how it facilitated collecting.

Then the literary disciplines turned hard against institutions. All the people you mention were trained at or just after the moment of high Foucauldianism where nobody wanted to trust, let alone build institutions or invest energy in them. But then social media happened, and Brexit and Trump, and the climate crisis, and liberal democracy teetering on the brink. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the field of book history has been reintegrated in literary disciplines at exactly this time we’ve collectively learned we need to figure out or defend institutions again. In all these surveys about the decline of trust in journalism and law and education, it’s always the library that’s the last institution standing the public graces. That can’t be a coincidence either.

~